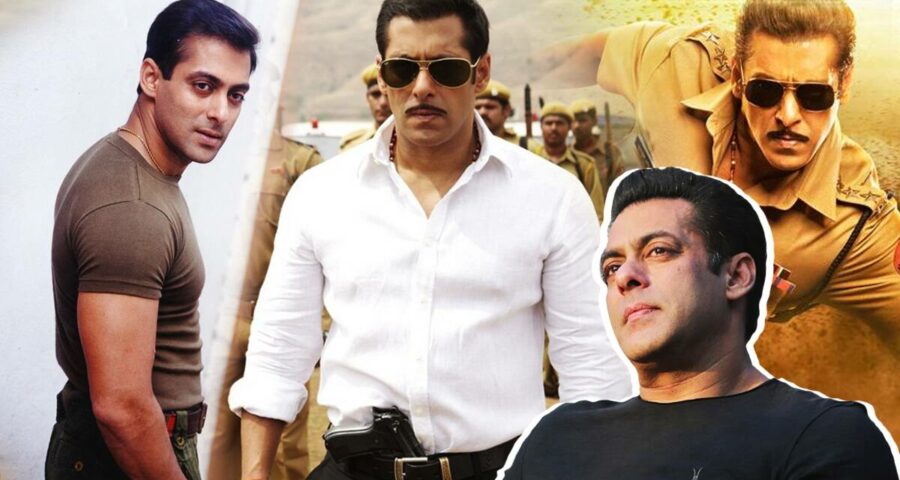

The mounting court cases, string of flops, the ultimate bad boy image — despite the many downs, Salman Khan has rolled on over the decades. If the Salman Khan of early years was a shy charmer, today he's a box-office juggernaut and a demigod of Hindi movie masses. Here's decoding the 'Bhai' myth.

Salman Khan is ‘Eid ka chand,’ at least on screen. Refreshingly secular at a time when India is plagued by growing bigotry and divisive politics, the Khan family (headed by his father Salim Khan) claims to celebrate all festivals, Christmas, Diwali, Ganesh Chaturthi and Holi but Salman Khan releases his much-awaited films — no matter how atrocious in content, they always have huge commercial blockbuster potential — on Eid. As far as Sallu fans are concerned, the festival marks the end of Ramzan and the beginning of Bhaidom. For more than a decade, perhaps since Wanted (2009), the Bigg Boss host has cornered the lucrative Eid market. The Bollywood calendar works slightly differently. Aamir Khan has Christmas, Akshay Kumar has Independence Day, Shah Rukh Khan has Diwali and so goes the pecking order of Bollywood. Due to the unprecedented second wave of Covid-19, Salman’s latest Radhe will open on OTT platform ZEE5’s pay per view service ZEEPlex besides theatres. A real-life philanthropist, the 55-year-old star has already pledged the proceeds of the film’s profits towards Covid-19 relief.

And profits there will be plenty. Because when Salman flexes his bulky muscles all kinds of logic are thrown out of the window, like his heroically combative, scene-setting Dabangg entry with opponents flying all over the place after each well-timed thwack. Salman Khan is all swag and millions of viewers seem to just love it. Mass appeal is his USP and he makes the most of it. The action-studded spectacles, audience-friendly wisecracks (though the Diya-Nadiya line from Radhe is a new low even by his own standard), dancey tracks, puerile humour, slick camerawork and above all, a superhero-style fireworks have come to be associated with the Sallu formula. Much of it typically refashioned from the masala entertainers of the South (think a fusion of Rajinikanth, Chiranjeevi, Ravi Teja… suparrrr sir!) to suit the star’s extant “being human” image. But it wasn’t always so.

Desi Stallone

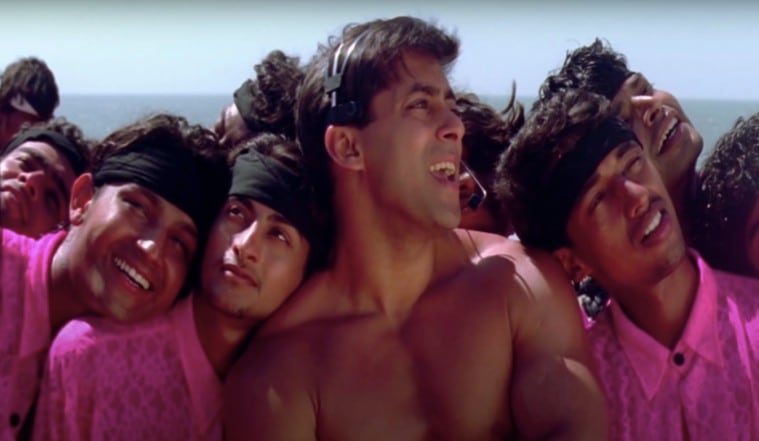

Salman is today a God-level action star but in the 1990s, this was very much an Akshay Kumar-Suniel Shetty-Ajay Devgn territory. In fact, all the Khans including Saif Ali Khan — who has enjoyed a career renaissance of late — started out as loverboys, endearing themselves to the ’90s audiences with their breezy earnestness. The melodiousness of their music can still be heard on late night radio playlists, a throwback to the time when the fresh-faced Salman strummed guitar on the dreamy ‘Saathiya yeh tune kya kiya’ with Revathy or the Raj Kapoor-inspired ‘Kabhi tu chhalia lagta hai’ with Raveena Tandon (god bless SP Balasubrahmanyam). Cut to: ‘Oh oh jaane jaana’ (from Pyaar Kiya Toh Darna Kya). Once again, Salman at his musical best, though this time he goes shirtless to show off a chiselled physique-in-the-making. In the coming years, the bare body reveal would become another of Salman’s draws, a sort of desi Arnold-Stallone. Between Maine Pyar Kiya, Love (a film most remembered today for the chartbuster ‘Saathiya yeh tune kya kiya’) and Patthar Ke Phool (‘Kabhi tu chhalia lagta hai’ is from this Salim Khan-penned movie) to the late-90s hits like Judwa (two Salmans for the price of one) and Pyaar Kiya Toh Darna Kya much had changed. In between, he gave one of the biggest Hindi hits, the record-breaking Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! and one of the most definitive comedies of its decade in Andaz Apna Apna. In both, he played Prem. The screen name became synonymous with his inimitable reticence, a product of the virtuous Barjatya school.

The Salman Khan of these early films had a shy charm about him and he maintained that note of innocence well through the ’90s. Before he assumed the mantle of ‘Bollywood’s bad boy,’ he had the opposite image even though his fans tended to forgive his many misadventures and misogyny. Back then, he wasn’t known as a brattish man-child but rather, as famously easygoing and friend’s friend, sincerely unmindful of his own huge star wattage. Things in Hindi cinema reshuffled after the ’90s ended. In hindsight, it was a tectonic shift. A moment of reckoning. Salman took a long time to fit into the new place that was Bollywood now. While Aamir and Shah Rukh Khan were sharp enough to cash in on their market value during the rise of the multiplex era circa-2000, Salman Khan seemed to have missed the spirit. With him, the conventional wisdom went that he wasn’t a pro at career management, unlike other Khans. Does anyone remember Tumko Na Bhool Paayenge, Yeh Hai Jalwa, Kyon Ki…, Lucky: No Time for Love and Marigold? Bet even Salman doesn’t remember. But the string of flops didn’t slow him down. Looking back, one of Salman’s biggest game changers was Tere Naam, in 2003, in which he played a tortured lover. The tragic love story had another tragic angle — that hairstyle, which was either hideous or happening, depending on whom you ask. Okay, it WAS a disaster (only marginally tolerable than Suryavanshi, which isn’t saying much) but then why did it become such a craze? There’s no clear answer and it makes no sense to dig deeper, just as there’s no reason why his tacky towel dance became an insane hit.

In The Game

After Tere Naam, it was No Entry and Wanted that gave him the box-office bona fines. Though hugely popular, even during his worst phase when he was in and out of jail (the hit-and-run and blackbuck poaching case that were turned into a soap opera by the media) somehow his films never matched up to his off-screen legend. Even a superstar like Salman needs a hit to remain in the game. And along came Abhinav Kashyap’s Dabangg in 2010, a resounding success that reinvented Salman. Govinda, Suniel Shetty, Jackie Shroff, so many of ’90s leading men had been counted out in the New Bollywood. Salman, on the other hand, floated by on his critic-and-box-office-proof profile, but for how long? Every star appears jaded and complacent after thirty years on the floor, unless you are that mythical creature called Rajinikanth. Or you grow a beard and frogmarch over into the margadarshan mandal like Amitabh Bachchan, a comfortable place where no one can unseat you anymore.

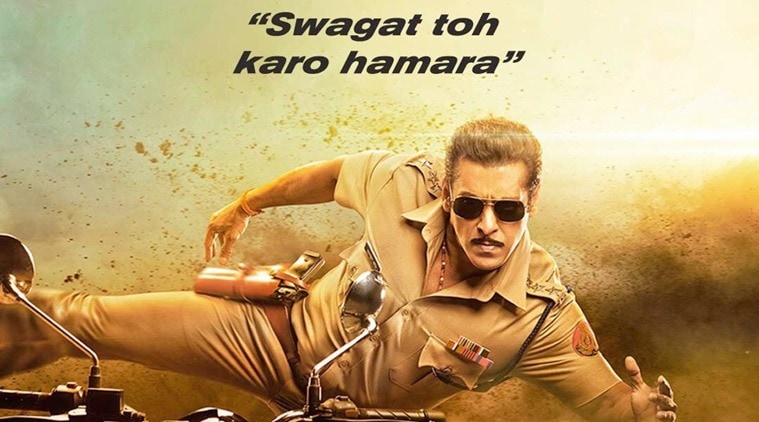

But Dabangg’s timing was perfect. A fun romp, it gave his fans something to throw coins at and just about enough to keep critics glued who, for the first time, felt Salman was on to something. Salman’s badass supercop Chulbul Pandey topped the charts and officially, his lucky surge began. Then and now. He soared on the big screen with the subsequent Dabangg franchise. Plus, Ek Tha Tiger, Sultan and Race 3. The Marlboro Lights-style machismo and celluloid heroism has worked for Salman and his mostly male mass audience base — it is strange to think of a time, some light years away, when women audiences loved their Prem. His films are now an ode to his own mythology.

The Kick (2014) credo ‘Dil mein aata hoon samajh mein nahin’ best epitomises the heart-to-heart connection and emotional impact he has on his legion of followers. And how apt that the son of one of Hindi cinema’s greatest screenwriters spits that phrase with a front-stall punch. ‘Ek baar jo maine commitment kar di, Character dheela hai, Jumme ki raat hai, Hum yahan ke Robin Hood hai, Mujh par ek ehsaan karna ki mujh par koi ehsaan na karna’ and now, the reference to his eligible bachelorhood and a life lived on his own terms in Radhe’s title track, Salman’s “being human” qualities are increasingly feeding into his cinematic myth. What is this myth? That everyone’s favourite Bajrangi Bhaijaan is a man with a heart of gold, a paragon of secularism (implicit in the Kabir Khan film’s title), a friend of the poor, a champion of charity, a larger-than-life personality who prefers living the life of a hermit and a misunderstood God’s child. “There’s this myth called Shah Rukh Khan and I am its employee,” so said the usually voluble Shah Rukh Khan once. Cocky or modest, you decide. In Salman’s case, he owns the myth. There’s no employee in sight. Only a sea of worshipful fans who think their beloved Bhai can do no wrong.

Source: Read Full Article