Breakthrough launched the Ignore No More campaign in partnership with Uber India in March 2020 and concluded it in March 2021 with a comprehensive study on Bystander Behaviour.

Promoting positive bystander action to address violence against women has been a consistent focus area for Breakthrough. From the Bell Bajao campaign, which encouraged people to intervene in cases of domestic violence by taking simple actions like ringing the bell to its most recent Ignore No More and Dakhal Do campaigns, bystander action has been at the centre of their work.

Breakthrough realised that, for it to be able to achieve this goal, it is essential that they better understand the factors which motivate bystanders to intervene or prevents them from doing so, especially in the context of violence against women. The lack of existing literature on the issue, especially in the Indian context, further confirmed their rationale for undertaking the study.

Breakthrough launched the Ignore No More campaign in partnership with Uber India in March 2020 and concluded it in March 2021 with a comprehensive study on Bystander Behaviour.

What is bystander intervention?

Bystander intervention is a critical tool for preventing violence against women in public and private spaces. Bystander refers to individuals around a survivor when an act of violence against a woman is committed and has the potential or capability to act. Intervention represents any positive non-violent action (sans morally prescriptive codes) taken by a bystander to immediately stop an act of VAW.

Why do people intervene?

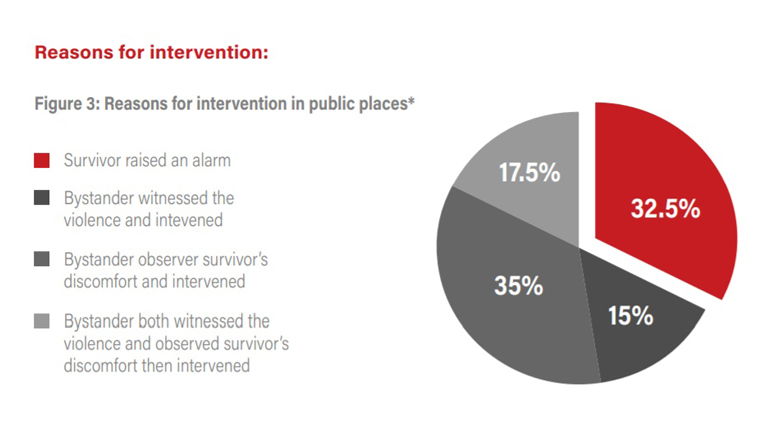

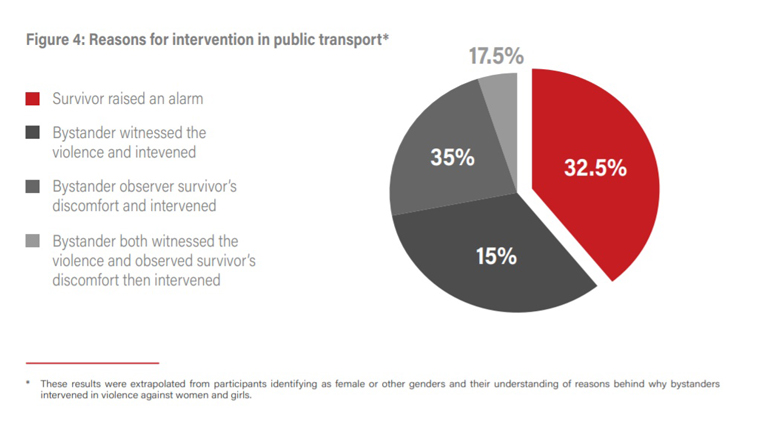

People who intervened provided a number of reasons for their actions:

- The urge to do the ‘right’ thing attesting to the presence of a strong moral component in speaking up.

- Some of the participants who were victims of child sexual abuse and domestic violence referred to unresolved rage at their own helplessness at the time of the incidents and how this pent up anger was triggered whenever they encountered abuse or sexual violence either themselves or witnessed others going through it.

- Some (both male and female) also talked about their own journey towards better gender sensitisation. Often it took them years to recognise certain kinds of violence and how it was symptomatic of skewed gender dynamics and patriarchal power.

- Some attributed it to their association with gender rights organisations either as volunteers, full time employees or general exposure to such spaces and issues.

Onil, a Mumbai-based participant and social worker spoke about how the processes towards setting up a sexual harassment cell in office and conversations with one of his female colleagues helped him first think about the notion of ‘consent’. This turned out to be instrumental as it propelled him to read extensively around the concept and how it was key to gender rights.

How have people intervened?

From an ‘active’ bystander perspective, intervention strategies and methods were influenced by multiple factors such as gender, age, socio-economic standing, gender rights awareness etc. Participants who had experience of intervention shared interesting methods of helping survivors. Often, speaking up and reprimanding the perpetrator had a huge impact in terms of stopping the incident. Other immediate kinds of intervention included:

A few of the participants were also drawn to some other methods adopted as redressal mechanisms for the long haul. A long-term intervention strategy shared by 30-year-old teacher Shakeel in Delhi involved community mobilisation. On being told by his female students about their difficulty of getting to school owing to eve-teasing on the streets around the institution, he and some of his colleagues came together to patrol the streets around peak hours. They also roped in the help of the cops and ensured regular patrolling. He says that it helped the girls get to school with a feeling of security.

The role of bystander action in enabling a survivor to speak up

- Social norms at play: Numerous participants who had experiences of intervention expressed their exasperation at the ‘silence’ of most victims of abuse and sexual violence. A few of the participants did acknowledge the critical role played by structural and social conditioning in influencing female behaviour and ‘choices’. Participants of the study pointed out how girls were taught from childhood to be submissive and not challenge their surroundings, at least not overtly. Yet it is important to unequivocally state here that though she is a product of larger processes she is not merely a hapless ‘victim’ but a complex being who negotiates these hurdles in multiple subtle and covert ways.

- Intersection of violence against women and violence against children: As stated above, some of the participants who were victims of child sexual abuse and domestic violence referred to unresolved rage at their own helplessness at the time of the incidents and how this rage got triggered and pushed them to intervene in cases of violence against women. However, some participants also expressed deep distress even now if and when they faced abusive situations. One of the participants, who is a survivor of child sexual abuse, painfully narrated how every time somebody tried to inappropriately touch her she ‘froze’ being unable to react in any manner.

Male and female bystanders: Is there a difference in approach?

There is also an interesting difference in the way men and women responded and intervened. Most men spoken to talked about the perils of being a ‘stranger’ while intervening for women unknown to them. Other passive bystanders questioned, often aggressively, the intervening man’s “right” to speak up for a girl who was clearly not related to him. Some men also discussed concerns over their safety as an important factor. This reality motivated some male bystanders to assume kinship or romantic relationships with the survivor to gain the ‘credibility’ to intervene.

Some men also talked about the difficulty of dealing with survivors who weren’t vocal about what was happening to them. A few highlighted how the situation turned messy when, despite their intervention, some women failed to acknowledge abuse had happened. A male bystander talked about how such an experience had prompted him to think of ways to quietly deal with a situation without bringing attention to a victim, hence the rationale for his strategy. This is in contrast with a similar scenario in which a female bystander intervened a lot more overtly. On witnessing a girl being harassed by her male co-passenger in a shared auto 22-year-old Aruna directly confronted the perpetrator.

In terms of women themselves dealing with sexual violence in public transportation they talked about using everyday objects such as safety pins as armour. Women travellers also demonstrated camaraderie with other fellow female co-passengers by strategically and quietly asking victims to move forward or aside without bringing attention to them. Avoiding potentially dangerous or violent situations is a common survival strategy employed by women while travelling.

A male bystander related how such an experience had prompted him to think of ways to quietly deal with a situation without bringing attention to a victim hence the rationale for his strategy. This is in contrast with a similar scenario in which a female bystander intervened a lot more overtly.

Survey results:

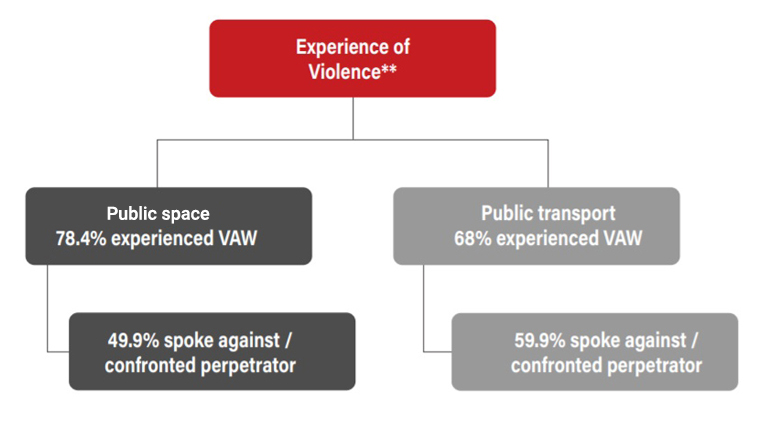

- 78.4% respondents who identified as female or other said that they have experienced violence in public spaces (does not include public transport).

- 68.0% respondents who identified as female or other said that they have experienced violence while taking public transport.

- 70.0% of respondents said that they would ideally like to help in scenarios of gender based violence by intervening/speaking out (individually or in a group).

- 54.6% of respondents said that they had intervened in an incident of violence against women in a public space.

- 5.3% respondents observed the discomfort of the woman/girl facing violence.

- 67.7% respondents said that their intervention resulted in the violence stopping.

- 45.4 % respondents said that they have not intervened in an incident of violence against women.

- 38.5% respondents said that they did not intervene because they did not know what to do.

- 31% of them said that they were worried about their own safety.

- 11.5% of them feel that they would be dragged into police/legal matters.

What can we do to promote bystander intervention?

- Shift from the protection approach to investing in agency of women and girls. Government should launch initiatives to promote individual action and behaviour against violence against women. e.g. Farishte Dilli Ke scheme

- Building accessible reporting systems, wide dissemination of reporting information, ensuring safety of the survivor and the bystander and setting up reporting tools in the transports, or other public spots. This will enable a conducive environment for preventing violence in public spaces.

- Gender Sensitisation for police personnel, citizen- police interfaces for better community action.

- Gender sensitive curriculums at the school level education system. Introducing gender equal practices among parents.

- Need to bring in systemic and policy level shifts for prevention of violence against women and girls.

- Shift from the protection approach to investing in agency of women and girls. Government should launch initiatives to promote individual action and behavior against violence against women. e.g. Farishte Delhi ke

The study was conducted with support from Uber India and IKEA Foundation.

Read the full report findings here: https://inbreakthrough.org/bystander-report/

Source: Read Full Article