‘Of the people here in Europe who have watched The Story of Film: A New Generation, the most talked-about clip is the one from Ram Leela.’

Mark Cousins is a walking, talking, thinking encyclopedia of cinema.

His 15-hour long documentary The Story of Film: An Odyssey (2011) — based on his book by the same name — is considered a landmark piece of work and has played at numerous film festivals. It is now shown to film students in various countries.

For the film, Cousins travelled to India where he interviewed film personalities like Amitabh Bachchan, Javed Akhtar, Sharmila Tagore and Mani Kaul.

The chair of the Belfast Film Festival, Cousins has also directed a 14-hour documentary Women Make Film. The film’s narrators include Jane Fonda, Tilda Swinton and Sharmila Tagore.

After having made a range of other documentaries, including one on Orson Welles, Cousins is back with two new films, both of which were recently premiered at the Cannes film festival.

The Story of Film: A New Generation is a sequel to his 2011 opus.

Here, Cousins covers films made between 2010 and 2020, exploring a range for world cinema, but also how we watch films.

He covers nearly 90 films in the documentary from Joker to Mad Max: Fury Road, Parasite and the Thai master Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Cemetery of Splendour.

He also pays tribute to a few Hindi films of this decade like PK, Gangs of Wasseypur, the documentary Reason, Ship of Theseus and Goliyon Ki Raasleela: Ram Leela.

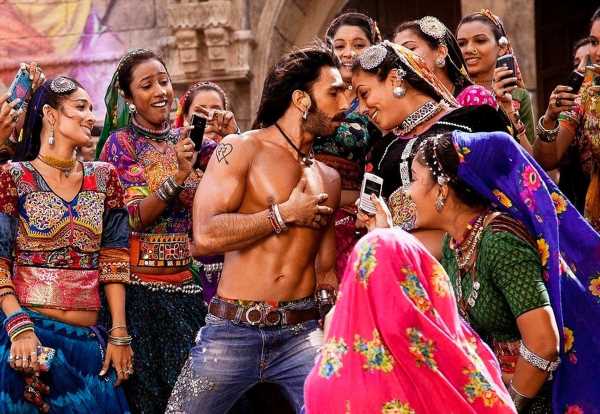

In the documentary, he refers to the Tattad Tattad song with Ranveer Singh from Ram Leela as the most choreographed film sequence or the dandruff song.

In his second film, The Storms of Jeremy Thomas, Cousins joins the legendary British producer (The Last Emperor, Crash, Sexy Beast) on a road trip from London to Cannes andexplores his life and career.

Mark Cousins tells long-time Rediff.com contributor Aseem Chhabra: “I want to surprise you as a member of the audience.”

Mark, first of all, congratulations. You have two films playing at the Cannes, which is really remarkable.

I know, it was quite a surprise, but I am really pleased.

The lockdown for me was a time of fertility and activity. I got a lot of work made, hence the two films.

The first The Story of Film: An Odyssey came out of a book you wrote.

Right. I wrote the book 12 or 13 years ago and then my producer John Archer said why don’t try and make a film?

For that, we travelled the world.

I interviewed people like Amitabh Bachchan and others in India.

But with The Story of Film: A New Generation, you worked on the script all by yourself. What was the process like? Did you re-watch a lot of films?

Because of the lockdown, it was an opportunity to plug the gaps in my knowledge.

I had seen lots of films, but I had also missed many films because I am a full-time film-maker. So that was the opportunity.

I had seen all the Indian films I talk about, but I hadn’t seen many from other countries. So I watched a lot. And I liked the process of structuring the story.

While you were working on the themes and the chapters, the clips you chose, were those all from your memory?

I have a good visual memory, not a great word memory.

So when I watch a film like Gangs of Wasseypur, I remember the key moments that really stand out for me.

I was looking for standalone moments, which you can take out of the context of a film and set it in a new film, and they will still be interesting to the audience, without too much explanation.

I seem to collect them in my brain.

But I also keep a notebook.

I remember when I saw Ship of Theseus for the first time, I thought wow, that’s trying to say something about identity and its complexity.

So when I realised I had a section in The Story of Film about identity, who are we, what have we been digging for, I knew Ship of Theseus had to be in there.

Right at the beginning, you start with a clip from Joker and then move to Frozen, to Baby Driver and then PK.

Of course, you logically explain it, but how does that transition, that jump between different genres of films happen?

How does your brain work?

(Laughs) I think it is important for me and for many of us to be blind to the distinction between high and low art, or experimental and mainstream film.

If you love film, then you will ignore these categories and see all the films, if possible, on a level playing field, where what matters is their innovations and their themes.

Joker is an adult film while Frozen is very child-like. Not many people would think of them in the same breath.

But actually, I think a spark does fly between Joker and Frozen when you put them together because the common theme is the idea of people who feel overlooked and are unseen.

I love making those connections.

I also want to surprise you as a member of the audience.

To begin a film with Joker and then Frozen is to try and grab your attention, plunge at the deep end.

I am sure the process of getting permission to show the clips must be very complicated.

It’s not complicated, to be honest.

We worked with the fair use legal precedent which means you are allowed to use an extract of artwork without asking for permission from the owner.

So it is a relatively simple process. A lawyer approves it all, but we do not have to ask for permission.

I want to understand your passion for world cinema. How and when did it start and when did you discover Indian cinema?

My passion for world cinema started when I first saw French films, but those were still close to my culture.

About 30 years ago, I got seriously interested in cinema from other cultures, opening my eyes.

The first country I really fell for, as far as cinema was concerned, was Iran.

I went to Iran after seeing its cinema.

That combination of using cinema as an imaginary step into that country and then going there was crucial.

As far as India is concerned, in 2001, my partner and I drove from Scotland to India.

It was five months driving and six weeks in India. We saw lots of India.

I had seen the famous art films and the parallel cinema of India.

I had seen some Hindi films, but going to India overland, arriving in Mumbai and driving along the west coast, going to Pune, Ajanta, I fell in love with the country.

Cinema makes you fall in love with a country. Then going there makes you fall back in love with its cinema.

I have continued over the years to inform myself about Indian cinema.

I don’t claim to be an expert in any way.

I know it is a massive multiverse, like a spider-verse.

Then a few friendships helped.

I got to know Nasreen Munni Kabir in the UK and she took me to see Aamir Khan. And then we brought him to Belfast. And so my enthusiasm for Indian cinema deepened.

It’s very interesting how you introduce some of the clips, for instance, that dance scene from Ram Leela with the dandruff song.

It’s very popular in India, but I don’t know what percentage of your audience in Europe would know this song. You really want to show them stuff they would not have seen.

Of the people here in Europe who have watched The Story of Film: A New Generation, the most talked-about clip is the one from Ram Leela.

Unfortunately, as you know, movie lovers in Europe and America, unless they have Indian heritage, are not informed about Indian cinema.

That is why I put it in some context, mentioned the choreography and dance from Magic Mike, male body and all these things.

I want to suggest to people that maybe some of the best things in cinema are happening in India.

How does your narration evolve? Are you trying to be a critic or an educationalist or a friend sitting next to us and recommending films?

Yes, the third of those. I never review films so I don’t feel like a critic.

I don’t think I am an educationalist even though I am very pleased when my films are used in film schools, around the world in Beijing, New York, and other places.

The main purpose isn’t to educate or evaluate. It is precisely as you said.

Imagine we are sitting in the dark and I am sitting very close to you and that’s why I talk quite gently in my narrations in order to bring intimacy, a nighttime atmosphere.

I am very interested in the idea that films can almost hypnotise you in some way.

It’s easy to be boring, but if you go gently and slowly, people can get slightly entranced and that’s what I hope happens.

Many people at Cannes have said that it’s a long film, but it could have been longer. That’s nice of them to say.

You may have also noticed that I write and speak in the present tense. I don’t say he or she did that. Rather I say, he or she is doing that.

A word I use a lot is ‘this’ and that means you and I are watching together in the present tense, seeing the clip unfold in front of us.

And I don’t use full sentences. Instead, I use partial sentences to try and declutter the voiceover a little bit.

That’s really interesting. You speak with a mesmerising tone, almost like you are whispering in our ears and making us notice some points on the screen that we may have missed.

I am a big fan of the great Soviet film-maker Sergei Eisenstein. He started in theatre.

His teacher once said to him your job as theatre director is to move the audience’s eyes around the stage.

I feel slightly similar in my work.

I want to move your eyes around the screen when we are watching a film together.

How do you collaborate with your editor Timo Langer? What’s that process like?

I write what we call a paper edit, which is a very detailed script. And I indicate the points that should come into and out of a clip.

Because of COVID, we were working at a distance.

I would send him that paper edit, which was a long document of 150-200 pages.

Plus, I would send him my recorded voice over.

My producer would send him blu-rays of all the films. So he got a detailed description.

He would assemble the first 20 minutes of the film, we would look at it and make the changes.

Because we work with a low budget, we don’t spend ages on the edit.

Some film-makers typically spend a year on the edit looking for the structure. We have the structure upfront.

I would say between assembly and the final cut, we would change less than five per cent, moving a few things around and deleting a few other things.

Timo and I have worked together on 14 features and 30 plus shorts. So we work well together.

The second film about Jeremy Thomas is so charming. Had you driven with him to Cannes before?

I hadn’t travelled with him.

I had known him a bit and I admired him, seen him at some parties.

No, we hadn’t done a road trip together. I didn’t know he drives super-fast.

I was asked to make a film about Jeremy.

In a conventional way, we could have interviewed so many directors like David Cronenberg, Stephen Frears and all the other great film-makers Jeremy worked with. But I felt it should be very focused on the car, the trip.

The only way we would escape the car and the trip would be by adding film clips. We didn’t have any drone shots.

Usually, in a film like this, you will have a second car following that would take shots from outside, looking in. But we didn’t do that either because that would have taken us out of the car.

The aim was to do ‘a two people in the car film’. A Thelma and Louise type of film.

Were you handling the camera or there was a cameraman at the back?

There was no crew.

I did a camera and sound.

I had two tripods, a bunch of batteries and a sound recorder. At times it can be tiring. But it was worth it.

I learned a lot from Abbas Kiarostami and the other Iranian film-makers.

Keep it simple.

Keep the technology as small as possible. And then you get the kind of intimacy you are looking for.

And you knew you only had five days to make the film?

It took five days to Cannes and then we filmed for a few more days.

We would film a lot on the road.

At night, we would have a glass of wine and I would put on the sound recorder and we would talk some more. That’s why most of what he says is in the audio-only. We don’t see him talking to the camera.

It liberated the visuals and during the editing, we felt free to add in clips of so many different films.

He has produced African, American, British and Japanese films.

That’s a feeling of kaleidoscope in our heads. As movie lovers we are walking, talking kaleidoscopes.

You did show a clip of Bernardo Bertolucci and another one of Nicolas Roeg. But Jeremy doesn’t talk about Bertolucci. He talks about the films he produced for him. You didn’t want him to talk about Stephen Frears for instance?

No, I wanted it to be Jeremy’s idea.

He has worked with so many great directors and I could have asked him what was it like to work with them or how he prepared the films? That would have been very interesting.

But I wanted to make a film about a producer as an auteur. His ideas, his themes, his take of the world, his contradictions.

I wanted to portray this gentleman with a fiery imagination. So that is why I didn’t talk to him about his famous collaborators.

What is next for you?

I made three films during the lockdown.

The third is The Story of Looking. It’s an adaptation of my last book. It’s about our visual lives.

During the making of it, I had a major eye operation and we filmed that in 4K and it’s the centrepiece of the film.

I hope your eyes are okay now.

Yes, they are much better than before.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article