The 18th century artist’s work was thought to be too sombre and not picturesque enough at the time

In the 18th century, Indian shores beckoned a number of European artists. Its exotic charm had cast a spell on many. William Hodges, Tilly Kettle, William and Thomas Daniell and others travelled to India either looking for patronage or to fulfill their commissioned assignments. A lesser known name among them was Baltazard Solvyns whose work didn’t get much attention at the time. While Hodges, Kettle and the Daniells painted the beautiful countryside and the rich and famous, Solvyns cast his gaze on the ordinary people of Bengal and created several extraordinary etchings.

Solvyns’s work is the focus of Delhi Art Gallery’s (DAG) ongoing exhibition at Bikaner House in New Delhi. The artist has been exhibited earlier and his books have been published but this is the first time that a complete series of 288 etchings from Les Hindoûs — published by the artist — will be on display.

A Belgian who practised marine arts in Antwerp, Solvyns arrived in Calcutta in 1791 and remained deeply involved with local culture, practices and customs over the next 12 years. It resulted in 288 colour etchings published in Paris as Les Hindous over four volumes between 1808 and 1812. DAG has put them together in one consolidated book called The Hindus: Baltazard Solvyns in Bengal.

Considered a seminal documentation today, Les Hindoûs failed to impress back then. Solvyns’s depictions of a solemn looking ‘Bannean’ (the Bania community of merchants or money lenders), a Brahmin standing by a river, a ‘Khitmetgar’ (Khidmatgars — manservants) standing behind his master’s chair, a Kayastha man working at his desk, a ceremonial procession, musical instruments, river transport on the Hooghly and even some quirky methods of smoking went unnoticed.

‘Cheroutery brahman’ [Srotriya brahmin] by Baltazard Solvyns. | Photo Credit: DAG

‘Kottery’ [Kshatriya] by Baltazard Solvyns. | Photo Credit: DAG

“Largely, I think it was a matter of aesthetics. Western audiences at the time thought that Solvyns’s work was too sombre, and not picturesque enough. His images have a gritty realism. That is not how Westerners wanted to engage with Indian people at that time. Appreciating the picturesque scenery portrayed by the Daniells was much easier,” says Giles Tilottson, curator of the show.

Tilottson, Senior Vice President, Exhibitions and Publications, DAG, in his essay in the book, reveals that Solvyns didn’t seek permission from the East India Company to live in Bengal which made him an unlicensed resident. “It limited the extent to which he was accepted into European society in the city. He was, for example, not invited to attend meetings of the Asiatic Society, which — given his curiosity about Indian civilisation — he would certainly have wished to do.”

In the city, he lived closer to the dwellings of locals which allowed him to observe them in detail.

Drawing parallels between Solvyns and other European artists of the time, Tilottson says, “Solvyns was not like any other European artists in India of his time. His contemporaries, like Hodges and the Daniells, were more interested in landscape, in topography, in the idea of India as a place with a splendid past. Solvyns engaged with present Indian society and its material culture, very closely. His images of musical instruments and transports are among the earliest visual documentation of them that we have.”

According to Tilottson, Solvyns employed a labour intensive method for the project and was far too ambitious in scale. After etching the image on to the metal plate, he applied colours using a cotton pad, so that he could print in several colours; and then finished each image by hand. “There are 288 prints: that is twice as many as the Daniells made in their series Oriental Scenery. I mean, who wanted 36 images of boats?”

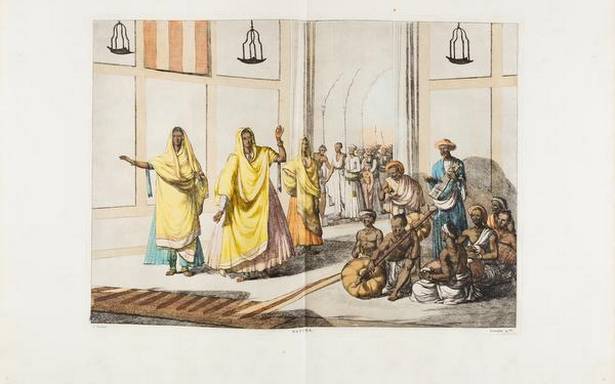

Barring a couple of etchings that showcase Europeans, Muslim couple and royals, the rest firmly focus on various aspects of the Hindu community in Bengal — castes and professions, festivals and ceremonies, costume and dress, renouncers, material culture, household servants and the natural world. They are realistic depictions of people and their daily lives. From a Mahabharat sabha to a rath yatra, a view of Kalighat temple, a khela dinghy — a pleasure boat used by Indians, musical instruments like jal tarang, Ramasinga (serpent horn), a bazaar scene, a sati procession, ascetics, nautch performance and representations of various castes and professions, there is so much to relish, understand and contemplate.

‘Ferry’ by Baltazard Solvyns. | Photo Credit: DAG

‘Long palanquin’ by Baltazard Solvyns. | Photo Credit: DAG

‘Ramayin Gayin’ [Ramayan gayan], 1808, by Baltazard Solvyns. | Photo Credit: DAG

Solvyns hasn’t depicted many women. Only a few etchings showcase a dai (wet nurse), a goalini (milkwoman), a woman from the lower orders, women during a nautch performance, and a well-adorned lady, amongst others. Solvyns claims that he has only made what he has seen and there were very few women he met on the streets.

As part of the section on renouncers, Solvyns shows a wide-eyed woman clad in white with her family beside, standing and staring in the forest even as food cooks in earthenware. In the accompanying caption, Solvyns says, “This name of Agooree is given by the Hindoos to those women who… prefer a life of exile and solitude in the woods and deserts.”

While Solvyns was earnest in his desire to showcase female members of the Tantric sect, he got it wrong in this picture. Tilottson writes in his essay: “He was perhaps a bit confused. He describes the aghori as a widow who has chosen ostracism rather than any of the options available to her.”

Solvyns’ diligent work isn’t devoid of other such instances of colour and misunderstanding. He met a few Sikhs in Calcutta and thought them to be a military tribe of Hindus. Solvyns believed that their founder Guru Nanak was a descendant of Timur who converted to Hinduism. The collection includes a plate depicting Sikhs.

Tilottson says: “His misunderstandings were inevitable, but you have to consider that his sources of information were the Indians he met. He didn’t make it all up. His perceptions mirror those of his informants.”

A portrait of a ‘bhishti’ or water carrier is described as Solvyns’s finest portrait by the curator. “The ‘bhishti’ is a powerful work because there is something very expressive about showing such a figure mostly from behind. It implies that this is not a person that anyone actually engages with: he just goes about his work silently. I think his most complex and successful compositions are the depictions of festivals in double-page prints in Volume 1. They are full of figures and rich in closely observed incidental detail.”

‘Behichty’ [bhisti], 1812, by Baltazard Solvyns. | Photo Credit: DAG

ON SHOW: The Hindus: Baltazard Solvyns in Bengal; Bikaner House, New Delhi; till August 20, 2021.

The writer is a journalist with interest in art and culture.

Source: Read Full Article