In a workshop led by photographer Varun Gupta, the process of cyanotype printing is in focus as a way to explore cheap, analogue-based, DIY ways of developing photographic images

Hours after hiding behind uncertain grey clouds, the sun is finally out. Photographer Varun Gupta is relieved. The harsh sun is a friend today, as we prepare to make cyanotype prints; photographic, analogue prints awash with a cyan-blue tinge that gives it an almost ‘vintage’ makeover.

At the Chennai Photo Biennale Foundation’s modest office in Adyar, multiple trays line up holding film negatives, papers of many sizes and brushes. For the past few weeks, the team at CPB has been experimenting with this technique before co-founder Varun decided to open it up as a workshop for the public, over the weekend.

Cyanotype was invented in 1842 by English experimental photographer John Herschel and the process was created to make copies or blueprints of architectural drawings and engineering sketches which were done on tracing paper.

A photogram | Photo Credit: special arrangement

“Two or three years after, it was adopted by Anna Atkins, who is considered the first woman photographer in the world. And, she has done an entire body of work by collecting plants, especially seaweed for making prints. She brought forth the idea that photographers can work with this process,” says Varun, who had his first interaction with cyanotypes in 2006.

Photograms (a photographic image made without a camera by placing objects on photosensitive material and exposing them to light) are what Atkins experimented with extensively, and so objects became a common component of the process, he continues. When a digital or analogue negative comes into the picture, cyanotype prints emerge. Either way, the process relies heavily on negative spaces created by the shadow of the objects in play.

Cyanotypes being exposed to sunlight | Photo Credit: special arrangement

A few sheets of paper are now being clipped on to a dark board. In minutes, these sheets will transform into photographic prints that capture the essence of this “hands-on”, analogue process of image development. Varun picks up small bottles containing ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide: equal parts of both are mixed to form an inky concoction. Individually, these two chemicals are not light sensitive and only when mixed, do their photosensitivity come alive.

“The chemicals harden when exposed to light and when not exposed, they wash away,” Varun explains. And so, when an object is placed on the painted chemicals and exposed to light, the area below the object washes off creating a negative space.

“For printing photographs, hot press paper would be ideal but for printing leaves and patterns, textured papers work very well. Anything above 200 gsm (grams per square metres) is better,” he continues. But how does one get their hands on large format negatives of their images? Varun scans the images and converts them into digital negatives to print them out onto OHP sheets.

Now, the yellow liquid is spread evenly on the clipped sheets of paper. To further give it a “handpainted feel”, Varun lets the brush loose to create patterns. Once the chemicals dry out, the negatives are stuck firmly on each sheet and pressed down.

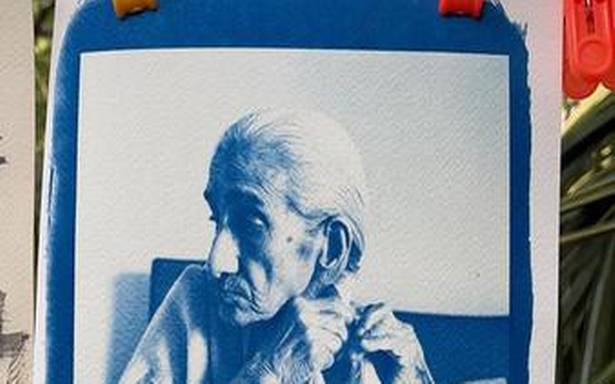

Varun Gupta | Photo Credit: special arrangement

As the sun hits the sheets, the yellow of the chemicals slowly gives away to a subtle blue. Twenty minutes later, the blue dominates as the photograph emerges as a print. To take the process a step ahead, these prints can also be toned with tea or coffee and carried out on fabric.

One of the most important aspects of cyanotype printing is that it is perhaps one of the cheapest ways to print: one can get started under a reasonable budget of ₹1,000. And, each print is likely to stay intact for 50 to 60 years. CPB is also in the process of making a kit with all the necessary tools meant for the process. “But right now, it’s in the R&D phase,” Varun quickly adds.

“The photography challenge in the digital era has been that you can buy how many ever copies of the same photograph but there is nothing unique about them. In this way, each print is unique. Then, there is an opportunity for photography to be in the space of creating original art,” says Varun, as we clip the prints to dry on a cloth line.

In a few minutes, these will be keepsakes.

Slots are open for the Sunday session from 11 am to 4 pm at CPB Foundation, Adyar. Register at shop.chennaiphotobiennale.com

Source: Read Full Article