Understanding the dilemmas facing a growing dystopian world through a prescient 1971 Oscar-winning Italian film

Global democracy appears to be in decline with the rise of populist, majoritarian, neo-fascist, or right-wing authoritarian governments across the world. Experts from the fields of social and political psychology have theorised the inner workings of authoritarian minds. Essentially speaking, such personalities are bullies, but they are bullies with political power at their disposal. Recent events have shown that many of the newly elected authoritarian leaders, apart from being undemocratic in spirit and anti-minority in orientation, also deliver poor quality of governance. Yet, why is there such little collective reaction from citizens, especially those supporters of the regime who otherwise may have joined protests, voted against the regime or at least turned vocal?

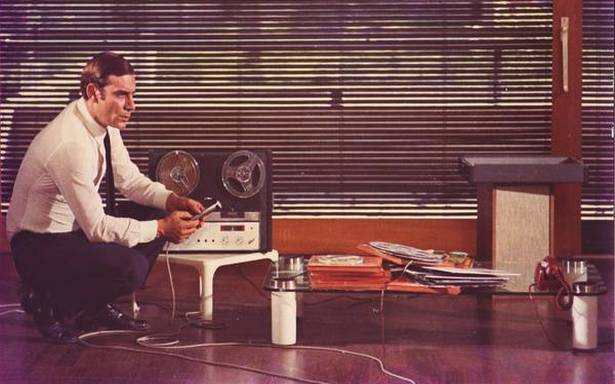

A piece of art that bridges the gap and best describes the psychology and the pathology of such regimes and their tactics, exemplified in the personalities of their leaders, is Italian filmmaker Elio Petri’s Oscar-winning feature film, Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion 1970).

The plot

The film opens with an unnamed police officer (later identified only as “Inspector”) committing a murder and planting, very carefully, a number of clues at the site of the crime. Throughout the movie, multiple flashbacks also tell us that the Inspector is a loner and in a relationship with the murdered woman. The two of them are shown to be indulging in playful enactments of famous murders and torture games. The woman taunts him about his sexual prowess, and his authority as a policeman. During one of the later flashbacks, it is revealed that he suspects that she is sleeping with a young radical from the same building. This fills him with rage and he kills her on the last day of his job as the head of the homicide unit. The next day, the Inspector takes over as the head of political/security affairs while he continues to assist the new chief of homicide in the murder. He directs the investigation repeatedly to the clues left by him, and admonishes his former colleagues for not following through the trails found during the process. This entire exercise is his way to assure himself that he is “above suspicion” and despite clear evidence against him, he cannot be touched by the law enforcement.

In the climax, the Inspector enters a dream sequence where he is confronted by his colleagues and superiors about his crime. Interestingly, in this surreal dream sequence, his colleagues and superiors deny his involvement in any crime. The Inspector appears to possess a different body language during this entire episode —he approaches his colleagues and seniors in complete submission starkly contrasted with his masochistic and overbearing personality throughout the film. Similarly, his colleagues and seniors treat him like a child, even caressing and patting him. All the evidence that he presents against himself is rejected by his colleagues and they go on to celebrate this event. While they leave, the Inspector comes back to his true self again and warns them about the intimate enemy that they need to fight together. The movie ends with him regaining his senses and the actual arrival of the superiors of the establishment to interrogate him, while the tension builds.

The climax of the movie is open-ended. In the anticipatory climax from the vantage point of the Inspector he not only finds a “closure” to his “experiment”, but also manages to regain his towering position among his peers. In an alternative interpretation, the climax is the culmination of his constantly degenerate mental state. The Inspector seems to have lost his authority as well as charisma, and potentially awaits a favourable judgement from the regime for his services.

There are at least three core insights that can be drawn from the movie to understand our contemporary political context.

‘A dystopian world’

The movie presents to us a dystopian world where every person is a suspect and possibly an enemy, not only of the state but of the entire social order. The state and its instruments keep an eye on everyone and the distinction between public and private lives are increasingly blurred. The political/security department possesses a named file for every person, including its own employees in the police. The Inspector’s inaugural address to the political division as it new chief is revealing and disturbing, for its uncanny similarity to the world around us. The Inspector begins by pointing out that he has been chosen as the new chief because, “at this time, political and non-political crimes have become nearly indistinguishable.” He goes on to clarify this point in even simpler terms: “underneath every criminal person lies a subversive individual and underneath every subversive individual there hides a criminal.” The political question of the times is presented thus: “The exercise of freedom is a constant threat to the establishment…freedom makes every citizen a judge and prevents us from doing our jobs”. Therefore, the Inspector asserts, “repression is our vaccine, repression is civilisation.”

‘Unquestionable leader’

The Inspector is sick, self-obsessed, vindictive and insecure. But he knows that his actions bear complete impunity because of his powerful position in a tightly-knit security state and his subordinates’ absolute and meek capitulation to authority and, by implication, to him. During many instances in the movie, all evidence leading to the Inspector, including his finger prints, shoe prints, photos, etc., is sought to be brushed aside or even justified by his former and current colleagues.

We get further clues about the megalomaniac character of the Inspector during one of the flashback sequences where the woman and him are role-playing and enacting police torture. The Inspector tells the woman: “I represent power, the law.” At another instance, he tells one of his colleagues, “I want to affirm the concept of authority in its purest form”. What about the outside world, then, one may ask? The Inspector mocks a former colleague when the latter talks about arresting the ex-husband to assuage public sentiments: “You are a bureaucrat, public opinion frightens you.”

There is an almost complete unanimity about who the enemy is: the young radical, who is sought to be implicated in the murder of the woman, and others like him, are described as “socially and politically dangerous, subversive and fanatical”. It is as if for the entire department, and clearly in the case of the Inspector, personal vindictiveness and collective political hatred for free individuals become indistinguishable from each other. In one of the rare moments of self-reflection during the derisory climax, the Inspector shares his motivation to kill the woman: “Each day in her company revealed my incompetence as a human being”.

The climax is farcical but an opportunity for the Inspector to clarify his deep motivations. In the dream sequence, his superior tells him, “you have had a dissociation, a neurosis”. It is important to appreciate the Inspector’s considered response: “However, it is a contracted illness due to the prolonged use of power. It is an illness common to a lot of powerful persons.”

‘Service to the nation’

The Inspector’s self-aggrandisement project is intertwined with grand conceptions of his purpose as the chief of homicide, and later political/security divisions. The personal and the political for him meld into one as he commits the murder out of spite for the woman and her suspected young radical lover. But this very murder is crucial for his understanding of himself and the system he deeply believes in. For the system to work in the way he imagines it, his actions must be above question. Since he is the embodiment of power, his position must be completely beyond and above any suspicion. Questions are not only detrimental to the institution of power, they are its death-knell. If there is even a little doubt in the minds of those who work under it, the institution of power breaks down.

On the other hand, the evidence is always in front of the entire department but rather than following the leads, his colleagues find excuses to exonerate him. When he is unable to bear it anymore, he confesses his guilt in writing and gives it to the new chief of homicide division. Finally, he waits to be rewarded for his “mistakes” so that he can get back to punishing the enemies of society and the state.

In lieu of a conclusion

An interesting aspect of the film is that authoritarianism is shown as a psychological and mental illness that needs to be recognised as such. The Inspector fantasises about killings, violence, and absolute domination, and is, in fact, disappointed when his “experiment” as part of a part-real, part-fictitious fascist utopia runs counter to his expectations. He is a person who hates free individuals and freedom as an active concept.

The Inspector, in the eyes of the viewers, keeps giving in, with more grave mistakes at every turn. For the protagonist, however, these are neither gaffes nor careless slips but well-considered series of actions to resolve the classic dilemma facing an authoritarian individual and/or a system: will someone rise up, implicate the leader for his crimes and call his bluff? That single action by an ordinary citizen can be disastrous for the regime. Since this is always a possibility, shall the leader leave this open or shall he take it on, face-to-face by actually conducting a live experiment? The film shows how it is done by authoritarian leaders and that they do still win the game, just like our Inspector in his anticipated climax. Can we blame the Inspector alone? Please note that the entire edifice of this fascistic dystopia is built upon its definition of free and thinking individuals as enemies. The climax also shows the complicity of the entire regime, when it becomes imperative for all the colleagues and superiors of the Inspector to exonerate him from his crimes because the outcome otherwise will be detrimental for the system.

The good news is that just like the Inspector, populist authoritarianism or neo-fascism consistently gives clues and possibly incriminating evidence against itself. But who will join the dots to see through the vacuity of the regime and especially its leader?

Awanish Kumar is British Academy Newton International Fellow, University of Edinburgh

Source: Read Full Article