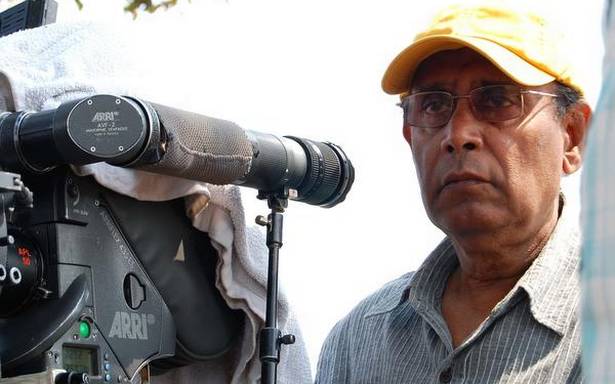

He was a poet whose cinema spoke the language of fantasy, song and fable even as it addressed sociopolitical concerns

With the departure of Buddhadeb Dasgupta, we have lost a great poet and auteur. He belonged to the generation of filmmakers who entered the scene after the first wave of pioneers in Indian art cinema like Ray, Ghatak and Sen. He also represents the post-Emergency era, whose social concerns, political vision, and aesthetic sensibilities were honed in the post-Nehruvian age of disillusionment with establishment of any kind — social, political, cultural and aesthetic. The promises of the nationalist project as well as the revolutionary dreams of the radical movements — both were on the wane, leaving a huge vacuum within the larger political imagination.

Also Read | Get ‘First Day First Show’, our weekly newsletter from the world of cinema, in your inbox. You can subscribe for free here

From his first films — Dooratwa (Distance, 1978), Neem Annapurna (Bitter Morsel, 1979), Grihajuddha (The Civil War, 1982), and Andhi Gali (Blind Alley, Hindi, 1984) — one sees an auteur-in-the-making, with a distinct aesthetic vision and narrative style. Also evident are his primary sociopolitical concerns and thematic trajectories, and the larger political anxieties and uncertainties that loomed large over these narratives about individuals, their struggle for survival, personal ambitions, love affairs and marital conflicts. In the later decades, his works became more complex and nuanced, more intensely poetic and melancholic. And in a filmmaking career that spanned four decades, he made some of the most memorable works of film art, leaving behind an enchanting trail of dreams, fantastic but also nightmarish.

Poetic vision

In terms of form, he strode a path of his own. A promising and well-known poet before he ventured into cinema, he brought a certain kind of poetic vision, and also form, to his filmmaking style through his lyrically intense and metaphorically charged imageries. He was never a prisoner to the prose of ‘realist-naturalist’ modes that ruled the ‘art cinema’ narratives of his times. Instead, he drew his creative energies from poetry, as is evident in the visual fluidity and oneiric imageries in his films. Breaking away from linear storytelling and inane symbolism, he explored new modes of narration, blending the inner lives and destinies of characters with several other strands of fantasy and dreams, songs and fables.

In his world, we come across minstrels, magicians, wrestlers, nomadic singers, and performers who wander in and across his narratives, along with motifs like birds and animals caged and flying free, aeroplanes — a constantly recurring image — and old, dilapidated mansions, the ruins of the past that house memories, dreams and ghosts. Sudden snatches of songs, flights of poetry, colourful processions and drunken reveries, epiphanies, monologues, and apparitions populate this world.

Still from ‘Charachar’.

Leaving behind the linear logic of prose and its claustrophobic rigidities, Dasgupta’s imagination was more at home in the exteriors; in every film, one can see more exteriors than interiors. In true poetic mode, it was such concrete and visceral exteriors that he used to express and reveal the mysterious and dark interiors. Through them, viewers are transported to a magical realm of vast and desolate landscapes, undulating terrains, enigmatic skylines and hillsides, silent and verdant stretches of thick vegetation. (For instance, the poetic opening and ending shots of Uttara (2000), where the camera lingers in a dense grove of trees, where everything stands still but for the falling leaves.)

Shifting time

Singing and dancing minstrels and their processions — both in the rural expanses and the cityscapes — are another recurrent motif punctuating his narratives; they seem to function like the chorus in Greek drama, suddenly shifting time, space and context into another realm of experience and understanding. In his later films, the narratives became even more magical and mystical, where the past and present blend, the living, dead and undead converse with each other, and apparitions take corporeal form to make amends or repent for unlived lives.

A strong and persistent undercurrent of politics runs through all his films; if it is the radical extremist politics of the late 60s and early 70s that haunt his characters in the early films (Dooratwa, Andhi Gali, Grihajuddha), it is the spectre of communalism, state violence and religious intolerance in later films — Uttara, Swapner Din (2004), Anwar ka Ajab Kissa (2013), Urojahaj (2018). References to historical events abound: the Sepoy Rebellion, the freedom struggle, Partition, the China war — Tahader Katha (1992), Bagh Bahadur (1989) — as well as recent instances of communal violence in Gujarat and state repression. These references connect and place the personal tragedies and dilemmas of the characters within their larger sociopolitical realities, often turning personal narratives into national allegories of sorts.

Still from ‘Uttara’.

Lost ideals

Deep anxiety and anger about the erosion of values and loss of dreams surface in many narratives: Shibnath, the protagonist of Tahader Katha, who has returned after 11 years in prison fighting for the country’s freedom, finds himself adrift and insane in the new India and repeatedly asks his former colleague-turned-approver and upcoming politician: ‘What happened to our dreams?’ In Grihajuddha, the heroine whose brother has become a martyr, reminds his friend and her lover, who is ready to make compromises for middle-class comforts, ‘You had strange dreams then’. In Andhi Gali, the hero Hemant, who has run away from Kolkata to pursue his middle-class dreams in Mumbai, turns violent when reminded about his radical past and its betrayal. Such early resonances of idealism about political and class struggle seem to wane in the later films, where we only encounter random acts of violence, as in the opening sequence of Swapner Din (2004).

For a filmmaker who pursued and created film-dreams all along, his last film Urojahaj (The Flight) can, in retrospect, be considered his swan song. It is a lyrical film where time and space, past and present, dream and reality, dead and living, mix and mingle. It is a tale about a small-town motor mechanic whose dream of flying is brutally crushed by the System. It is indeed a gut-wrenching reminder of how dreams are becoming impossible and are even considered seditious in our times.

Adieu, Buddhadeb Dasgupta, the filmmaker who created a world of dreams for us to seek solace in and find ourselves.

The writer is a Kerala-based, award-winning critic, curator, director and translator.

Source: Read Full Article