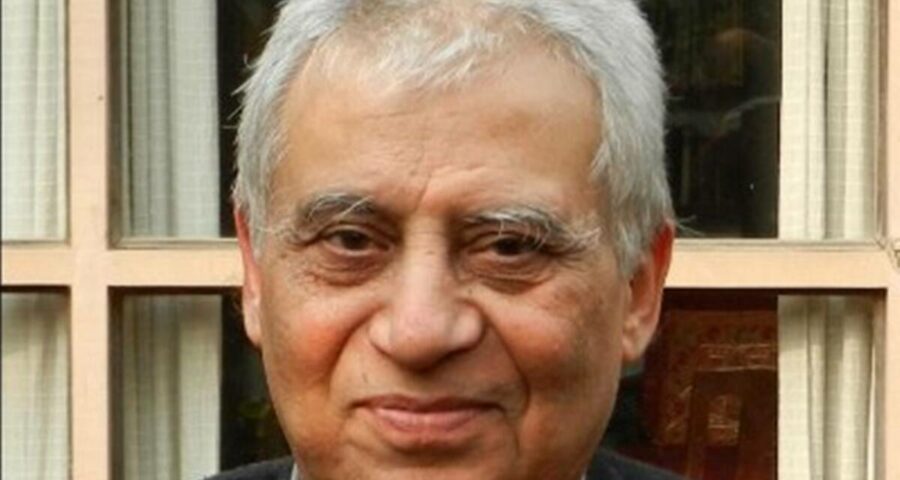

For over four decades Ganju worked among the marginalised and searched for indigenous ways to build and understand architecture

It was a rainy July afternoon in 2016. We were on a flooded, muddy road of Aya Nagar, one of Delhi’s many unorganised urban villages, that the municipal map never acknowledged. And yet, there was MN Ashish Ganju, holding out a newspaper to show the date, and taking a photograph of the pot-holed busy market street. He would send the photo to the collector and administrators. This urban sprawl on the fringes of Delhi-Gurgaon border had become his karam bhoomi for over two decades.

When he arrived here, this village largely populated by gujjars, was where migrants lived. Houses, with barely two feet deep foundation, and stacked up like ice cream bricks had no means for water, sanitation or waste management. Ganju, an architect and urban designer by training, initiated the Aya Nagar Development Project as a way to show that change was possible if you involved the community. In an interview to The Indian Express, he said, “Cities are not economic engines, they are a collection of human beings. In this century, we have seen a loss of urbanity, not the maturity of it.” He was preoccupied with enhancing the built habitat of the city, not just through structural form, but understanding the social, anthropological and indigenous capacities of its people. It directed his life-long search for what Indian architecture should be.

A teacher, mentor, and friend to many, Ganju brought vigour and freshness to understanding cities and the way we live. He passed away on May 5, due to Covid. He was 78. He leaves behind his wife Neelima, and daughters Tara, Surya and Chandani.

Trained at the Architectural Association School of Architecture, London, in the mid-60s, Ganju returned to India in 1967, but something was amiss. What he had learnt and what was on the ground were in different languages; the realities didn’t match. He was perceptive to understand that Western textbooks couldn’t comprehend the way Indians lived and cities evolved. He began teaching at the School of Planning and Architecture (SPA), New Delhi, in the early 70s, and that’s where he met architect Narendra Dengle. With Dengle, he co-authored an essay on the ‘Discovery of Architecture’ in 2014, which was a definitive view of what we had overlooked in our reading of modern architecture in India. It would become a search for understanding the history of India through vehicles of literature, visual arts, philosophy, religious studies, and the sciences.

“When he returned to India for “higher studies”, it was among people in humble environments, among villages and disenfranchised communities. In 1978, he worked with UNICEF as advisor to the government of India to build rural community centres. With him, I found a morphic resonance, since I was also working in Bengal and Bihar on rural housing. He worked with a deep conviction, he could reason and argue with open-mindedness, and build long-term associations even as he mentored numerous young architects through the TVB School of Habitat Studies, where he was founder-director,” says Pune-based Dengle. Ganju’s projects were spread across the country, from Kashmir to New Delhi, Bhopal to Port Blair. He was also on several committees with the government of India, as advisor for maintenance of the Rashtrapati Bhavan and redevelopment of the Lutyens Bungalow Zone.

Ganju’s route to architecture was always through the community he was building for. Be it the Press Enclave residential complex in Saket (1974), where he grouped houses into five blocks to keep the scale human and intimate, or the Dolma Ling Nunnery at Dharmshala (1992), which honoured Buddhist principles of living with nature, or when he sat down with the 1000 residents of G Block, Aya Nagar (2017), to build toilets in every home. “People learn from their own experiences and conversations with one another. We as designers were only facilitators,” Ganju had said.

When he co-founded Greha in 1974, with like-minded people including Dengle, architects Ashok Lall, AGK Menon, Ramu Katakam, historian KL Nadir, and artist Sheeba Chhachhi, the focus was on marginalised people in rural and urban settlements. The idea was to “develop knowledge and methodologies concerning settlement systems more suited to our history and cultural context”. His unquenching zeal to engage with the local community led to the Aya Nagar Village Development Plan. When then chief minister Sheila Dikshit visited Aya Nagar in 1999, she found the project inspirational and declared it as a model village, suitable for development.

Ganju’s “Architecture and Society” meetings that were held at the India Habitat Centre every month gave impetus to architect-academician Parul Kiri Roy. She took these ideas into her classroom and rural design studios in SPA. “The focus was about architecture as not just an object in space, but how it was fundamental to life and living. So, what is the role of the community, how did we see ourselves as part of that community, what was our role as citizens, and how did we set ourselves as architects who influence the built environment. The kind of intent, energy and drive that professor Ganju had is what got me hooked. I realised my education is incomplete, and I still had a lot to learn. With him, we worked on the Mehrauli history project. From him we learnt to keep our beliefs and hopes alive. While we always second-guessed the impact our lives and work had, he showed us what it meant to never give up. He would often say, ‘if you get out of your classroom and to the streets and dialogue with people there, you can bring about change, since you are a built environment professional’,” says Kiri Roy.

Ahmedabad-based conservationist and historian Rabindra Vasavada, says, “With his passing away, we have lost a base – a base that he developed in Greha and his home and office. He wanted to re-orient architectural education towards indigenous sensibilities, and he was quite passionate about it. He was developing proposals for universities, which would allow students to look and think in that way. And he was constantly thinking about this and working on it, through seminars, workshops, and international conferences.”

Everyone who knows Ganju testifies to his indefatigable passion for his work, be it in Aya Nagar, exploring the values of Indian architecture or his concern for waste management and sanitation in the city. For him, architecture was a deeply spiritual pursuit, where he combined his knowledge of Kashmiri Shaivism and Tibetan Buddhism.

“He was a one-person institution. Though he went through a conventional training in architecture, he was able to question it in a radical way, without any biases, and remain true to his search. Reaching his Aya Nagar studio was never easy, but once we were there, everything was forgotten in our conversations, that almost never got done in a single sitting. We always came away with new thoughts after meeting him. Whenever he said is what he stood for. How many architects do you know who live in an unauthorised colony, or fight and argue, under the blazing sun, with a PWD people over sanitation pipes not fixed right? It shows his conviction in what he believed,” says Delhi-based architect Snehanshu Mukherjee.

While his ambition for a Museum of Indian Architecture made him include people from all walks of life, architect Nirmal Kulkarni recalls his conversations with Ganju over the making of a museum. “He spoke of Greha’s projects, including the Museum of Indian Architecture, which would be a place of inspiration, where people can go and learn about themselves. For him, architecture doesn’t happen just like that. It doesn’t begin with a person, it was about daily life ultimately. He was always searching, how did the tribals build, he held discussions with sociologists, anthropologists, scientists as a way to find answers,” says Kulkarni.

Yet in all this, he never gave up on pursing beauty in architecture. Architect Henri Fanthome remembers his first visit to Ganju’s office, more than 17 years ago. The way the spiral staircase curved to the mezzanine, the roof tiles and brick walls, the light streaming in, it left an impact on Fanthome who was in awe of the busy-ness of the place, yet “nothing was out of place”. “One never saw him as trying to be a legend or an architect, he just went about doing what he believed in. I worked with him for nearly three years but I never stopped working with him. He had a refreshing spirit and an undying ability to go after what he believed in. He was the beginning of my unlearning,” says Delhi-based Fanthome.

Since 2017, Ganju and Dengle were involved in teaching the Building Beauty Program, built on the ideas of British-American architect and design theorist Christopher Alexander, in helping students understand what soulful, humane environments could be.

Source: Read Full Article