‘The idea of this movie is to trace these journeys and not to blame.’

‘We could have talked what happened in 1948. This is what the Israelis did. This is what the Palestinians and Arabs did.’

‘We didn’t want to go there.’

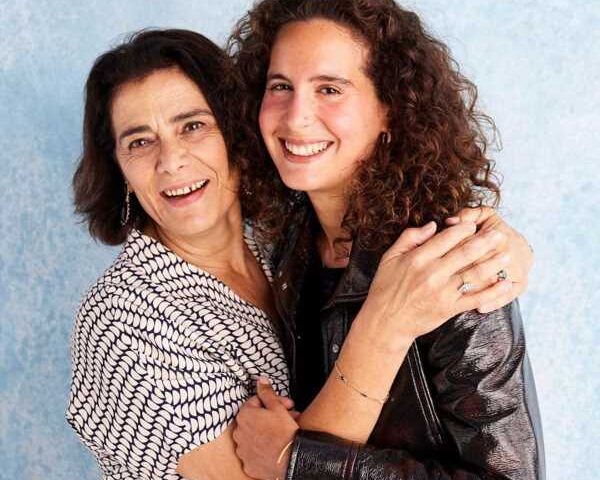

In the autobiographical documentary Bye Bye Tiberias, French-Palestinian-Israeli actress Hiam Abbass (Succession, Ramy, Miral, Munich), working with her film-maker daughter Lina Soualem, tracks the lives of four generations of Palestinian women: Her grandmother Um Ali, her mother, herself and Soualem.

In 1948, as the Jewish State of Israel was established, Palestinians were forced to abandon their homes.

That was also the case of Um Ali and her husband Hosni Tabari (Abbass’ grandfather).

They had to leave their home, located close to Lake Tiberias, also known as Sea of Galilee, a freshwater lake in Israel, north of the Palestinian administered territory of the West Bank and bordering on the right with Syria. Jesus is said to have walked on the water of Sea of Galilee.

The film follows the hardships Abbass’ grandparents faced as they became refugees in their homeland, Palestinian Arabs living in camps, inside the newly created Jewish State.

Abbass grew up in this atmosphere with her parents and siblings until the age of 23 when she left her family’s home in the village Deir Hanna, located in Israel, for Europe to pursue her acting career.

Bye Bye Tiberias also focuses on the separations between Abbass, her mother and grandmother. That separation was out of choice from Abbass’ point of view, but an aunt of hers accidentally landed in Syria during the upheavals in the region and was never able to return back to Israel to be with her family. In the film, Abbass, now a French citizen, makes a surprise visit to meet her aunt in Syria.

Soualem was born in Paris, to French Algerian actor Zinedine Soualem and Abbass. Throughout her childhood, Soualem traveled to Israel to spend time with her great grandmother and grandmother until the idea of the film emerged.

Bye Bye Tiberias premiered in September at the Toronto International Film Festival. It is Palestine’s official entry for the Oscars, and will play at the Jio MAMI: Mumbai Film festival.

Aseem Chhabra spoke to Abbass and Soualem in Toronto, a few weeks before the war between Israel and Hamas began.

This is such a beautiful film. How did the process start? Because Hiam, you say at the beginning of the film, that you were reluctant to talk about why you left your home. Lina, did you have to convince your mother to make this film?

Lina: At first, she was willing to be a part of the film, but then she realised what it would mean and it seemed harder.

It took long discussions to put her at ease, trying to film her, without digging too much into intimate things.

Hiam, you have been an actress for a long time. How did you agree for this when you realised that you will not be acting but narrating your own story?

Hiam: Yes, it’s true. The focus on my grandmother and mother almost brought me back to who I am, in a way, because these women really influenced my life in a big way.

My mother in direct education, and my grandmother with the way she was a part of the history and whatever she communicated to me about survival.

When the idea of this movie was born, Lina felt my resistance.

At one stage, I even say in the movie ‘Stop digging.’

But you willingly flew to back to Israel to make the film.

Hiam: But she’s my daughter. She’s not a stranger.

We talked enough and she prepped enough.

Anytime you let anybody go into your personal life, you are hesitant. You are right that it’s easier for me to put on costume and makeup, and the body of someone else.

Lina had previously made a documentary about the Algerian immigration in France (Their Algeria), and she had the experience of working with the personal to the collective memory of a group of people.

She was always trying to bring the process to be natural and easy.

I trusted her brain and her creativity.

The film was being made a long time ago. Hiam, you had started to make videos of your daughter with your mother.

Hiam: That was her dad (Abbass’ ex-husband Zinedine Soualem). He was very keen on filming everything.

He’s French from an Algerian background and would be really fascinated when he would visit Palestine with me and Lina, when she was young.

It was very important for me to pass on the family connection to Lina — the traditions, the food, the life, the village, the garden and the house — everything that you see in the movie.

Lena was lucky that those visits were well documented.

What about the archival footage of Palestinians leaving their home as refugees? Was that easily available?

Lina: There are two types of archives.

There’s the personal archive and then the historical archives, which I looked for many years.

Those are dispersed in many different places because as there are no national Palestinian archives.

I found footage in Britain and through UNESCO.

I had to look for images everywhere because it was important for me to put other faces also on the story, not only the ones of my family.

One of the things that is hardly talked about in the film is Hiam’s life as an actress and when she left Palestine.

Lina: Something that was very clear from the beginning. It’s not a film about my mother, her career and achievement as an actress.

It’s a film about four generations of Palestinian women, and the transmission between generations.

My mother is one of these women. Of course, I have to go through her to get to the other women. She is the guide in the film.

Hiam, did you move to France from Palestine?

Hiaml I first moved to England and then to France.

I understand this is not the subject of the film but as an Arab actress, you still have your beautiful accent. Was it a struggle to establish yourself? You went to France as an immigrant.

Hiam: To be honest with you, I never had a dream to become something different than who I am.

Somehow my work imposed itself in that way, in my path.

Whatever accent I have, it was used for the characters that I played.

I never felt like I had to change myself or my accent for any reason.

I am lucky to have worked with people who took me for what characteristics I have to serve the character.

My career in English language films comes with who I am and what I can do. I never played a purely American or British character.

Many of your films were set in Palestine or some other Arab country.

Lina, what did you learn while making the film?

Lina: As a daughter, you only know your mother as a mother.

So for me, it was fascinating to be able to grasp what my mother was like as a young woman, a teenager, a child.

Hiam, what did you learn during the making of the film? You had to think about yourself, your life, what could be in the film.

Hiam: Honestly, I don’t know. It’s a very tough question. But thank you for asking.

I just don’t know what the answer to that is really. Maybe I am still in the process of putting a distance between me and the movie.

Did you understand your mother or grandmother better while talking about them?

Hiam: Really, they are part of my memory.

It’s not like something that I suddenly discovered.

What was interesting was how Lina put the pieces together. I feel like one of the pieces.

Whoever I am, whatever I am, I am a piece of a whole chain of generations that had been transmitting to one another, the strength of survival, the strength of how a woman should achieve her life as a woman, despite the traditions, the social and political context.

I appreciate who my grandma, my mother and my aunt from Syria were.

Also my fears and struggle, while making the movie were so small compared to the struggles of the women that I am talking about, and what they had to go through in their lives.

That group of women and men at the end of the films lining up for a photograph, are they all your siblings?

Hiam: Yes.

I counted 10 of them.

Hiam: Yes. They all came for this one gathering, three of them from abroad. These gatherings are essential and we try to keep up with that for the memory of my parents.

There is politics in the film from the beginning. It’s what happened when Israel was created. There’s one point when you point to Lina and say, Syria is this side and there is Jordan, and Lebanon on the other side. While Palestine is in the middle, mostly merged with Israel. I don’t hear any bitterness or anger in your voice.

Hiam: I don’t have that. The idea of this movie is to trace these journeys and not to blame.

It is a situation, a history, it’s the truthful story.

This is my story.

I am not trying to prove anything and I am not bitter.

We could have talked what happened in 1948. This is what the Israelis did. This is what the Palestinians and Arabs did.

We didn’t want to go there.

It is the story and the journey of these four generations of women with the political context of the real history.

This is their life, although it cannot be thought of without talking about the politics which directly affected their most intimate choices.

It is a collective story, like when families are scattered, separated, because of the frontiers of the borders and the wars, you cannot escape.

Source: Read Full Article