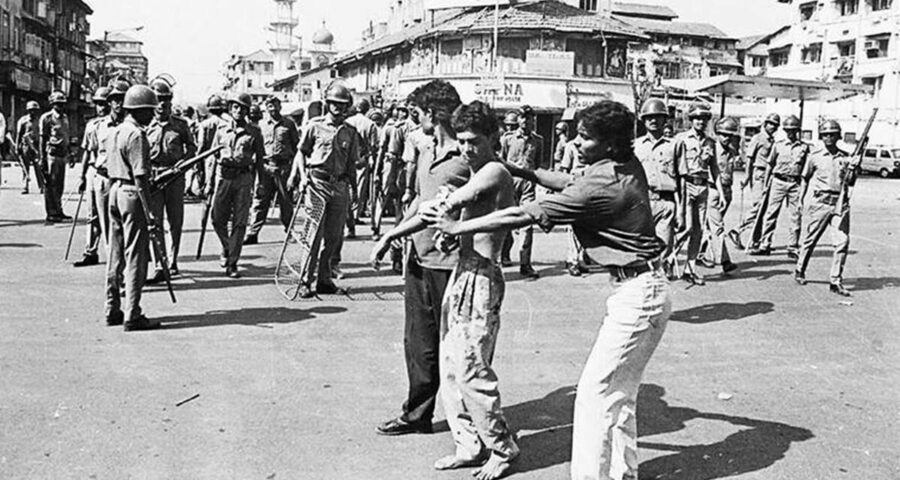

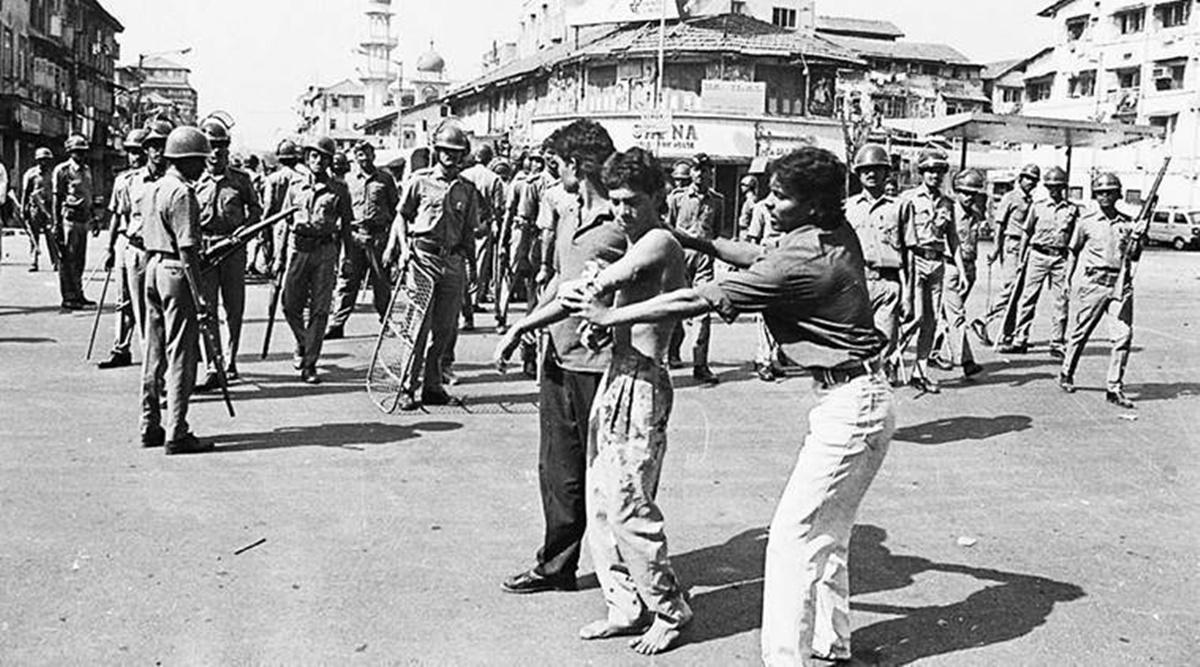

After the Babri Masjid demolition on December 6, 1992, Bombay, like many other parts of the country, had experienced riots, violence and curfew. Christmas and New Year passed uneasily.

January is when my friend’s home was burnt down, all her baby photographs forever destroyed. This was in Charni Road. She once opened up about it and since then has maintained silence. January was when we left home. Let me rephrase that. January was when we felt forced to leave our home. In an apartment block in South Bombay. It was Bombay then. The year was 1993.

After the Babri Masjid demolition on December 6, 1992, Bombay, like many other parts of the country, had experienced riots, violence and curfew. Christmas and New Year passed uneasily. There was a lingering air of gloom and disbelief at what had happened. But we believed the worst was over.

We first heard about the election lists circulating in neighbourhoods with Muslim names conspicuously identified. The newspapers reported on mobs entering buildings and pulling residents out. Many residential buildings removed the boards listing names of flat owners. Some even had residents patrolling the grounds. Our apartment building decided to take out only our names from the board below. The only Muslim residents of A-wing. The B-wing had no such problem: There were no Muslims living there. My parents tried not to get upset about this in front of us but I recall my mother calling up the building secretary and asking most decorously how this was allowed to happen. When you are the only ones, you keep your voice low. One morning a chand-sitara (moon and star) was scrawled in chalk on the wall next to our door. We had been marked.

Soon after, one night, my father said, “It’s time to go. Tomorrow I will come home from office. After lunch, we will leave. Carry one small bag each, no suitcases.” We packed a few clothes and books. My parents bundled up our passports and bank books. They locked up other important documents in the Godrej cupboard in the room furthest from the front door. I wondered. Would the marauders get to that last? Would they be caught before they reached there?

It struck me that I should carry the rough draft of the essay I was writing for admission to a college abroad. And maybe a weapon of some sort. A bidri envelope opener? The metal knuckleduster that had proved useful against harassers in the bus? More. Something more. I went to the kitchen to search. I ignored the knives, though thinking back they should have been my first port of call. But the newspapers by then had been sick with news about stabbing and gun-shot wounds. My eyes settled on my mother’s red chilli powder bottle. I seized it. Wrapped it in a shirt and put it in my knapsack. Perhaps, it evoked the memory of Smita Patil using chilli powder against an oppressor to great effect in Mirch Masala. Many years later, it struck me that we only used mild Kashmiri chilli powder, not particularly noted for its fieriness.

Twenty-eight years have passed since that date but I cannot forget.

How we left that afternoon. Where we went. How we spent time. What went through our minds and hearts. Why we returned some weeks later to that same flat in that same building. How we continued to live in the city we had called home since before my birth. These are stories for another day.

Our names never again appeared on the name-board on the ground floor. My father retired from the job that gave us the flat to stay. My voice still trembles when I recount to someone, usually very rarely, that month and those days. Sometimes, tears I thought I had long left behind appear in the corner of my eye. That was Bombay, India, January 1993.

It might have been yesterday.

The writer is a Mumbai-based journalist, researcher and co-author of Why Loiter

Source: Read Full Article