‘For him to suddenly leave the way that he did, it shattered me.’

‘It took me a long, long, time to come to terms with it.’

‘Because the loss of such a friend can destroy you.’

‘The loss was and continues to be immense.’

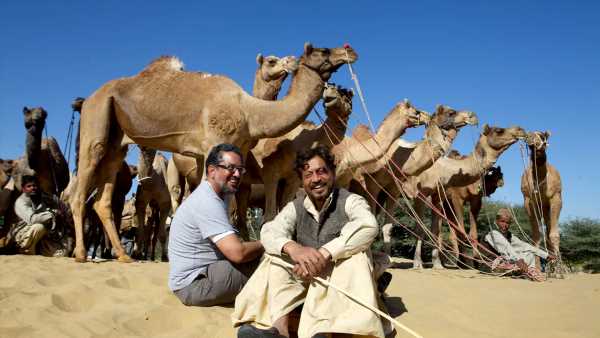

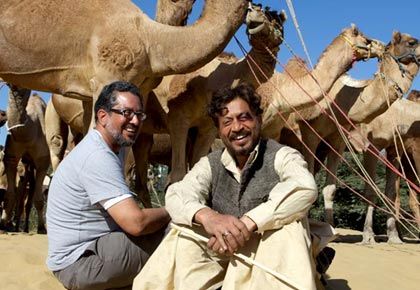

Geneva-based film-maker Anup Singh directed the late actor Irrfan Khan in two acclaimed films, Qissa: The Tale of a Lonely Ghost (2013) and The Song of Scorpions.

During the course of the making of these films, they developed a deep friendship that lasted until Irrfan passed away on April 29, 2020.

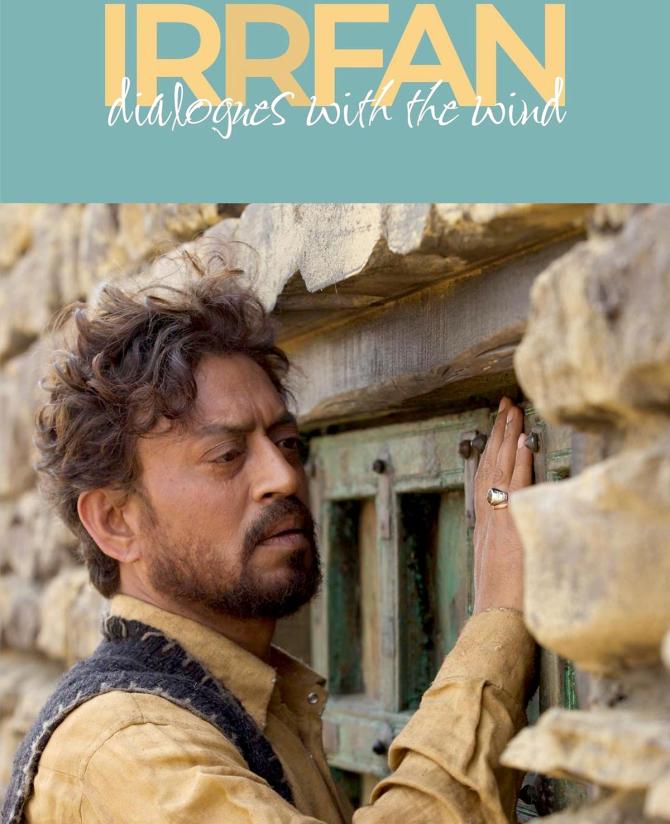

In remembrance of his dear friend, Singh wrote Irrfan: Dialouges With The Wind, which helped him to cope with the sudden loss.

The Song of Scorpions releases in cinemas for the first time on April 28, after its festival premiere in 2017, and makes the director reminisce about Irrfan.

“We could have made films together till the age of 90,” Anup Singh tells Mayur Sanap/Rediff.com.

The Song of Scorpions is finally releasing a day before Irrfan’s third death anniversary. We are going to see him on the big screen for the last time. What’s going through your mind?

As the director of the film, I’m overjoyed that the film is releasing.

But again, I am in grief that Irrfan is not with us.

It is such a bittersweet moment.

There are moments that would fill me with tremendous sadness. I see the generous response with which the audience is reacting to, for example, the announcement that the film is going to be released.

For Irrfan, I’m sure this would have been a moment of immense joy.

So, really, I’m very happy, but also deeply sad.

As his director and as a friend, what amazed you most about Irrfan?

One of the main things about Irrfan was his immense curiosity about everything.

There is nothing that he felt that he understood, or he knew.

He never felt that he knew anything beyond a certain point. There was always more that he felt he needed to find and seek.

If we were walking around, it wouldn’t be very surprising if he would pick up a little pebble from the road. And because it had, let’s say, a yellow or a green or a blue streak in it, he would then wonder what kind of minerals the pebble has.

Then he would ask, why is it circular? How did it become like this?

He would think about how this pebble must have travelled from God knows where, to finally be here in our paths.

And before he picked it up, how many, maybe thousands of other people might have picked it up before him in there?

So the stone really was full of the history of human civilisation and the history of nature. And of course, Irrfan’s own imagining of the various stories that this stone carried with itself.

One of our deep connections to each other was that within cinema. We always wanted to grow because none of us felt that we knew enough.

He never felt he was a master of acting. And I’ve never felt that I’m a master of film-making.

Every moment, every film, is a great opportunity to grow.

What we could do with each other, and I think that is why we related to each other so closely, and so passionately, is because we could encourage each other to go beyond every moment of a scene.

We would push each other to go further and what helped was not simply the pushing, but both of us knowing that we were safe with each other.

We would never have any kind of stupid argument. But we would always have questions.

Let’s look more.

Let’s see more.

Let’s taste more.

Let’s try more.

That was a real partnership, encouraging each other to go further and further.

The book is a beautiful collection of your memories with the actor. Did writing it help you to cope with his loss?

In many ways, yes, it did.

When you’re working together on a film, the person is right there in front of you. So, you’re working face-to-face.

You can touch the person. You can make the person turn. You can make the person come towards you. You can look at the person, the person can look at you.

it is very concrete, it is very palpable.

However, while writing the book, it was memories.

While memories can be very powerful, and you can feel that the person is around you, there is a lack of immediate reaction. (Laughs)

The immediate way Irrfan might look at me because I’ve written a certain kind of line. That is no longer possible.

So yes, I did come to terms with his passing away. But it was also very paradoxical.

Because I realised that he was not going to be any more in any more of my films. I was, in fact, inspired to write film scripts with him in my mind.

In fact, I’ve written three film scripts, after his passing away, with Irrfan in them.

That was my way of continuing my work with him because whatever I wrote, I could imagine him doing it in this way, or not doing it in this way.

For a long time, just writing the scripts kept him alive for me.

Then I could finally let him go, when I realised that now these scripts will forever go into some dark corner. And we will never make them into actual films.

That was my process of coming to terms with losing him.

Everyone has a different Irrfan for them. From millions of fans to people who worked with him, everybody adored him. What you knew about Irrfan that others did not?

It was one of the greatness of Irrfan that because he did not feel that he was a master of anything and he always wanted to grow. He used to look for a new way of talking to people.

He wanted them to share their life, deepest beliefs and aspirations with him.

One can have an ordinary conversation and it doesn’t go anywhere.

Irrfan really hated those kinds of conversations.

What he wanted was to find for each person, that language, which would encourage them to trust him and to share with him their living on this world, just the way he was ready to share with them.

What I saw in him was a man completely dedicated to the idea of growing.

He really felt that in this world, the more we open ourselves, the more we will be able to speak to other people.

That we will not be caught up in some communities or little groups or a small idea of belonging here or belonging there. We would actually be able to belong to the whole world.

You were born in Tanzania and came to India at the age of 14. How did your fascination for the hinterlands of India grow where most of your films are based?

Every kind of terrain is very, very, important. The sea was very important in my childhood.

When I came to Mumbai, the sea was all around, but it wasn’t the same sea at all. Here, the sea was very different from my experience of the sea in Tanzania.

Therefore, I had to learn again, how to live in different kinds of geography.

Any kind of terrain, any kind of land, and any kind of location either makes you feel at home or it makes you feel homeless.

It either shows you ways of living in it or you never learn how to live in it.

My journeys into different parts of India were also journeys into trying to understand where is that terrain where I would feel at home.

Therefore, I travelled practically everywhere in India, and spent months and months in different kinds of places.

Slowly, I realised that every terrain changes you. It gives you a different view of the world as well as yourself.

Coming to the films that I make, well, they are really about refugees. All my films are about refugees, in some way or the other.

As my teacher Ritwik Ghatak used to ask, ‘Who is there on this earth who is not a refugee?’

In a sense, we are all refugees.

My very first film, which was in Bengali, called The Name of a River (2003), was about refugees, set in the Partition era.

Qissa is about refugees, again, set during the Partition.

The people in The Song of Scorpions are nomads. They don’t belong to any one place.

When we went to these different locations, Irrfan and I would spend hours just sitting in the space where we were going to shoot.

We would walk around, and try to understand it.

We would talk to people, who lived there and learnt from them.

How did the idea of casting Golshifteh Farahani come about? I think I read somewhere that it was Irrfan who suggested her name to you.

Irrfan and I were at some international film festival where Qissa was being screened. Through the crowd, we saw this really gorgeous woman walking towards us. And she came to us and said: ‘Coffee?’

Of course, you can’t say no to Golshifteh Farahani!

She took us for coffee, and that is how we met her.

For the next two days, during the festival, we spent practically every minute together.

We would meet at breakfast, watch films in the breaks, talk about our lives…

There was one thing that really struck me about Golshifteh. She lives in exile from Iran. She cannot go back to Iran.

When she spoke about that exile, she strangely never spoke about it bitterly.

She spoke about how the exile had actually opened her to the possibilities in herself.

I think that is what makes this incredible actress what she is.

The character in The Song of Scorpions, Nooran, is also, in many ways, a woman who has been exiled from her village, her body, and her home.

The more we spoke to her, the more Irrfan and I felt that there was something about her that was very much in the spirit of the film that we were going to do.

Then, after two days, when she was leaving, she came to say goodbye.

Irrfan kept looking at me, and there was a kind of desperation about him, as though he wanted me to say something. But I ignored him.

When Golshifteh had gone away, he turned to me agitated and said, ‘Anupsaab, she is our actress for the film, you should speak to her.’

I took out my phone and showed him that I had her phone number and that Golshifteh and I have already made plans to meet in Paris to talk about the film. That is how we cast her.

Apart from Irrfan and Golshifteh, the film also has Waheeda Rehman and Tillotama Shome. How did you assemble this dream cast?

Waheedaji had seen Qissa and she liked it very much.

When I was writing The Song of Scorpions, the role of the grandmother was pivotal to the script.

I went to Waheedaji and she said, ‘Look, I have not taken any film for the last seven or eight years. I’ve retired and I’m very happy as I am. I don’t want to do any more films.’

I said to her ‘Let me just tell you a little about what the role is.’

She was very kind and agreed to hear the story.

I said this is about a woman living in the desert. She is such a great singer that when she sings, the desert begins to blossom.

That is all that I said to her.

You could immediately see this sparkle in her eyes.

She said, ‘What? I’m a singer in this film!’

Then she said, ‘Can I sing my own songs in the film?’

That was her question, and my secret desire.

I said, ‘Waheedaji I would really like you to sing the songs in your own voice.’

So for the first time in her career, Waheedaji is actually singing one of the most important songs in her own voice in this film.

With Tillotama, it was very different.

I was ashamed to ask her to do this role because it is so tiny.

We had worked together on Qissa and became very close. I felt that the friendship that we had developed would bring a wonderful spirit to the film.

I requested her to do this really minuscule role. And she agreed.

It really felt like the beginning of a great creative collaboration between Irrfan and you. Very unfortunate that it ended abruptly.

Yes, absolutely.

We spoke about so many films that we wanted to do together.

If you look at all the ideas that I’ve jotted down and some of the scripts that are written, I think we could have made films together till the age of 90.

For him to suddenly leave the way that he did, it shattered me.

It took me a long, long, time to come to terms with it, not only personally but also in terms of my imagination. Because the loss of such a friend can destroy you.

The loss was and continues to be immense.

Source: Read Full Article