The sound designer’s directorial debut feature is one of two Indian films, along with Ritwik Pareek’s Dug Dug, to compete in the Discovery section of the 46th Toronto International Film Festival.

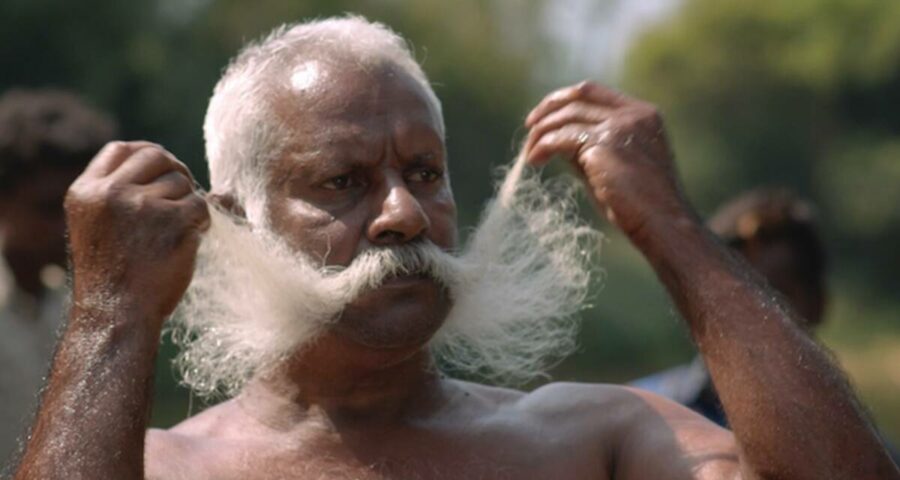

There’s a saying in Malayalam that translates to “kill and dump the body in the river/trenches”. In his debut feature, Nithin Lukose takes this saying and the stories of Kallody’s past (his village in Wayanad), and stews them in a river, which swells with cadavers. At Paka’s centre is a river and a retriever — Viking-like elderly Jose, whose stroking his white mutton chops signals a masculine world order. The gripping film doesn’t have Jallikattu’s high-octane thrill, Paka scores on restrained display and eerie composition.

In this verdant village, star-crossed lovers Johnny (Basil Paulose) and Anna (Vinitha Koshy), from two warring families, hope their love will conquer all, ending the generation-old animosity. But is love all-encompassing, can it conquer bloodied ties? Sounds Romeo and Juliet. Also, Hulchul (2004), the Hindi adaptation of the Malayalam Godfather (1991); that one was a comedy though. This is tragedy, a revenge drama. More Mahabharata than Shakespeare.

Here, Dhritarashtra (Anna’s grandfather Varkey) and Kunti (Johnny’s grandmother) instigate their sons and grandsons, respectively, to avenge the deaths of their forefathers. Will the cycle of violence, patrimony of counterstroke end? Lukose’s directorial debut is headed to the hybrid 46th Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), September 10-18. Paka jostles for spotlight with another Indian film, Ritwik Pareek’s Dug Dug, among 16 films in the “Discovery” competition section, which screens a director’s first or second feature.

The film joins the league of Malayalam films such as Geetu Mohandas’ Moothon and Lijo Jose Pellissery’s Jallikattu that had premiered at TIFF earlier, considered more commercial than other festivals. And perhaps, the right platform for a film like Paka, an indie treatment to a classic, mainstream subject.

Like Don Palathara who dedicates his Malayalam film 1956 Central Travancore to his Achachan’s (grandfather) stories, Paka was born out of Lukose’s grandmother’s stories — of early Christians who migrated from southern Kerala to northern Kerala’s hill ranges in the 1950s, the forested land that the early settlers encroached to cultivate, the struggles they faced, dying of epidemic malaria and fighting wild animals. “Once we are sorted with our fundamentals, we start fighting each other. That’s what we humans do,” says Lukose, 35. The aspect unique to his village — a river in which bodies were dumped — became Paka.

In February 2019, when Lukose went home for the annual St George’s church festival, the idea of a film — peppered with references to the Old Testament — was birthed. Next year, around the same time, he returned to shoot. This January, the NFDC Work-In-Progress project won the Prakash Lab DI Award and Moviebuff Appreciation Award.

The film unfolds a posteriori, we see events happening and hear of what leads to them. The lovers, feuding families are plot devices, fictional fabric woven around the real — the river, an offshoot of Kabini, and Jose, a real-life retriever of bodies from it. “Jose and the river were my first entry point to the story. He’s the only one in this village who can dive into the trenches. There’s another guy, Tiger Johnny, from the next village who can do that too (both feature in Paka),” says Lukose, who saw and heard many tales from his police officer father while growing up.

Kocheppan’s (Jose Kizhakkan) track is inspired from real life, from the recent past. A man in Lukose’s village killed five members of a family, served a jail term of 12-13 years. He returned, to be killed by that family. If Kocheppan is Goliath, his non-confrontational nephew Johnny (Paulose) evolves as a “new” Undertaker — an auteurial wink at Lukose’s younger WWE wrestling-consuming self, when Undertaker was a cult.

In this male universe, the female — grandma or river — seeks blood. The rock opening to the river is a symbolic vagina. Blood will be flown, in a world that knows destruction, not creation. We only hear the quivering octogenarian matriarch, a key character, played by Lukose’s own grandma, and see her photo after her end — “her face was shown in earlier edits”. A creative input by co-producer Anurag Kashyap, who boarded the ship in post-production. Kashyap, whose Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) was another story of family feuds and cycle of vengeance, had told Lukose, “if you show a monster, she will be less of a monster.”

The other producer, Raj Rachakonda, had worked with Lukose who did the sound for his Telugu film Mallesham (2019). The FTII-graduate has been the sound designer on films like Raam Reddy’s Thithi (2015) and Dibakar Banerjee’s Sandeep Aur Pinky Faraar (2021), and won the first Resul Pookutty IIFA Foundation scholarship award in 2010. He interned with his FTII-senior and Oscar-winner Pookutty (Slumdog Millionaire, 2009), who “asked him to first sort all the hard drives (about 100) at his studio, for a month”.

For his own film, Lukose handed over the reins of sound to another. He’d pre-recorded the sounds of the place — the festival, river, monsoon — and returned later to shoot with this bank. He gathered a mixed bag of known actors, his friends and local villagers, and had to tone down the melodrama the villagers were capable of. While times change, “the Communist Party that was banned in Kerala in 1956 is now the government,” says Lukose, some things don’t — “the Taliban has returned to Afghanistan. People will fight forever.” Like the cyclicity of the film’s universe. Varkey’s grandson sits in the absent-patriarch’s chair, a boy is born in the house, there will be no end to it. In Paka, an elderly man sits across the river, witnessing everything, as he listens to the radio (Colombian football commentary, war news, shooting at the border) — his only connect with the world outside the fictional one. Johnny’s dead uncle and brother join him. Maybe he’s the grandmother’s dead husband who was a trumpet player, maybe he’s God who sits and laughs at human folly. In the end, the village is a microcosm of the world — with all its fissures and follies intact.

Source: Read Full Article