Dear Friend is for those who idealised Dil Chahta Hai all out of proportion, and then warmed up to the premise that friendship could be a lot more complicated, and transient, observes Sreehari Nair.

Vineet Kumar’s Dear Friend subverts at once two very firm cinematic traditions: The buddy flicks we tend to get high on; and the man-who-came-into-my-life-and-changed-my-life set of movies that persuade us to look for divine figures among smelly mortals.

Dear Friend is for those who idealised Dil Chahta Hai all out of proportion, and then warmed up to the premise that friendship could be a lot more complicated, and transient.

It’s also for those who walked out of mush-fests like Anand, Bawarchi and 3 Idiots only to realise that the ones who change your life aren’t necessarily those who keep their promises or teach you to love yourself, they are often times the ones who find all kinds of innovative ways to break and remake your heart.

The movie takes swings at so many cuddly themes in the course of its running time that its makers could not come up with a suitable spiel to market it to the mass audience. And after an indifferent show at the theatres, Dear Friend is now out on Netflix, where you can watch it encased in your personal bubble, while noting that the ironies begin right at the title.

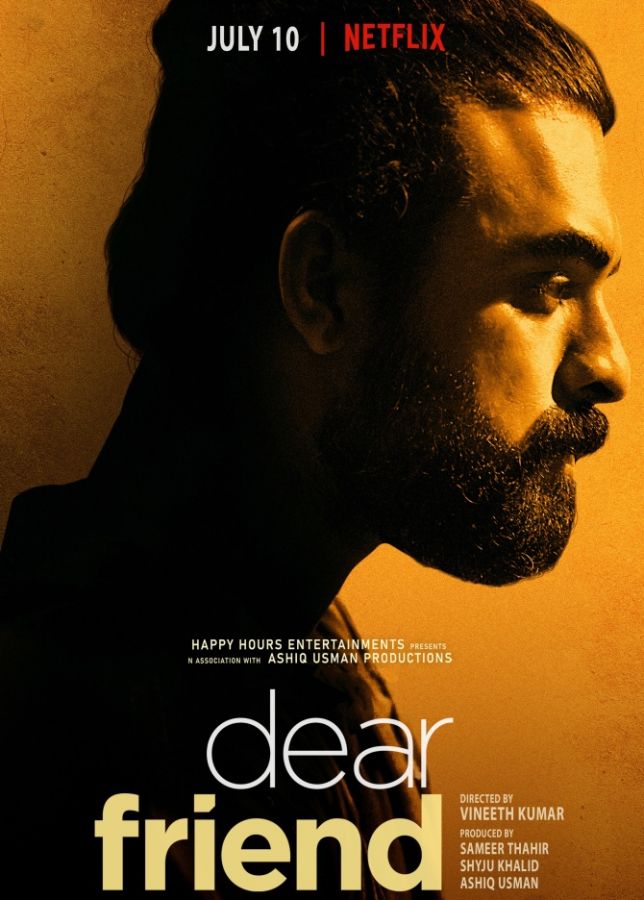

Tovino Thomas plays Vinod, who charms the pants off a quintet living in the Bangalore of low-rise buildings and leafy streets, who disappears one fine day without any intimation, who is revealed by and by to be an indiscriminate conman, and who resurfaces at the climax as some sort of a realist hustler — a hustler who when confronted owns up to his peccadilloes while correcting a few emotional outbursts.

As Vinod’s friends — who up until the climax carry with them some or other strand of ‘connection’ they had forged with this punk of a man — take leave of him, we identify with their dejections, and with the insights they gingerly arrive at.

We think back to the revelries, Vinod’s numerous acts of kindness, the earnest conversations, and we come to understand that all through those charming moments the five softies were dealing with someone a lot shrewder than they and made of tougher clay.

The softies may have sentimentally believed that they had knitted a comfy private circle of six, but Vinod, it dawns on us, was as much ‘outside’ that circle as he was in.

His edgy, jocular smile then comes back to haunt our idyllic visions of the world.

Director Vineet Kumar and Arjun Lal (who has supplied the basic story idea), had both made it as child actors, and they have, with this film, got together to craft what can be safely called Indian Cinema’s first coming-of-age tale for grownups.

The screenplay, developed by Sharafu and Suhas, isn’t out to infantilise you, and with not more than a few snapshots you are handed out an almost clear-eyed evocation of the dynamics the six friends share.

We catch them as they are about to move from a phase of wanting to exhibit their friendship to the world to nurturing small annoyances for one another.

Somebody is always stepping on somebody else’s toes. Perspectives don’t always jive.

Plans for enjoyment as well as professional plans (the four guys are struggling to bring a health app to the market) don’t come to smooth fruition. Irritations are bandied about over cigarettes randomly lit.

In one of the scenes, we see two guys from the group casually bitching about a third one, Sajith (Who else but Basil Joseph?).

Sajith, a software coder by vocation, cannot help but transform into a social peacock by night — and for the other less ostentatious birds, this is starting to be a vexing makeover to deal with.

There’s always one like Sajith in every group of techie bachelors holed up together: He is typically the guy who wouldn’t mind stripping down to his underpants as you are watching, and who tries to offset his lowly beginnings by sounding the loudest wolf-whistles at parties and overdoing the alcoholic stimulation business.

If this were a conventional film, a character like Sajith would have been endowed with the film’s best zingers. But it’s a sign of how mature the writing in Dear Friend is that the back-and-forths here are mostly prattlings and aimless palavers, all waiting to be juiced up by the actors’ special enunciations and gestures.

This is one of the many ways that screenwriting in Malayalam Cinema has evolved since the Syam Pushkaran Consummation.

Back in the 1990s and 2000s, the acidic Malayali tongue would take over a Malayalam film, and turn it into a series of neat setup-and-punchline routines (The much beloved custom of ‘Counter-Adi‘ had gone from being witty to cranky to plain silly).

Syam Pushkaran was the one who demonstrated that mere brightness in writing may be enough for copywriters, but real writers must strive for more: They should also scratch at something unresolved in their characters, fondle bruises left open, give the little asides and guileless repetitions their rightful due.

Sharafu and Suhas respect the silences between sentences that hang over the living rooms and cubicles in this movie like a festering fever. And working with Director Vineet Kumar, the screenwriting duo make sure that every time the six characters are together, the energy of the scene is distributed evenly among the principals, albeit without making the endeavour seem like a mathematical thing.

Urban dramas about young people are apt to giving you characters whose mannerisms you can unconsciously applaud, and even ape.

In this movie, there’s nobody to wink out his sarcastic notes, or walk like a ‘cool cat.’

As a matter of fact, we have Arjun Radhakrishnan here, whose Shyam walks as though to endorse his slowly graying temples.

And yet, what screen presence!

When Basil Joseph’s Sajith, the laboring hedonist, throws up after a session of binge drinking, Shyam, who’s clearly running out of time and patience, utters a sharp dialogue in passing, and gobbles up the moment.

In a sequence which has the police questioning his dealings with Vinod, Shyam’s perfect stillness becomes his defense.

These are original creations, not a degree wiser or more resourceful than the people we meet in real life, and there’s a hint of pop-culture having modified their bodies and shaped their characters.

Sanchana Natarajan, who plays Amutha, the lone Tamilian in the otherwise all-Malayali group, has supple lips that seem plucked out of fashion magazines (they are lips that Andy Warhol would have dug), and when there’s a need to act flirtatious on the fly, Amutha saunters barefoot with her sandals clutched in her hand.

The girls are constantly battling demands for propriety, and the complications that arise out of such tensions have their own allure.

Darshana Rajendran’s Jannat, a practicing psychiatrist, sneaks out of her hostel for a night-out with the guys, misses her father’s call, dials his number, and fibs about being in the bathroom.

When Jannat reaches her hostel premises the next morning, she finds her father waiting outside: It’s the great Jaffer Idukki — he catches her fib, and proceeds to deliver the most painful line in the film.

Jaffer’s is a two-scene character, a man who reserves his brightest smile for those occasions when he feels most let down.

The father-daughter bond is suggestive of a higher aesthetic that overlies Dear Friend: Almost all the relationships in the film are working their way through stoppages and breakdowns.

There’s, for instance, Jannat’s relationship with her Hindu boyfriend, which has to contend with more than just the lovers’ differing religious backgrounds: it’s a relationship of two people who are frequently causing each other to miss elevators or revise schedules.

Life that changes on a dime is Dear Friend‘s guiding beat; and the film’s technique is revved up to capture this beat.

In a sequence that gradually approaches a dream-like perfection, we see the friends gathered in their hall-room, and Tovino’s Vinod ambles in holding a puppy he has rescued from the street.

Vinod thrusts the puppy in Jannat’s face, even as she squirms and recoils in fear, and the motionless-camera-and-wide-shot approach suddenly steers into roving, handheld photography mode.

It’s a Shyju Khalid special, that whole sequence, and I could not help but wonder if there’s another cinematographer in India who can achieve beauty with such unassuming ease.

While it’s practically impossible to hate a movie character who is in the habit of making small talk with a puppy, Tovino’s Vinod does, by the end of Dear Friend, manage to complicate our responses.

Come to think of it, Vinod’s reaction to the five friends’ wholesale admiration of him mirrors Tovino Thomas’s reaction to stardom.

For in a cinema culture that thrives on getting its stars trapped in prefabricated images, Tovino is the star who doesn’t stay still; he’s the star who will flout all rules, who just wouldn’t behave.

Amutha with her Andy Warhol lips wants to marry Vinod; one of the guys wants Vinod to have his sister; Jannat with her psychiatric mumbo-jumbo wishes for him someone almost otherworldly — they all want the moon for him, but Vinod is a man of the earth.

When Basil’s Sajith pukes his guts out, only Vinod empathises with his condition: With his broad hands he scrubs the ogre clean, while ensuring that his demeanor never strays from that of a no-nonsense charwoman.

This scene is the closest we get to knowing Vinod — he is the angel with an alternate side.

A flashback shows him taking care of a friend’s cancer-stricken mother; and later, he adds this mother to his own biography.

What does this make him? A self-appointed collector of the debts the world owes him? An honest fake? Someone who drives his cart and plows over the bones of the dead?

It’s instructive to know that while the five friends are getting their first taste of metro life with all its freedom and colour and neon nights, Vinod, who has also spent significant amounts of time in Mumbai and Kolkata, knows the dark side of big cities.

He has firsthand knowledge of the dirty alleyways and the sunken damaged hearts that hide behind the speed and the glitter. And yet, the man is essentially rootless: He takes something from every neighborhood he has been in, refurbishes himself, and keeps going.

The life-changing angel trope that we are served at the movies is just that — a trope.

Sharafu and Suhas expose the lie in the trope by making Vinod one hell of a cipher, but they also have the good sense to make him a cipher imbued with life force.

It would be a fair judgment to say that Dear Friend does turn flabby in the Mumbai section of the story.

When the friends go searching for Vinod’s past, they kind of lose their individuality, their obsessions congeal into one, and there are other details that irk.

In a flashback scene we see Vinod, who is shown to be living in a Slum Rehabilitation block, telling his mother that he has booked a flat in Juhu (Juhu!!!), and the mother readily believes him.

I don’t know if there’s any Mumbai-based mother so docile as to believe a claim that grand — even if coming from her own flesh and blood.

That glitch almost made me question the film’s Bangalore portions, if they too were constructed on similar fallacies in detailing.

But the undercooked Mumbai section could not possibly have led to the empty movie halls that greeted Dear Friend during its theatrical run.

Promoting a movie that prides itself on being a revisionist version of genres much adored, is an understandably difficult proposition; and in the case of this one, the word-of-mouth never caught on, what with the reviews and their liberal usage of such dead phrases as ‘intriguing’ and ‘slow burn’ (Phrases that have come to mean ‘stay away!’).

The truth is that most people who loved Dear Friend have had a difficult time talking it up, for it defies easy descriptions.

If only this were a movie that celebrated friendship, or, alternately, if it were a cautionary tale, there would have been some leeway. But as matters stand now, it’s a movie that chases after an itch, a feeling of pleasure-pain, and winds up showing us how beautifully fragile friendship can be.

It’s also a movie that evokes the wisdom of youth in the most innocuous of sequences — such as when Vinod declares that he’ll serve “only one baby piece” of the marijuana cake he has personally baked.

What it isn’t, thankfully, is a movie that pushes self-help tips at you; and every time the mood becomes a tad too cloying, Dear Friend smartly undercuts its own enthusiasm.

There’s a scene of Vinod and Jannat listening to a song that describes life as ‘a bittersweet dish that one is obliged to relish bit by bit’, and just as you begin to dread that something sickeningly syrupy is perhaps brewing round the corner, the song is revealed to be a jingle for a life insurance company.

Outside of such diegetic examples, the music is wonderfully dopey.

I particularly loved the transition from soft guitar strums to slow drum rolls, in a scene of the friends trying to freefall into a mattress after the marijuana cake has begun to take effect.

Justin Varghese’s talent is used judiciously here (that’s what makes it twinkle), and most of the scenes attain a sense of musicality even without a background score.

Keep an eye out for a fleeting scene in which Amutha tosses a Tamil name at Vinod, who plays around with the name for some time, and then with a mock-growl assigns it to his puppy: there’s music in the spit-filled rhythms of speech there.

It may interest you to know that when Vinod disappears from his friends’ lives, he leaves his puppy behind; so that the animal’s ever-swelling presence becomes a living symbol of its master’s betrayal.

And yet, if you think about it, the casualties of Vinod’s exit are hardly material; what he actually betrays are those conventions of popular movies that soften our brains beyond what’s healthy.

Dear Friend begins with a play on Tovino Thomas’ character in Minnal Murali, last year’s big hit, and immensely enjoyable superhero fare.

The opening scene, here, has Vinod being forced into a Superman outfit, despite his obvious reluctance to wear it, and then paraded through the streets of Bangalore. And if the plot of any superhero movie is invariably about its hero facing up to his responsibilities, Vinod’s fate is to shun his outfit, turn his back on his fans, and leave them in a lurch.

Yes, the real betrayal in Dear Friend is that the reluctant Superman of this movie emerges from his den declaring categorically, ‘Leave me alone, I am just Clark Kent!’

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article