‘By birth, you are not superior or inferior to anyone.’

‘There are millions of people who want to have a casteless society. I am one of them.’

Her beautiful eyes widen for a fraction of a second. Then, her frown eases and she continues playing.

Little Vilma Naresh, all of three-and-a half-years old, is unware that she might be headlining a change in India.

A change that is both vital and needed and one that could redefine the character of this country.

And that change, one her parents are determined to herald, has caused an upheaval in her life that the little one is yet unware of.

She had been rejected by several schools in Coimbatore, where they live because her parents, Naresh Karthik and Gayatri, are unwilling to tick the caste and religious boxes on the admission application form.

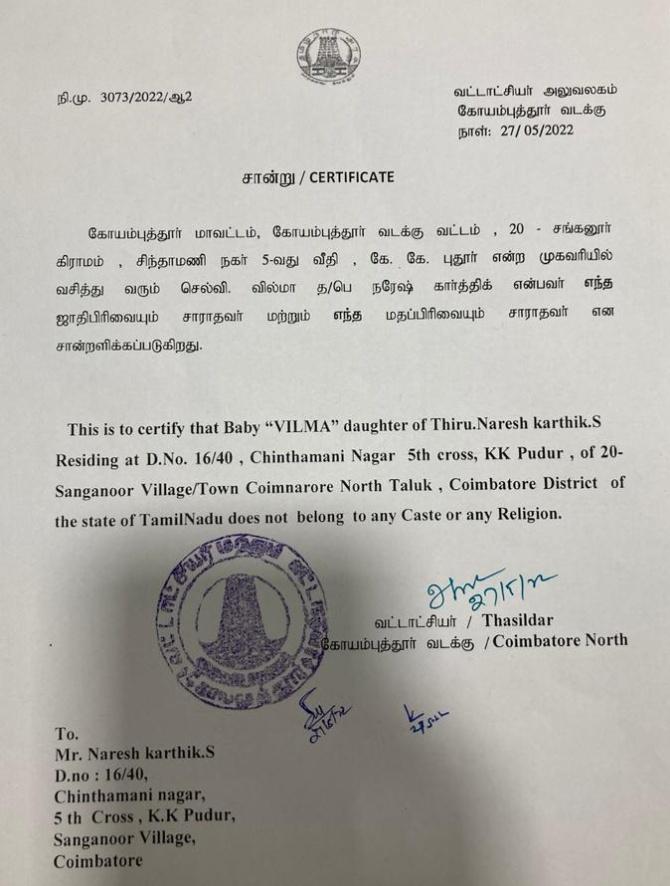

They have, as a consequence, obtained a ‘no caste, no religion’ certificate for their daughter.

This is the second such certificate issued in Tamil Nadu. The first was obtained by Sneha Parthibaraja in 2019.

Naresh Karthik, 33, is a businessman dealing in graphic design. He was born and brought up in Coimbatore and has completed his BSc in psychology and MSc in criminology.

Naresh, who married his wife Gayatri in 2014, also runs an NGO called Seedreaps Educational & Charitable Trust.

Caste and religion, he tells Rediff.com‘s A Ganesh Nadar, has not caused problems in his life; in fact, both his wife and he belong to the same religion.

Why then did he feel the need to get a ‘no caste, no religion’ for their daughter?

His NGO, he explains, helps victims of crimes like domestic violence, abuse, rape, drug abuse and acid attack.

In the 10 years since it came into being, it has supported children of prisoners and juvenile delinquents struggling to integrate with society after being released from remand homes.

The aim is to help children complete their education.

The NGO — which is supported by a few corporates and gets some funds from the government as well — pays their school/college fees.

“We look after them till they get a job; we also help them find a job,” he says.

So far, they have helped 1,153 children, of whom 378 have found jobs.

Though they operate nationwide, most of children they support are from Coimbatore; a few come from the rest of Tamil Nadu and some other states.

Explaining the process, he says, “We help these children get admission in regular schools. On the admission application form, in the section meant for caste and religion, I tick ‘Other Castes’ which is an unreserved category.”

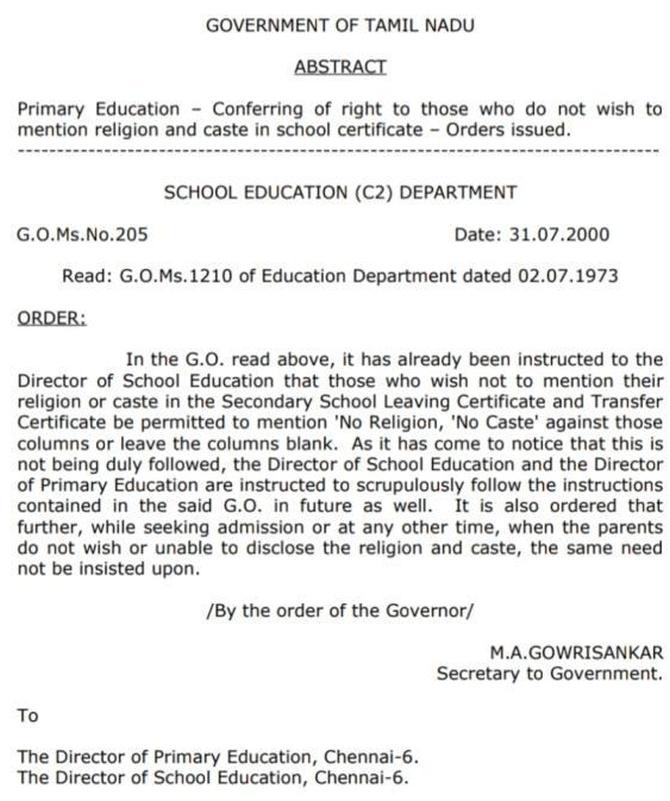

While doing so, he would also submit a copy — attested by an IAS, IPS or chief educational officer — of the Tamil Nadu Government Order No 1210/1973. A lawyer had told him about this order, which states that if you don’t want a reservation, you don’t have to mention caste or religion during the school admission process.

“We hope for a casteless society,” he says. “I believe in Ambedkar, (revolutionary Tamil poet Subramania) Bharatiyar and the Tirukkural (this classic Tamil language text contains 1,330 couplets by the saint-poet Thiruvalluvar, each of which is a life lesson). The Tirukkural gives your life more value than any religion. Caste is a by-product of religion.”

Naresh also believes religion restricts the rights of women.

“By birth,” he says, “you are not superior or inferior to anyone. There are millions of people who want to have a casteless society. I am one of them.”

“In my daughter’s case,” says Naresh, “I decided to get her a certificate.”

He explains why.

When it was time for their daughter to be admitted in kindergarten, the schools they applied to demanded a community certificate. He requested that they give him 10 days to get it.

After checking with 20 schools, he found out none of them knew about the 1973 government order.

That’s when he decided to meet Coimbatore Collector Dr G S Sameeran. The collector listened to what he had to say and asked him to meet the north Coimbatore tahsildar, who proved to be helpful as well.

Naresh was asked to submit an affidavit stating he didn’t want to restrict his daughter to any caste or religion. He was told that, once this certificate was submitted, she would permanently ineligible for any privilege based on caste or religion.

He submitted the application to the tahsildar. Six days later, the certificate was in his hands.

Based on this certificate, Vilma got admission into kindergarten without having to reveal her caste and religion.

Vilma’s mother Gayatri shares her father’s views. But his parents, and hers, took time to understand why their children were insistent about this issue.

Karthik smiles, “They wanted to know why I did it, why I was making a fuss about it. They advised me to go with the crowd. They also wanted to know how their granddaughter would be treated in school as a result.”

As far as his other relatives, and society in general, were concerned, he says, “Ten per cent feel it is a statement against religion and caste; they don’t like it. Five per cent are indifferent. But the majority are with me; they have told me it is a commendable thing to do.”

Talking about the school, he says, “You learn everything in school. That’s where you grow as a human being. I want my daughter to grow up without the baggage of caste and religion.

The advantage of letting go of reservation, he says, that it will be available for someone who really needs it.

In fact, he welcomes reservation for the economically weaker section of society.

When his daughter is older, Naresh plans to talk to her about his heroes. About

He will talk to her about Thiruvalluvar. Ambedkar. Bharatiyar. Periyar.

“She will understand why I got her this certificate,” he says with pride.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article