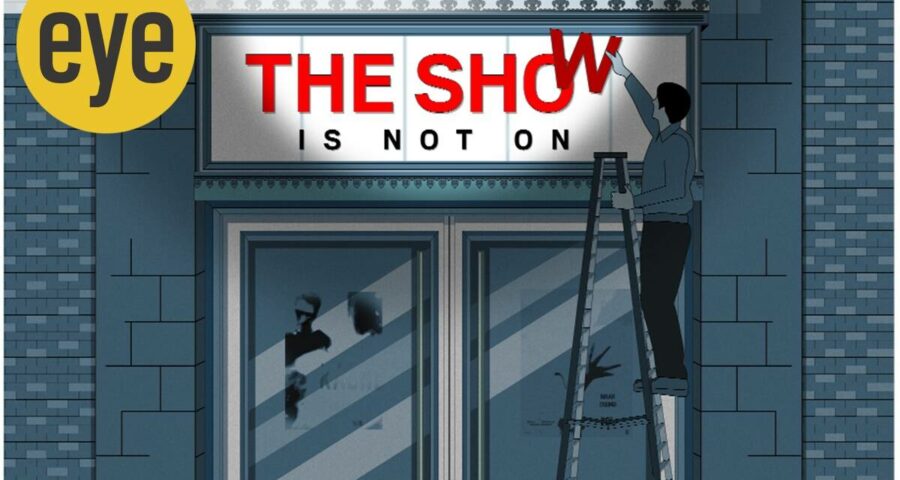

With the second wave of the pandemic, the disruption in the Hindi entertainment industry has triggered anxieties over financial insecurity and loss of livelihood

For over four decades, Rukshana Anjum, 57, has worked in the entertainment industry — first as a young junior artiste in Laila Majnu (1976) and Muqaddar Ka Sikandar (1978), and in recent times, in several television serials, including Yeh Rishta Kya Kehlata Hai (ongoing). Nearly six months ago, loss of income and depleting savings made Anjum rent out her house in Patliputra slum in Mumbai’s Jogeshwari West. With her husband Aziz ul Rahman, 57, also a junior artiste, and their two daughters, she shifted to a rented accommodation in Panvel, Navi Mumbai. Their Patliputra house fetches them a monthly rent of Rs 17,000. After Anjum pays Rs 8,500 to her landlord, the balance is used to run their household.

The couple hasn’t gone back to work since the first ban on shooting in March 2020. Though restrictions were relaxed briefly, the state government once again banned shoots in April this year, after the second wave led to a surge in COVID-19 cases. But Anjum is unsure of

returning to the sets even when shooting resumes. “My husband and I are nearing 60. With the COVID restrictions, we wonder if we will be allowed on the sets anytime soon,” she says.

Meanwhile, things were looking up for stunt artiste Geeta Tandon, who had a clutch of new projects in hand. But that was before the lockdown. Today, Tandon, a 35-year-old single mother, worries about managing school fees for her two sons, EMIs and household expenses.

They are not alone in this financial distress. When the entertainment industry in Mumbai came to a standstill in March 2020, a large number of lower-rung artistes, technicians and members of crew — who earn daily wages — were badly hit. Many of them found employment, albeit irregular, once shooting restarted. But, a large number continued to be jobless, while many others have returned to their hometowns, unable to keep pace with the expenses of living in Mumbai.

As production and business limped back to normalcy late last year, there was an obvious sense of relief. But, the second wave of the pandemic came as a rude shock. “We thought the worst was behind us. Soon after the Maharashtra government allowed shooting to resume in June last year, the production of television shows and web-series gathered steam. Around October-November, shooting of multiple films was planned simultaneously,” says Shibasish Sarkar, group CEO, Reliance Entertainment. The Hindi entertainment industry had even developed major projects hoping for a spectacular recovery. “I have always been busy, but I was never offered so many big-budget movies around the same time as I did in 2020-end. I had to let go of some,” says National Award-winning sound designer Subhash Sahoo, who has signed Akshay Kumar-starrer Ram Setu and RSVP Movies’ Mission Majnu.

Around mid-March this year, the increase in COVID-19 cases triggered concerns. By the first week of April, various entertainment bodies pressed the panic button. “If a project hasn’t gone to the floor, it is comparatively easier to stall its production. Once the shooting has started, then such disruption leads to loss of business and capital,” says Sarkar. Reliance Entertainment has several ambitious projects in various stages of production, including Rohit Shetty’s Cirkus, featuring Ranveer Singh in a double role; Neeraj Pandey’s Ishq — Not a Love Story; and Imtiaz Ali’s next with Gajraj Rao. Producer Anand Pandit, too, had to stall his plans last month for the release of Chehre, featuring Amitabh Bachchan and Emraan Hashmi. “This project is close to my heart. I will wait till we can release it in the theatres,” says Pandit, whose production, The Big Bull, released on Disney + Hotstar on April 8.

It’s not just films that have been hit. On good days, the Indian television shows fall back on scheming mothers-in-law, shape-shifting reptiles and mythological miracles to boost their TRPs. The lockdown in Maharashtra made their task tougher and forced television units to look for suitable locations in other states. Producer-actor Jamnadas Majethia, who has been shooting for the TV series Wagle Ki Duniya (on Sony SAB TV) in a resort in Silvassa, says, “The second wave caught us off guard. But, we tweaked the storyline and travelled outside for the shoot with a crew of 60.” Making the most of it, the recent episodes of the show capture the Wagles stuck at a resort with other families. Fear Factor: Khatron Ke Khiladi (on Colours TV), a big-ticket show, too has taken its contestants to Cape Town,

South Africa.

For hair and make-up artist Kiran Vanshi, 29, however, things panned out differently. When the shooting for the web-series Your Honour was stalled in Chandigarh, she had to return to Mumbai at the end of April. Now, with assignments drying up, the eldest of four siblings, worries about paying the rent for their Dahisar home.

Unlike last year, help for junior artistes and technicians came after a long wait. While Salman Khan has already provided for 25,000 workers, Yash Raj Films (YRF) launched a special initiative to vaccinate 30,000 workers, and several celebrities organised fundraisers. Hema Aziz, treasurer of Mahila Kalakar Sangh, the women’s wing of the junior artistes, has been trying hard to help members tide over this crisis. Aziz says, “There are many junior artistes who are single mothers and some have big families to look after.” Her husband, Aziz Khan, who is also a junior artiste, says, “Junior artistes don’t find employment every day; maybe, only for about 15-20 days in a good month. Whatever we earn is spent on daily needs,” says Khan, who along with Aziz had last shot for Maharaja, a YRF production, featuring Aamir Khan’s son Junaid, in early April.

Pappu Lekhraj, an agent who provides junior artistes to production houses, believes the second wave has brought more gloom and fear. “Last year, many junior artistes became security guards and delivered couriers. Some sold vegetables, while others drove auto-rickshaws. At the moment, they can’t decide whether to wait for the lockdown to end or look for other jobs,” says the 56-year-old, and adds that nearly 3,000 junior artistes are currently in Mumbai.

Junior artiste Dhanalaxmi Kapadia is in a similar quandary. The 65-year-old has hardly stopped working ever since she appeared as an “extra” in the restaurant scene in Bobby (1973) as the prying aunty who spots Raja (Rishi Kapoor) and Bobby (Dimple Kapadia) together. “I have been thinking of starting a tiffin service. But, that needs investment and I don’t have that money,” says Kapadia, who lost her husband a few years ago.

Junior artistes, typically, are used for crowds or big gatherings, often as a background of the main action. On the days they are employed, a male junior artiste gets Rs 1,000 a day, while his female counterpart earns Rs 1,200. The only other time Lekhraj saw junior artistes struggle so badly was in 1986, when the Hindi film industry went on a strike against piracy and special sales tax was imposed by the Maharashtra government.

Notwithstanding the efforts made by various associations and unions in the past, health benefits also don’t reach daily-wage earners. “Cine and TV Artistes Association (CINTAA) has over 10,000 members, of which nearly 5,000 members are on daily wages. They don’t enjoy financial security or healthcare benefits,” says actor Amit Behl, senior joint secretary of CINTAA. Though most of these actors are either trained or experienced, they are informally referred to as “one-two day actors” and often make brief screen appearances. “Actors who are regular members of a television show’s cast are insured by the producer and get COVID-19 cover. Insurance companies, however, can’t figure out how to give them the benefits even though producers have discussed this matter,” says Behl, “We are requesting stakeholders such as broadcasters, top-bracket actors and production houses to provide vaccines and rations for these supporting actors.”

For more than a year, Reliance Entertainment has been holding on to two tent-pole productions — Rohit Shetty’s Sooryavanshi and Kabir Khan’s 83 — for a theatre release. Many had pinned their hopes on these two movies to bring the crowd back to the theatres and revive the business. “The exhibitors have lost about Rs 4,000 crore since last year. The pandemic has led to the closure of 750 single-screen theatres and 500 more are likely to follow suit this year. But, once everything is normal, I see at least 20 per cent jump in the business,” says trade analyst-turned-producer Girish Johar. He, however, doubts if people would return to cinema halls in big numbers soon.

Streaming services have seen a steady rise since the pandemic began in 2020. Sarkar considers these platforms to be a “great opportunity” for producers to release their films. “If the story can be enjoyed on a smaller screen, there is nothing wrong in releasing it on such a platform,” he says and predicts a rapid growth for streaming services in the next few years. He believes these platforms would also help recover costs. “We have been getting handsome returns over and above the cost of our production,” he says. For instance, the Parineeti Chopra-starrer The Girl on the Train released on Netflix directly (February 26), while Tamil movies such as Madonne Ashwin’s Mandela (April 4) and Halitha Shameem’s Aelay (February 12) released on satellite channels and Netflix. Karthik Subbaraj-directed Tamil film Jagame Thandhiram, too, is headed for a Netflix release on June 18.

The possibilities in such streaming platforms may be a beacon for 70-year-old actor Pramod Pandey. He had challenged the state guidelines in the court last year because it restricted crew, above 65 years of age, from shoots. Though Pandey managed new assignments early this year, he is currently idle. But he’s working on a script for a web series, which he hopes will pull him out of joblessness and uncertainty.

While India battles to rein in the devastation of the second wave and apprehends the third wave, it is tough for the industry to plan its next course of action. “Right now, our focus is to keep the staff safe and get them vaccinated. Our day begins with sending out condolence messages these days. We are not thinking of resuming production unless the situation becomes normal,” says Sarkar.

Even if shooting resumes, it wouldn’t be the same. “For instance, crowd scenes have successively reduced from 1,000 junior artistes to 500 to nearly zero,” says Lekhraj, who has recently worked for under-production projects such as the Aamir Khan-starrer Laal Singh Chaddha and Excel Entertainment’s web-series Dongri to Dubai. Sahoo, too, has similar concerns. “A big-budget movie usually has 250-300 crew members, but it’ll be reduced to about 100. Each unit will be asked to hire fewer assistants,” he says.

Monsoon will bring its own set of troubles when shooting moves indoors, fear Aziz and Khan. But the two are hanging on to hope. “Kaam chalu ho jaane do, sab dheere dheere theek ho jayega (Let the production work resume, everything will be gradually all right),” they say.

Source: Read Full Article