Just as much as the magic of cinema, Chhello Show is about the imagination of a child and the typical Indian jugaad, observes Deepa Gahlot.

Pan Nalin’s Gujarati film, Chhello Show (English title: The Last Picture Show) has got an inordinate amount of attention because of its status as India’s entry to the Oscars, beating crowd favourite RRR.

It has made the rounds of film festivals and comes with appreciative reviews, mainly because it does evoke nostalgia and also captures the colours and sounds of a Gujarat village before they are irrevocably altered.

The obvious inspiration is Cinema Paradiso, Guiseppe Tornatore’s classic, love letter to cinema, but Nalin expresses ‘Gratitude for illuminating the path…’ and lists the great masters, the Lumière brothers, Eadweard Muybridge, David Lean, Stanley Kubrick and Andrei Tarkovsky.

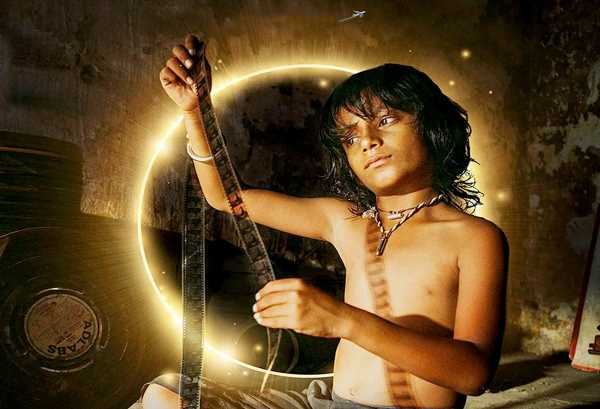

Samay (Bhavin Rabari) is a bright eyed little boy, son of a tea seller (Dipen Raval) at a tiny village railway station.

The father believes films are evil and no good Brahmin should watch them but he does take his family to watch a religious film, Karishma Kaali Ka, in the decripit Galaxy cinema in a nearby town.

Samay is bewitched!

He starts bunking school to sneak into the theatre.

When he is caught and chucked out, he bribes the protectionist Fazal (Bhavesh Shrimali) with the delicious lunch his mother (Richa Meena) packs for him. It’s hardly likely that a poor family can afford such a feast but food and films seal the bond of friendship between the two.

A scene in the film talks about modernisation reaching the village, which means not just the celluloid projector being replaced by a digital system but broad gauge tracks being laid, so that trains will no longer stop at the station and the tea stall will have to shut down.

The film is set around 2008 because Jodha Akbar is playing in the theatre, so it is strange that television, computers and mobiles haven’t reached this pocket of Gujarat. But one has to accept Nalin’s version of how it was because he can tell his story any way he wants to.

Swapnil Sonawane’s camera captures the last of the age of innocence, when joy could be snatched from little things, and childhood was relatively carefree and full of adventure.

Just as much as the magic of cinema, it is about the imagination of a child and the typical Indian jugaad. Not only is Samay able to make up stories from match box pictures, he and his buddies rig a projector from junk and make up their own films from bits of stolen reels, providing the sound effects on the spot.

There is some cuteness overload, and the kids posing in picture perfect frames, but for the diminishing community of true movie buffs, there is much to admire in the fable-like, bitter-sweet tang of the film.

The most heart-breaking scene comes towards the end, when audiences can see where the old film cans and reels end up.

Till then, Samay enjoys his furtive visits to the cinema and develops a fascination for light, holding up his hand to the beam falling from the projector, and taking very seriously Fazal’s words: ‘From light comes stories, and from stories come movies.’

He also says, ‘People are watching darkness for an hour — it’s all lies,’ but it is the light Samay seeks as he says, ‘I want to become movies.’

If Cinema Paradiso made the little boy’s dream come true, Samay has to be content with the start of a journey which may lead anywhere.

In its own way, the film also pays tribute to the tribe that cannot imagine cinema being anything but a large screen experience in a dark hall. And no rewind or fast forward button.

- MOVIE REVIEWS

Source: Read Full Article