The premier South American rivalry may not be so violent today, but Copa final provides enough plotlines and narratives

After seeing off Peru in the semifinals, Neymar was asked which team he wished to face in the title decider. “I want Argentina,” he said spontaneously. Realising the faux pas, he paused and tried to make amends. “I have friends in the team, like Angel (di Maria) and (Leandro) Parades. In the final, Brazil will win.” He carefully evaded naming his closest Argentine friend, Lionel Messi, for he knew that his answer could easily be misinterpreted.

But Neymar’s statement inevitably provoked the rage of Brazil’s football clan. Bonhomie between footballing rivals isn’t appreciated at Copa America. So before Sunday morning’s final (India time) against Argentina, Neymar posted another statement on Instagram: “I’m Brazilian with a lot of pride, with a lot of love. My dream was always to be in the Brazilian national team and hear the fans singing. I’ve never supported or will support against anything Brazil is competing for, whatever the sport or modelling contest.”

This time, he did drop Messi’s name: “He is my closest friend, but I will put my friendship on the line.”

With this war-cry, a slow-burning tournament, played out in hollow stadiums, with a cumbersome format, at unworldly hours across Europe and Asia, suddenly flickered into life. For a few hours, the eyes and ears of the footballing world would wander from Wembley to the Maracana, two historic stadiums that stand as symbols of distinct footballing cultures.

Rivalry over the decades

The multi-hued narrative arcs of the final are irresistible, something the Euros can neither replicate nor imagine. Argentina and Brazil are football’s fiercest rivals and the antagonism between the two nations has often spilled onto the ground.

The first two of their finals in the then South American championship, in 1937 and 1939, did not last the full course due to pitch invasions. In 1937, when Argentina won, Brazil’s fans alleged their players were racially abused and stormed onto the ground. Two years later, Argentina’s supporters stopped the match after a contentious refereeing decision resulted in Brazil’s winning goal.

Post-war, players ending up with fractured legs and disarranged facial features was routine. Sometimes the crowd was so hostile that the teams had to lock themselves in the dressing rooms. There was an instance in 1946, when a Uruguay-born Brazilian player, Francisco Aramburu, had to flee at the end of the tournament because he was alleged to be a spy and the Argentinian secret service was tracking him.

But once Brazil started winning World Cups, they stopped caring for the Copa, and their rivalry in the continental championship was diluted. But repeated World Cup setbacks made Copa prestigious again for Brazil.

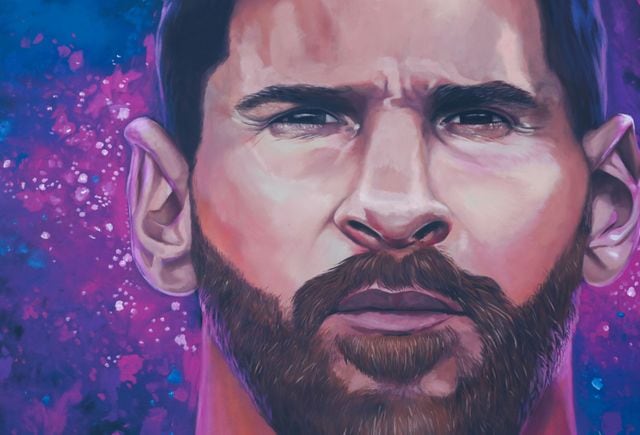

From the emergence of Diego Maradona began the bout of idols. Though the peak years of Maradona and Pele never collided, they were always at opposing ends of all GOAT discussions. The tradition rolled on, in fits and bouts, before acquiring epic levels with Neymar and Messi, two close friends, once teammates and neighbours, now in each other’s way in pursuit of glory with the national team. This is also an opportunity for the Big Two to wipe off the accusation that they are club metronomes detached from the cause of their nations. It is also a chance to move out of the towering shadows of Maradona and Pele and to stand as champions in their own right.

Time running out

Copa glory has evaded Messi narrowly — first in 2007 (against Brazil), and then in 2015 and 2016 (against Chile in tiebreakers). Messi would remember the second of the shootouts vividly, when he kicked the ball over the crossbar. So gutted was he that he deliberated on retiring from international football before being talked out of the hasty decision.

There is also a feeling that the glory may elude him forever. If not now, Messi shall be forever considered inferior to Maradona in his ability to win tournaments. Moreover, there is a sense of desperation, as Argentina have not claimed any significant title since the Copa triumph in 1993. A 28-year-old period of hurt wherein several golden generations departed with unrealised dreams. And the brightest of their talents is at the risk of retiring without a single major trophy draped in an Argentina flag. There’s of course the World Cup next year but the clock is ticking furiously on Messi’s career.

Unlike Messi and Argentina, Neymar and Brazil aren’t running out of time. Neymar is just 29 and Brazil have won the championship as recently as 2019. However, there’s growing frustration that Neymar is not winning enough trophies commensurate with his potential. He is just five goals behind Ronaldo in the list of Brazil’s all-time goal-scorers and has raced ahead of legends like Romario, Zico and Bebeto, but has not yet been accorded the status of a legend himself. His tantrums and theatrics have not gone down well with sections of Brazil’s feverish fan-base. A World Cup would be, no doubt, the Holy Grail but a Copa would be a good start. Any trophy would be better than no trophy.

More than the trophy, they would not stand losing to Argentina – of all teams – at their stomping ground, where they have not lost since 1950, winning 22 and drawing six matches at the Maracana. Both teams come in terrific form too. Argentina are undefeated in 19 competitive games; Brazil in 18. Even without the shades of history, a high-class contest awaits. A contest wherein, they would keep friendships aside and put their body and soul on the line.

The Argentina-Brazil rivalry might be less violent these days, but it remains undiluted in its ability to stop the world, be a spectacle and weave multi-coloured narratives.

Tale of two stars

Messi & Neymar need to own the big night

Messi, missing when it matters

The last time Argentina and Brazil met, in a friendly in Saudi Arabia, Lionel Messi’s goal turned out to be the difference. In 10 games, he has netted five goals against the Selecao, but none of them has arrived in a competitive game, including high-profile ones as the Copa America final in 2007 and World Cup qualifiers in 2018. In both instances, Messi was a largely peripheral figure, subdued by tight marking. That he has not scored in any of the four significant finals he has played is a common grouse too.

Messi in fine form

He has been at his influential best, scoring goals, helping with goals and bossing opponents. He leads both the scoring (five goals) and assists (four) charts, besides leading his team with an iron will to succeed. As often is the case, each time Argentina have looked stuck, Messi has provided the spark. He has relished in the free-roaming role, unburdened of formation-specific roles. His drive to win an international title has seldom looked so perceptible.

Argentina, defence first

Bursts of Messi’s brilliance apart, they have been more or less flat in the final third. A starting eleven that mostly comprises fresh faces, with veterans Sergio Aguero and Angel di Maria consigned to the bench, they have struggled to produce the enterprising brand of football their fans demand. They are prone to vertical passing and losing shape. Though the defence has held on resolutely, conceding just three goals in six games, they are still vulnerable to pace and pressing.

*******

Average against Argentina

In 10 games against Argentina, Neymar has found the back of the net just three times and assisted in four goals. However, in his last two games against them, he was adjudged player of the match. In his last competitive game against them, in a World Cup qualifier in 2016, Neymar was terrific, scoring a spectacular goal and assisting another, a performance he counts among the best.

More playmaker than goal-scorer

No one calls Neymar selfish these days, not in this tournament at least. He has been busy helping his teammates than swelling his own goal tally. He has scored just one goal, but masterminded three, including the one against Peru in the semifinal, and had pre-assists in two more games. Like with PSG, Neymar starts on the left side of the field, but has repeatedly occupied the space behind the centre-forward, where his play-making skills have come to the fore.

Brazil, flexible to core

Brazil have alternated between free-flowing and rigid styles of football, without exceeding the limits on either. They could embrace a full-throttle attack, they have players for that, but their backline is one of their best in recent times (they have conceded just four goals in 12 games). Some of the romantics have criticised Tite’s uncharacteristic caution, especially playing with two defensive midfielders, but defeat at the hands of Belgium in the 2018 World Cup quarterfinal has shaken the romantic in the Brazilian manager. Nonetheless, when the mood seizes them, this Brazilian side is capable of producing throwback magical moments.

Source: Read Full Article