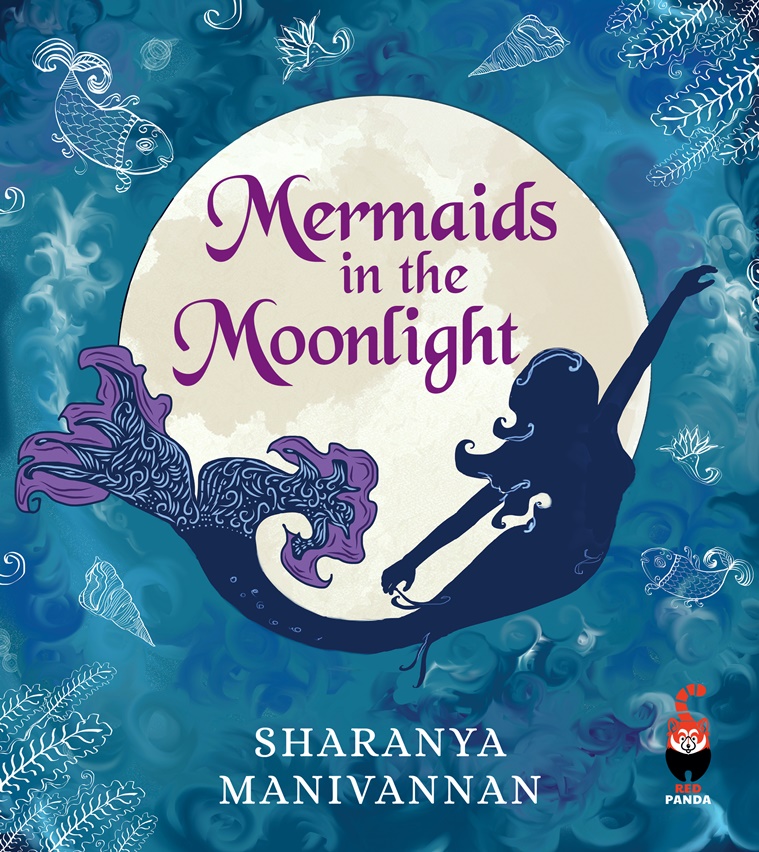

With Mermaids in the Moonlight, Sharanya Manivannan, 35, finds her way back home

Excerpts from the interview

Like The Ammuchi Puchi (2016), your second picture book for children, Mermaids in the Moonlight (Red Panda, Rs 199), too, is unusual in your choice of theme. How do you arrive at the story you want to tell, and was there anything in particular that drew you to the present narrative?

My family is from Mattakalappu (Sri Lanka). My mother would say when I was a child that there was a mermaid in her hometown, who could be heard singing in the lagoon on full-moon nights. This phenomenon is real, usually attributed to either shells or fish, and has been recorded and documented. As an adult, travelling to Mattakalappu for the first time, I was struck by how mermaid (meen magal) figures are all over the town, but there is an absence of lore about them. This folkloric void was my starting point for this work. Mermaids in the Moonlight’s companion book, a graphic novel for adults called Incantations Over Water, was my initial focus – but the children’s book took creative primacy during the pandemic.

What sort of research did this story entail?

I remember sitting on a stoop in Batticaloa on Day One of one of my meen magal research trips, exhausted to the point of tears, and asking myself why I had gone there at all, and if there really was anything I could sift out of the collective, generational losses that are also my legacy. The very next day, the path opened up and then I was in tears again. That key was the explanation for a mystery I had wondered over for a long time, on a topic that was unspoken in my family – about how my great-grandmother had been able to walk out on her marriage and live by herself, circa 1930. The Mukkuvars of Batticaloa had been matrilineal and matrilocal, at least until her generation. So she had land of her own, and the agency to begin again. In a later trip, I was able to go to where she had lived on her own too.This may seem tangential, but it isn’t – it was only once I held this key that everything began to align for me.

I asked numerous people in Mattakalappu about the meen magal as I conducted my research: fishing people, researchers, academics, activists, hoteliers and my own next of kin. They didn’t have much to say about the meen magal – but told me so much about culture, history, mystery, religion and ritual, ecology, war and poverty, gender relations and other folk tales. The folkloric void around the meen magal ceased to disappoint me once all these other ways to understand the place I come from opened up for me.

A mermaid is not that strange a thing in a place where there are revenant children and so much more. Why should a fish-tailed woman or a woman-torsoed fish be out of the ordinary? And – of course – I went into the lagoon on a full-moon night and heard those mysterious sounds for myself. After all this, I began to delve into reading mermaid lore from around the world. The international mermaid canon is vast. Writing Mermaids in the Moonlight was about selecting and threading together a set of tales that advance the narrative of a mother giving her child an inheritance of stories.

You mention in the author’s note that you hope this will encourage readers to seek out stories of different cultures and understand that stories morph with each retelling. At a time when there is an emphasis on a monolithic vision of culture, did you deliberately choose to focus on folk tales that are essentially an oral repository of cultural history?

Having a multiplicity of narratives presents a dynamic, persuasive challenge to monolithic cultural impositions. I certainly agree that they are important for this reason on a sociopolitical level. Creatively speaking, however, this is a secondary concern. I’ve worked with mythology and folklore across my books, and what usually draws me in is the pathos of a certain story, its emotional palette. Working with stories from other cultures has to be done sensitively, because there is a risk of misappropriation. I was very conscious of this, even deeply anxious at times. This is why I offer honour to the storytellers before me as the book opens, and encourage the reader to explore other versions of the stories they read therein. I have discovered that the better approach, for myself, is not to try to be authoritative but to have humility, and to weave doubt, error and ambiguity into the work.

Did the fact that you were doing both the story and the illustrations make your job easier?

I relished creating the illustrations for Mermaids in the Moonlight. Although I had been drawing and painting by hand for a long time, I only began to illustrate digitally with this book. Learning new skills as well as transferring existing skills to a new medium was exciting as well as challenging. At the very final stages of putting the book together, the illustrator in me had more say than the writer: I recall removing half the text on one page so that the words wouldn’t overwhelm the image, for example. It was very interesting to observe this in myself.

You are also working on a graphic novel for adults. What made you move to a more visual mode of storytelling?

I’ve been trying to remember why/when exactly I decided to venture into creating illustrated books too. I can’t seem to identify an epiphanic moment as such. I had been painting since my late teens, for pleasure and to make gifts for friends. Once I finished writing the short story “Conchology” in my collection The High Priestess Never Marries (2016), I knew there was more I needed to create. I certainly knew by the time I was conducting my research in Mattakallappu in 2017 that I wanted it to transpire in a graphic novel. I had been drawing so long that it felt natural, not like a major decision – although, of course, it was.

I finished writing Incantations Over Water a couple of weeks before Mermaids in the Moonlight was released, and will be working on the illustrations for most of this year. Incantations… and Moonlight… share a heart and a geography but are very different, and there is only a little overlap between the mermaid stories in both. Incantations… goes deeper into the sorrow and darkness that Moonlight… acknowledges but cannot explore. It is narrated by Ila, the mermaid that Amma and Nilavoli imagine together in Mermaids… I have written many lonely characters, but Ila may be the loneliest of them yet.

For more lifestyle news, follow us: Twitter: lifestyle_ie | Facebook: IE Lifestyle | Instagram: ie_lifestyle

Source: Read Full Article