While following the Kalakshetra style, the three dancers rose to new challenges at the Yuva Nritya Utsav

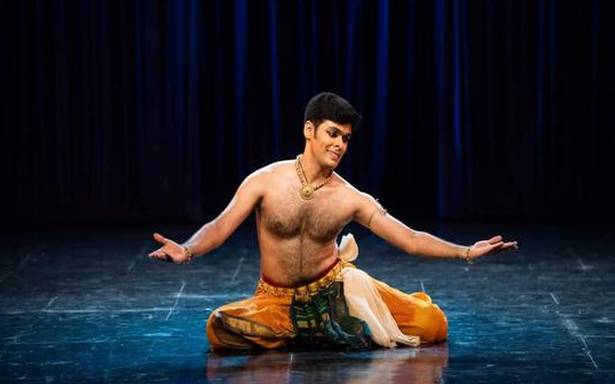

Kalakshetra’s ‘Yuva Nritya Utsav’ featured several Indian classical dance styles. Three artistes, Girish Madhu, Sreedevi Jayakrishnan and Janet James, who presented Bharatanatyam, were all alumni of Kalakshetra, whom we have earlier seen playing major roles in their alma mater’s dance productions. So it was rather difficult to view them as soloists.

The lanky Girish Madhu has a serene stage presence, which is why he plays Rama. He is also part of Kalakshetra’s faculty, and has been working with dancer-choreographer Sheejith Krishna, a former faculty and alumnus. Although Sheejith’s style remains the same, adapting to his unique choreographic interpretations was a challenge for Girish, but he rose to the occasion with a flawless performance. A little more energy would have made his portrayal more convincing.

New ideas

Girish presented Adi Sankara’s Shiva Panchakshara Stuthi in ragamalika, (music composition Kodayanallur Venkataraman) with imagery based on the concept of the Pancha Kritya (five functions of Nataraja’s dancing posture) from Thirumandiram. The piece went beyond a literal translation of the descriptive sloka, to show the uncoiling of the energy pathway through the chakras to the top of the head, to realisation. The phalasruti regarding attainment of Shivaloka was taken as an illusion, and just as a curtain hides the deity, the hands in pataka hasta moved in front of the face.

This is how Sheejith expresses himself, through traditional language but through unconventional ideas. The ideas can actually take attention away from the dancer, and hence requires a strong performance to prevent this.

Next was a keerthana on Yati, a concept in tala, where rhythmic syllables are organised in a geometric pattern that create shapes when written. An example is the Mridanga Yati that looks like a mridanga drum. It begins with a few syllables, builds up, then returns to the original number. The Yatis were presented through Shiva Ananda Tandavam in ‘Ananda koothadum pada malar kanden’ (lyrics by Nirmala Nagarajan, music composition by S. Rajaram in ragamalika, talamalika). It was an exciting choreography by Sheejith as the complex rhythm unfolded with each theermanam, with sollus matching the drums.

Sheejith was on nattuvangam, K.P. Ramesh Babu on mridangam, Jyothismathi Sheejith on vocal, and Easwar Ramakrishnan on the violin.

The abhinaya was also novel. A Surdas poem ‘Vrikshana se mati le’ (Madhuvanti) spoke about the selfless tree that continues to give shade, flowers, fruits despite being ill-treated. The philosophical message was conveyed through angika abhinaya — the graphic use of limbs, not the traditional gestural language of Bharatanatyam. With minimal movement and set in an unhurried pace, the music and the mood was allowed to wash over you. Jyothismathi’s melodious voice was poignant. The silence contrasted well with the subsequent vibrant Desh thillana (Adi, Lalgudi Jayaraman) with unorthodox steps, including repeated theermana adavus and alarippu adavus. The performance ended with ‘Vande Mataram’.

Fine footwork

Sreedevi Jayakrishnan

Sreedevi Jayakrishnan is also a Kalakshetra alumnus, who is now on the faculty and in the repertory. She is a versatile and bright dancer, whose timing, nritta finish and expressions are impressive. Over time and with mentoring by senior dancers, she could improve greatly.

Her repertoire was a mixture of choreographies by different artistes — some effective, some uneven. To illustrate, the opening ‘Krishna Karnamrutham’ slokas written by Bilvamangala Acharya and tuned in ragamalika, talamalika by Kottayam Geminish, were visualised by Jayakrishnan. The music was enchanting and some scenes such as those on the banks of the Yamuna were well portrayed, but there was no continuity in the narrative.

It was the same with the Nattakuranji padavarnam, ‘Ma moham tane’ (Rupakam, K.N. Dhandayuthapani Pillai), visualised by K.P. Rakesh. The nritta aspect was exciting — great theermanams guided by Rakesh (nattuvangam) and R. Karthikeyan (mridangam), and excellent execution by the dancer. The ‘kais’ left much to be desired though. The first half was dull, the singing and the many repetitions, especially in the anupallavi line, ‘Emaattram sheida kallvan’, had little to say. The second half picked up speed as Sreedevi added energy to her steps.

Again, the piece on Jhansi Rani (ragamalika, Adi, composed by K.P. Nandini and Binu) visualised by Jayakrishnan had clarity but the treatment lacked depth. The thillana (Sindhubhairavi, Adi, Lalgudi Jayaraman) was the crowning glory of the recital.

The clever mix of rhythm with melody by the composer was handled with professional ease by Binu Venugopal (vocal), K.P. Nandini (violin) and J.B. Sruti Sagar (flute). The dance composer, Hari Padman, used variations in speed and matched steps to the rhythm of the music, but took care not to get lost in speed. Sreedevi proved that she is a well-rounded product of Kalakshetra.

Clear and concise

Janet James.

Janet James, apart from being an alumnus of Kalakshetra, is a student of Shantha and V.P. Dhananjayan. Guru Shantha on nattuvangam was at the helm along with K.P. Anilkumar on mridangam.

All choreographies were well polished by the senior artistes, and this helped Janet showcase her flexibility, rhythmic sense, and expressiveness. The entry in the opening Bhoomanjali (Shudda Saveri, misra chapu and Adi) composed by J. Suryanarayanamoorthy, in Anjali hasta, a graceful torso deflection, and the Alidam mandala bheda, hardly seen nowadays, was poetic.

The virahotkhandita nayika in ‘Sakhiye inda velaiyil’, Anandabhairavi, Adi swarajathi (Thanjavur Quartet), requests her friend to take a message of love to Rajagopala and bring him to her. There weren’t too many repetitions or gestures to confuse the audience, nor was there any melodrama or coquetry. The portrayal was clear and concise.

So too with the nritta. Though the theermanams were Kalakshetra’s original catchy rhythmic sequences, Shantha changed the ‘eduppu’ to samam filling gaps with karvais. This requires some effort as the song itself has a delayed start, but it worked well. Janet proved up to it as well.

While it’s not recommended, Janet repeated the bereft nayika in the subsequent piece as well, the Jayadeva Ashtapadi, ‘Nindathi chandana’. The only difference being that here it is the sakhi who is describing Radha’s state to Krishna.

Janet has to traverse some distance before tackling such deep emotions, but Radha’s agony was clear, especially when she tried to escape Kama. The soft melody was handled with delicacy by K. Hariprasad (vocal), T. Sashidhar (flute) and N. Ananthanarayanan (veena).

‘Sariga kongu,’ a short javali (Suruti, Adi, Ghanam Seenayya) visualised by Rukmini Devi, a Desh thillana (Adi, Ranganayaki Jayaraman), and the Subramania Bharati song ‘Bharata samudayam vazhgave’ (Behag) were the other pieces. The thillana contained some beautiful steps; the style seemed to celebrate the curves of Bharatanatyam, and this suited Janet well.

The Chennai-based author writes on classical dance.

Source: Read Full Article