Rajeev Malhotra writes: Many of the ideas that she planted during her time in the rural development division of the Planning Commission grew into policies over time

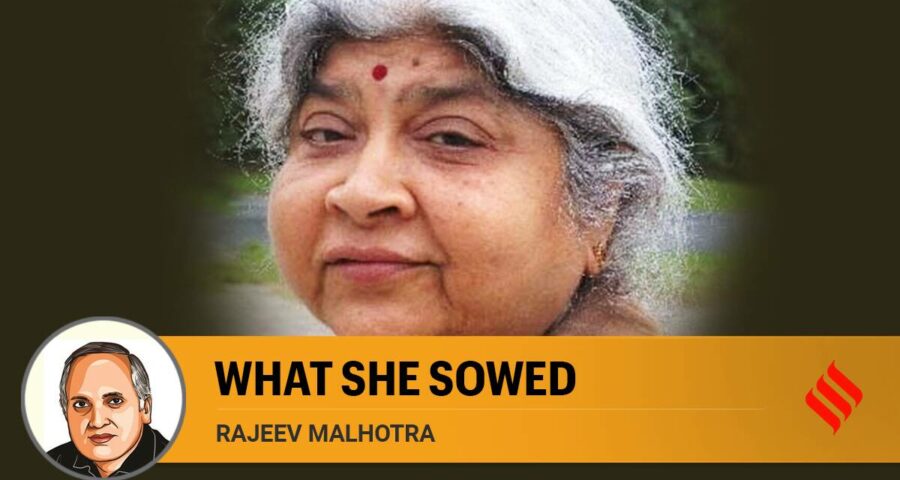

Rohini Nayyar, a well-known economist, former principal adviser at the erstwhile Planning Commission and one of India’s foremost authorities on rural development passed away on October 24, stoically fighting illness and the consequences of the negligence of some doctors who attended to her in the last few years. She lived a full life as a professional, an ideal companion and anchor to her husband, Deepak Nayyar, a doting mother to her sons, Dhiraj and Gaurav, and as a compassionate person who cared for all, but particularly for those less fortunate. Her heart was in the right place, and she had a mind that was fearless, always engaging with issues that mattered, professionally as well as socially, never hesitating to take a stand when required.

She had a unique career trajectory. After completing her Master’s degree in economics from the Delhi School of Economics, where she also met Deepak, Rohini joined the IAS in the Uttar Pradesh cadre in 1969, serving in Agra, Kanpur and Lucknow. She left the service within a few years to be with her husband at Oxford, where she did her BLitt in economics. In time, she wrote her DPhil thesis on rural poverty in India at the University of Sussex, a pioneering institution in development economics. She then chose to combine her academic specialisation with her interest in administration and policymaking by re-joining the Government of India as adviser in the Planning Commission in the late 1980s. For almost two decades, until 2005, she headed the rural development division at the Commission, rising in rank from joint secretary to secretary. Such a long stint in one position is rare in the government system and it made Rohini’s domain knowledge indispensable to a succession of governments who were all keen to make an impact in rural India.

Many policy ideas that were seeded at her time in the rural development division of the Planning Commission were implemented over the years. She was an early advocate for rationalising centrally-sponsored schemes at a time when such schemes were proliferating. In the 1990s, she believed in the need for a rural employment guarantee scheme, an idea which the UPA government wished to implement in 2004. As fate would have it, she was due to retire in 2004 shortly after the UPA took office but she was asked to stay on in the Planning Commission for a year after her retirement to help design the flagship NREGA.

Her analytical contributions were equally significant. In the 1980s, her estimation of rural poverty and analysis of inter-state differences, based on quantities of food and other necessities consumed, rather than household expenditures, was a pioneering original contribution. In the 1990s, her estimation of district income along with Vinod Vyasulu greatly enriched the literature on rural development.

There is one instance, fresh in my mind, which reflects the person and the professional that Rohini was. In 1998-99, the Planning Commission was taken to task by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance for not having prepared a human development report for the country, when even Bangladesh had one. The Commission was directed to prepare one in a limited time. The initial thought was to outsource it. I thought of this as a great opportunity for the Planning Commission. However, being a relatively junior officer at that time, I needed an adviser-level person to back the project. I approached Rohini, although I was in a different division, to provide her leadership to the proposed project. It took a couple of minutes to brief her and she was ready to walk to the secretary’s office to take responsibility on our behalf. We set up a team under her leadership to complete the task and presented the report to the prime minister and Parliament in the stipulated time frame.

Not once during the preparation of the report did she betray any sign of concern, as the buck stopped with her. She would often come to my office and share a cup of Darjeeling tea, a fondness that we both shared. It was her way of encouraging us to do a good job.

Her legacy will survive through all the lives she touched.

This column first appeared in the print edition on November 9, 2021 under the title ‘What she sowed’. The writer is a former civil servant and professor at Jindal School of Government and Public Policy

Source: Read Full Article