In a globalised world, where no food feels foreign and tastes are transforming rapidly, how does the debate over authenticity in recipes play out?

Italy was in an uproar. Unpardonable liberties had been taken with the pasta carbonara, one of the most iconic preparations from the southern European nation. Authentic carbonara from Rome is made by tossing hot pasta (often spaghetti) in a sauce made with eggs and pecorino Romano cheese, along with freshly-ground black pepper and guanciale, the latter made by curing the jowl meat of pigs. But a sacrilegious recipe in The New York Times had substituted unremarkable bacon for the robustly-flavoured guanciale and used mildly sweet and nutty Parmesan, instead of the saltier and tangier pecorino. Worst of all, the writer of the recipe had used tomatoes, an unthinkable addition to a simple but delicious pasta preparation that even eschews garlic and parsley.

Last week’s outrage over the NYT recipe, which began on Twitter, would have been amusing, like all other such food-related outrages, but for the fact that this question of authenticity in food is one that has begun to crop up now with greater frequency and urgency than ever before across the world.

Given how globalisation has shrunk the world, this ought to have been par for the course, especially among urban dwellers, whose relative financial security has made them more cosmopolitan than ever before. We eat waffles for breakfast, ramen for lunch and quesadillas for dinner. We are as familiar with kimchi as we are with achaar, and churros are just our favourite new way of consuming more chocolate than is good for us. No food really feels foreign, because the world is our salad bowl.

But is the cost of this cosmopolitanism being paid in a flattening of identities and cultures? Is meaning being eroded from that one word — authenticity — which has the greatest currency in the world of food? And what place does “authenticity” have in a world that is rapidly adapting to new conditions, including availability of resources, transformation of tastes and the emergence of new trends? For something to be authentic today seems impossible when even the ingredients that go into one cup of caffè mocha can’t be traced to a single origin. Creative expressions like cooking are far more promiscuous. To go back to the example of pasta carbonara: what if one can’t afford guanciale and pecorino, but still wishes to partake of the creamy deliciousness of carbonara?

“You can’t make a Kashmiri gustaba with duck meat. If you do, please be sure to mention that this is your innovation and explain why you decided to do it. There is no harm in being inspired by a dish and making your own innovations. That is part of the creativity of cooking,” says Delhi-based chef Manish Mehrotra, who runs the restaurant Indian Accent. In other words, he says, own the creative liberties you take with a classic while also respecting it. At the same time, Mehrotra believes that the demand for authenticity, especially with food traditions that are as poorly documented as Indian food is, can become unreasonable. “How do you define what is ‘authentic’? What is an ‘authentic’ kaali dal or meen moilee? This is the biggest problem with our cuisine; there are so many innovations, discoveries and inventions, but so little of it is properly documented. It’s not like how (French chef and culinary writer Auguste) Escoffier wrote books that set down the standards for French recipes which were then tested and validated by generations of chefs,” he says.

Even when culinary traditions are better documented, creative liberties will be taken, he says. “Take carpaccio, an Italian dish. If you were to eat the traditional version, it would have to be thinly-sliced raw beef. But, over time, chefs have used the word ‘carpaccio’ to refer to anything that is thinly-sliced and served raw, like pineapple or salmon,” says Mehrotra.

The question of authenticity touches a raw nerve, particularly when it becomes a matter of cultural identity. It then transforms into a question about appropriation which asks: who has the right or the authority to talk about a certain kind of food, especially when it is rooted in a very particular culture? In May 2020, this question was at the root of the outrage about former NYT food columnist Alison Roman, who was accused of building a career in food without acknowledging how much she had appropriated from other cultures. Critics pointed to her use of ingredients like turmeric and coconut milk without ever mentioning their origins and her development of recipes such as the chickpea stew, which was clearly based on South Asian and Caribbean chickpea curry recipes.

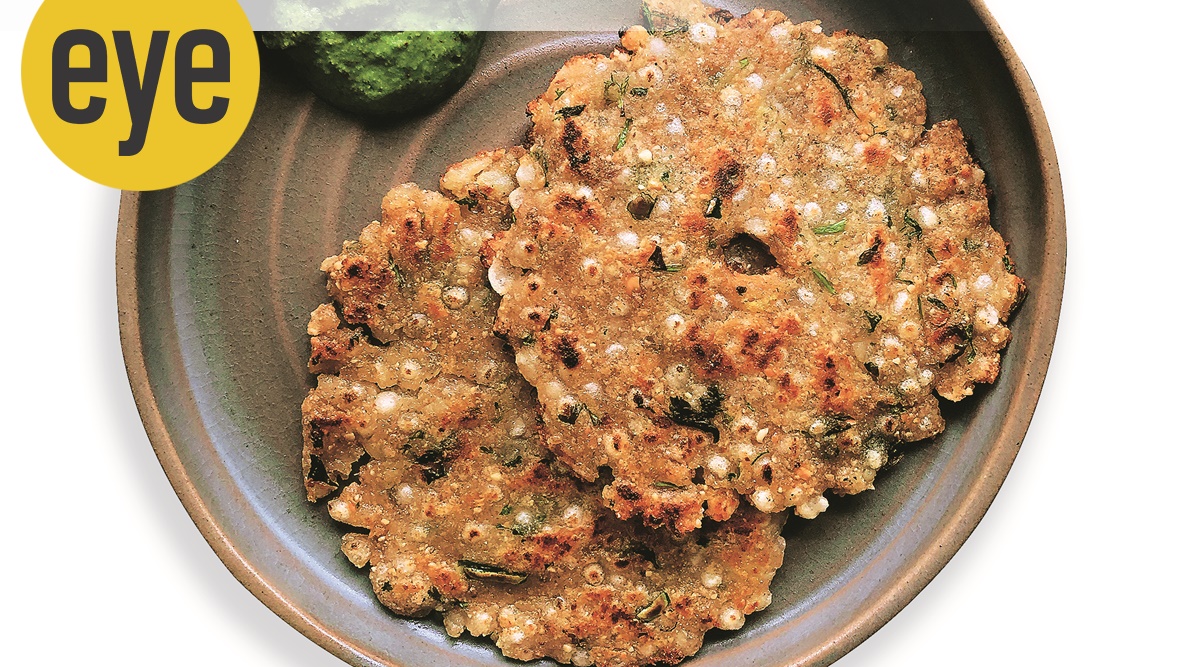

Author and culinary consultant Saee Koranne-Khandekar has been grappling with this question of authenticity because of her work in regional Indian cuisines. The necessity of wider reflection became clear to her last year when she came across a recipe for the Maharashtrian speciality, sabudana thalipeeth, by a popular food content generator on Instagram. “It was just a besan chilla with some sabudana pearls sprinkled on top,” she says. What upset Koranne-Khandekar was the assumption of authority. “It was definitely not how Maharashtrians make sabudana thalipeeth, so they shouldn’t have called it a Maharashtrian recipe,” she says.

Creative interpretations have a necessary and exalted space in food. At the same time, Koranne-Khandekar points out, “authenticity” can be discussed only with respect to a certain socio-cultural context. She takes the case of the popular eggplant preparation known as bharli vangi as an example. “It is a pan-Maharashtra dish. But because Maharashtra is such a big state and has such varied topography, bharli vangi changes from place to place. What you get along the coast would be very different from what you get in Nagpur. Caste is also a factor. You won’t get the same bharli vangi in a Hindu Brahmin house and a Hindu Kayastha house or a Maratha house,” she says. The element of time further complicates the matter. “Eggplant is one of the oldest vegetables cultivated in India, whereas tomatoes came to us fairly recently, in the 16th/17th century. If you go to the average Maharashtrian household, you’ll find eggplant dishes that use tomatoes. How did this happen? We once used tamarind and kokum as souring agents and ingredients like peanuts, coconut and sesame seeds as bulking agents. But now tomatoes are used as both souring and bulking agents. They are available throughout the year and the average person finds them affordable. So can you say that the food they make using tomatoes is inauthentic?” she says.

Authenticity in food isn’t simply a matter of politics or even semantics. The need to label something as “authentic”, especially something as emotive as food, is hardwired in us, says Krish Ashok, author of Masala Lab: The Science of Indian Cooking (Penguin, 2020). “It’s easy to step back and laugh when people get outraged over ‘inauthentic’ food, but this emphasis on ‘authenticity’ is a natural outcome of our relationship to food and the way we experience it. Our perception of flavour in food is multidimensional — there’s the aroma and the mouthfeel, but also the sight of food, the context in which we eat it,” he says. To understand this, he points us towards neuroscientist Gordon M Shepherd’s Neurogastronomy: How the Brain Creates Flavour and Why It Matters (Columbia University Press, 2012) which explains how the human nose and brain work together to create indelible mental “images” of the flavour that we love or loathe. Shepherd quotes the saying, “Patriotism is a longing for the food of our homeland”, writing that it, “expresses a loyalty to our home country based on the flavours of the food we were brought up on.” He adds, “Even in our age of globalisation, when our daily fare may include dishes from other lands…the particular combinations we learn while growing up are part of our national identity.”

Identity, whether it is connected to one’s nation, community or family, is emotional terrain that is best navigated with caution. That is why, Ashok says, we find people insisting that this bowl of sambar or that plate of biryani is the only authentic version. “Our experience of the food feels very real, and we do believe that our good taste is shared by everyone. This is particularly strong in places like India, where our cuisine is not only segregated by region, but also caste. So, you end up building a flavour preference,” he says.

At the same time, one can’t be dismissive of the power dynamics that are inherent in issues of food. In contemporary food media, this is most evident in who gets to talk about a certain kind of food and profit from it, and who doesn’t. Like Koranne-Khandekar, Ashok, too, believes that the best way to acknowledge these dynamics is to acknowledge the history and socio-cultural context they are rooted in. “In India, for example, if we bring peasant and Dalit cuisines to the forefront, this matter of authenticity become very important, because of the history that lies behind them.”

Food just may be the most dynamic expression of our collective and personal histories. Koranne-Khandekar says, “There is a community of Maharashtrians who migrated to Mauritius many generations ago. They, too, make amti, a preparation that is very common in Maharashtra. But toor dal (pigeon pea), which is what we use here, wasn’t easily available in Mauritius then, so they started making amti with chana dal. It may seem inauthentic to a Puneri Brahmin, but is it really so?”

Writer and culinary consultant Rushina Munshaw Ghildiyal puts it this way: “As a chronicler of cuisine, I think it’s important to document ‘authentic’ food. If you tell me that this is how you cook a particular dish in your family, I want to document that accurately. But when I cook it in my kitchen, at home or in a restaurant, I might make changes, because finally, I want that dish to be eaten.” There is another important factor we fail to consider when we insist that recipes be by-the-book. “We never take into account ‘taste memory’, and this makes a lot of difference even if two people are cooking the same thing, with the same ingredients, in the exact proportions,” she says.

Finally, however, every dish comes down to what is available and what tastes good to the people who will eat it. “The pizzas made in Ahmedabad, with all the chilli and sugar and the pile of Amul cheese on top, may make an Italian cringe, but that’s what the locals want to eat. If you serve an ‘authentic’ carbonara to an Indian, they may be put off by it. The person who made that controversial carbonara probably enjoyed it, and that’s what matters,” says Munshaw Ghildiyal.

Source: Read Full Article