Re-evaluating what students have learnt, tracing those who’ve dropped out and offering support to the ones who’ve faced tragedy or hardship are some of the ways in which schools can make a safe space for students

Written by Garima Agarwal

“What do you miss about your life before the lockdown?” This was my ice-breaker as I spoke to girls from Delhi’s government schools during a phone survey, around this time last year. Answers were usually some wistful variant of “I miss my school, teachers and friends. I am bored at home and I can’t study this way.”

Delhi’s public education system was relatively quick to respond to the first national lockdown in March 2020. By the first week of April, lectures were available online for class 12 and text messages or IVR technology were used to assign activities to younger students.

Government will and the state’s high mobile penetration made this possible in urban Delhi, but students in public schools elsewhere may not have been as fortunate. As we prepare to reopen schools across the country, some learnings from this survey and recent research are worth highlighting. My findings are based on a phone survey I conducted with 210 girls enrolled in grades 8-12 in Delhi’s government schools during July-October 2020. This covers the first seven months of school closure. While the situation may have changed since then, the devastating second wave leaves little hope of improvement and we should prepare accordingly.

Students have been out of regular school for nearly 15 months now. If they were itching to go back just a few months into the lockdown, surely they’re desperate now. There is evidence that a 14-week school closure following the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan put affected children behind by about 1.5 years despite compensation for economic loss. This may be associated with lower earnings in adult life. Figuring out a safe way to reopen schools is an urgent need.

In my sample, all but one girl had internet access. While almost a fourth of the sample had personal devices, the rest were able to use a family member’s phone to study. Almost everyone reported being offered some form of online education from school at the time. While WhatsApp was being used near universally to share content and assignments with teachers, about two-thirds had live classes with their own teachers through various video conferencing platforms. Just under a third were attending online lectures made available by the state Department of Education. On average, these girls were spending between 2-3 hours on schoolwork everyday. While much lower than a usual school day, this is not bad given the circumstances.

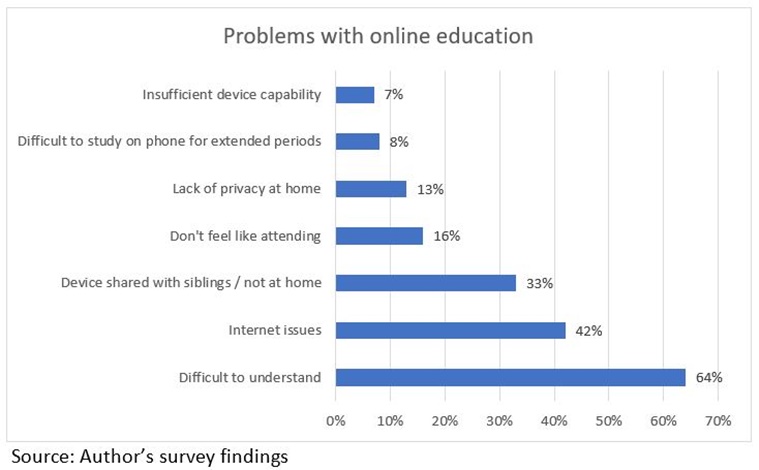

But making material available is only one side of the story. Around three-fourths of the sample was facing issues with online education. Out of these, 64 per cent felt it was difficult to understand and clear doubts without physical classes, 42 per cent mentioned internet issues and 33 per cent said their device was shared with siblings or was not available at home. Other problems included low motivation to attend online classes, lack of privacy at home to attend classes, difficulty in studying with phones for extended periods and insufficient device capability.

A grade 12 student from South-east Delhi said, “There is only one phone in the house. My sister has (online) ITI classes and my brother has regular classes from his RPVV school. For a month the phone was not working so I could not start studying.” Another girl from South-west Delhi said she had stopped attending classes as she did not understand them: “You cannot stop the class and ask doubts. The syllabus is proceeding very fast and there is too much homework.” Some girls also shared that completed assignments posted on class WhatsApp groups were often copied by other students. For one girl, the only place her phone would catch network was the terrace of her house. Even if made available from school, online education may not translate into learning for many.

Was private tuition able to make up some of the access gap? While almost three-fourths of the sample was attending tuition before the lockdown, this was slashed by half at the time of interview. Most of those who weren’t going said their teacher was unavailable or their centre was shut at the time. Moreover, hardly anyone not attending tuition before joined subsequently. The share of students reporting any issues with online education was marginally lower amongst tuition takers versus non-takers. Therefore, tuition could potentially have addressed some problems, but wasn’t widespread enough to make a real difference at the time.

The first national lockdown affected families in various ways, making it even harder for students to focus on education. A large majority experienced lower household earnings and some reported job losses as well. Eighty per cent of respondents admitted to feeling stress at the time of the interview. Of these, as many as four-fifths were concerned about disrupted education, one-fifth mentioned financial problems and one-tenth were uncertain about their future. These numbers are telling, and the second wave may well have made things worse.

What should we keep in mind as schools reopen? First, learning gaps need to be identified and plugged. Students have gone through an entire grade and even been promoted without proper assessment. As they come back, their knowledge should be re-evaluated, and we should find ways to teach at the right level. Simply maintaining the status quo could compound the learning gaps to insurmountable levels. While challenging, after-school programmes with mentoring and peer support may be useful. Parents and older siblings may play a big role here, as suggested by the last Annual Status of Education Report (ASER 2020) as well.

Second, student retention could take a big hit as the long disruption has broken momentum for many. This is especially problematic as girls transition to secondary school. Anecdotal evidence suggests that if not engaged in education, teenage girls are perceived to be at risk of unsuitable attention. Economic and cultural pressures might push such girls into low-paying jobs or early marriages. One respondent shared her fears regarding her father’s plan to relocate the family to their native village, what it would mean for her education and perhaps marriage. As schools reopen, it is essential to keep track of those who do not return. The sooner these leakages are plugged, the better are the chances of long-term retention.

Finally, major tragedies have ravaged families during this time. Relatives have been lost prematurely and many have gone through unprecedented stress and anxiety. These effects will take a long time to go away, if at all. For those coping with the death of a parent, institutional financial and emotional support will be critical for continued learning. This support could manifest as fee waivers, scholarships, help navigating bureaucratic procedures and counselling for mental health.

The decision on when to reopen schools remains uncertain given concerns regarding an impending third wave, effects on the under-18 population and vaccination for kids. Hopefully, schools can reopen to full strength soon, and when they do, let’s be ready to provide the safe spaces our next generation needs as it recovers from this setback.

Garima Agarwal is a PhD Candidate in Economics at the Delhi School of Economics and teaches Economics at Shri Ram College of Commerce. Her doctoral work looks at constraints to schooling for adolescent girls and related policies.

Source: Read Full Article