In I Am No Messiah the actor reflects on the impact of his relief work on those whose lives he touched, as well as his own

Sonu Sood’s “Kalinga Moment” occurred on April 15, 2020, in the city of Kalwa, in Maharashtra’s Thane district. He had driven there from his home in Mumbai to help distribute the food packets he had arranged for the migrant workers who were heading home during the nationwide lockdown. But as he stood among the thousands who were making their way on foot down National Highway 48, which leads southwards to Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, he asked himself if he had done enough. In his just-released book about his Ghar Bhejo relief mission, I Am No Messiah (Penguin Random House), co-written with journalist Meena K Iyer, Sood writes: “If I had given in to the celebrity syndrome of sitting in my ivory tower and having my largesse delivered to the needy by remote control, I would never have come face to face with the trauma of the migrant workers or understood that a food packet was a woefully inadequate substitute for a ride back home.”

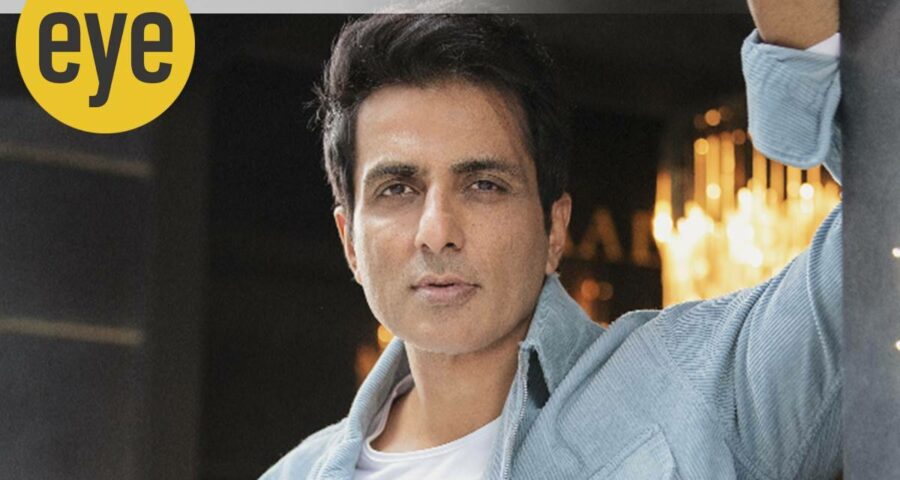

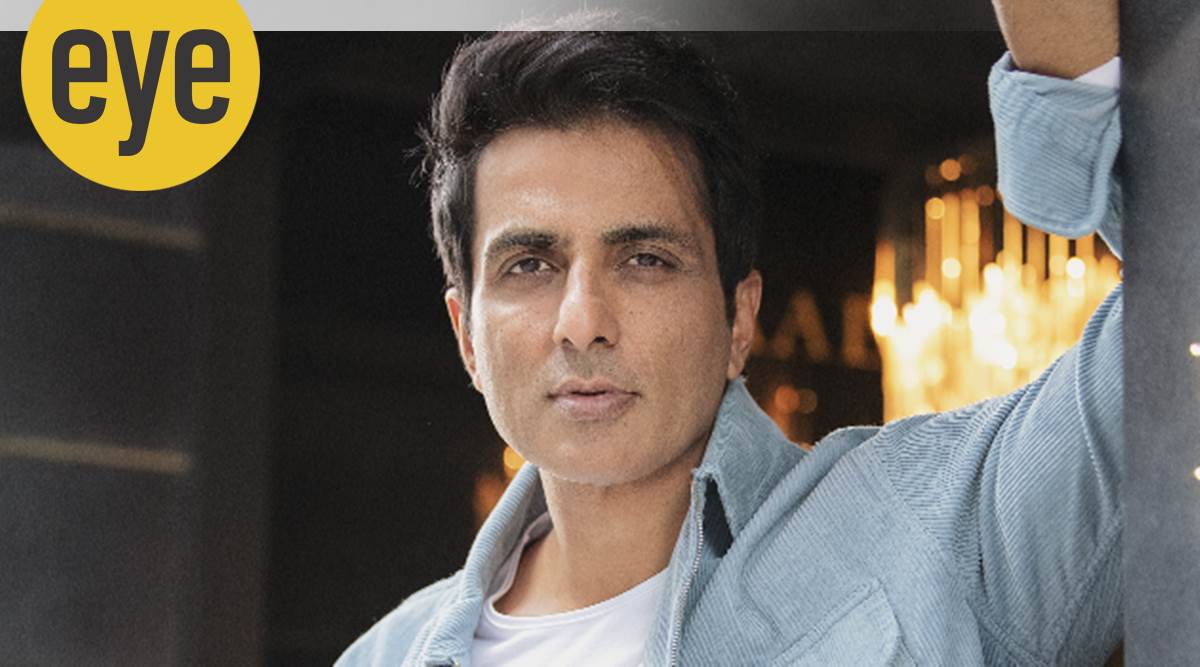

Even Bollywood couldn’t avoid the ravages of 2020. Apart from the pandemic and lockdown, which depleted livelihoods and bottom lines, the Hindi film industry was also hit by allegations of nepotism, drug abuse and more. In a sea of reputations that were bruised — and even battered — Sood, 47, seems to have emerged with a more burnished image than before. He’s been depicted as a caped superhero in cartoons, described as “a real-life hero”, “migrant Mahatma” and “asli Bahubali” and awarded the SDG (Sustainable Development Goals) Special Humanitarian Action Award by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in September. Endorsement deals with brands have materialised, too. Last month, there were reports of Dubba Tanda village in Telangana dedicating a temple, featuring a buff, T-shirt-clad bust, to the actor. But the most telling, and perhaps, with greater implications for his film career, is an incident that Sood records in his book as having happened when he returned to work on the Telugu film Kandireega 2 post-lockdown: “In the pre-lockdown script, my role had shades of grey. But in the ensuing seven months, when I switched lanes in my personal life, my humanitarian work would no longer allow even fictional villainy to taint my name.” He writes that co-actor Prakash Raj refused to grab him by the collar, as one scene required, saying “the Sonu he now knew couldn’t be treated in such an uncouth manner.” It ended with a 20-day shoot being rescheduled because Sood’s role and all his scenes had to be completely overhauled.

Born in Moga, Punjab, to English and History professor Saroj and businessman Shakti, Sood graduated as an engineer from the Yeshwantrao Chavan College of Engineering in Nagpur. This was where he met his wife Sonali and also where he first began dreaming of a silver-screen career. Sood has chronicled his early years as a film-industry struggler in great detail: the unwavering encouragement of his parents, the train ride to Mumbai in which he had to sit in the passage outside the “smelly toilet”, the many rejections and taunts from those who said he wouldn’t make it without a godfather (in another part of the book, he writes that buying a whole building in the city in 2018 was to him like a “confirmation that I’d reached a place of worth in life — an achievement that I had earned and not inherited from a big-name production house”).

Sood agrees that his relief work may prove beneficial for his career. “It’s a good thing as I wanted to play something new,” he says, “Earlier was not the right time to experiment but now the roles are refreshing and you can experiment.” But it’s an unexpected bonus, he insists. “I’m a big believer of destiny,” he says, “I believe that when you decide to help someone and go out of the way to do something good, things happen in life.”

“Becoming famous was not, as I had imagined, the end goal of my life,” he writes, “This celebrity face was imperative for the Ghar Bhejo movement to succeed, for doors to open and make things happen.” These declarations are tempered by the occasional complacent acceptance of the goodwill — and limelight — that he’s earned in the past months, such as in the surprising frankness of the chapter name, “UN Boosts the Brand”.

And, yet, philanthropy has its limits — it can’t effect lasting changes. “Philanthropy is one way to uplift life, but again for a long-lasting way, you have to structure things properly, where everyone as a team should come forward and try to do good to others,” Sood says. And, despite speculations, he adds, politics is not his path — yet. “Politics is a way to help more and more people, it will have its pros and cons,” he says, “but I’m enjoying my journey as an actor, want to continue being one, and keep on helping people.”

Source: Read Full Article