Public intellectuals who frame the ideological antipathy between the RSS & Co and Jawaharlal Nehru in the light of Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination and Hindu Raj alone, miss the point by a yard, argues Shaan Kashyap.

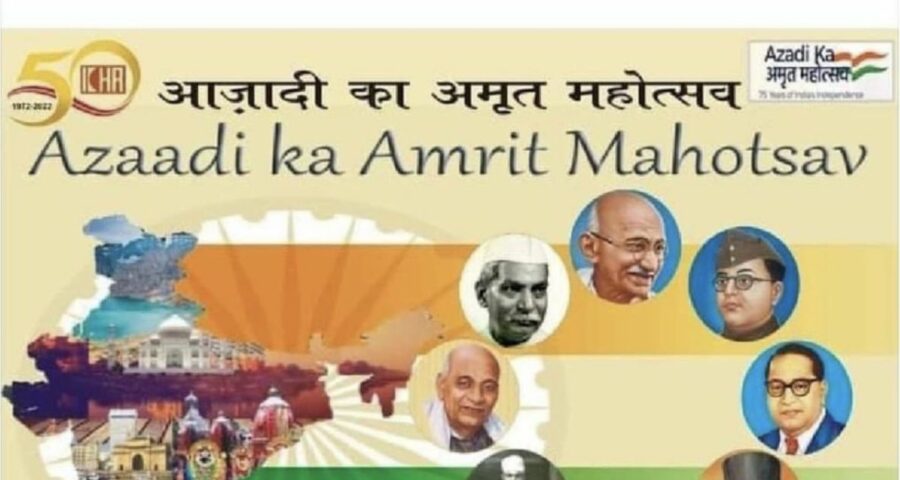

The missing picture of Jawaharlal Nehru from the Indian Council of Historical Research’s ‘Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav’ poster is not an act of omission alone, but a circumvention which undermines the unremitting argument over why the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh hates Nehru and the Nehruvian.

Public intellectuals who read the complications between Nehru and RSS & Co entirely as ideological antipathy are on the mark, but they fail to take a stock of the changing nature of their raison d’etre.

Purushottam Agrawal in his recent piece in The Print (external link) does the same. His reading of the problem as ‘Hindutva institutionalising pettiness’ and how Nehru ‘understood and explained best the mortal danger that their (RSS) and the Hindu Mahasabha’s ideology posed’, and thus he being at the centre of attacks, is correct but, I fear, incomplete.

This argument now crumbles under its own burden of conventionality and reiteration.

The foremost peril of this argument is the implied suggestion, though certainly unintended, is that the other icons of the freedom movement who feature on the poster, viz, Mahatma Gandhi, B R Ambedkar, Subhas Chandra Bose, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Rajendra Prasad and Bhagat Singh, didn’t understand and explain the threats of religio-cultural fundamentalism of the Hindu Mahasabha and RSS.

A scholar and public intellectual of the stature of Purushottam Agrawal would certainly never argue so. And that is what necessitates a rejoinder to suggest that Agrawal’s reading of the poster through missing faces is knotty.

The poster should be read in the light of ‘presence’ and not ‘absence’. And that would better explain the absence of those like Nehru, Maulana Azad, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, and others whom Agrawal importantly mentions.

I will emphasise here on Nehru alone, because his absence is much greater than just an ideological conflict over Hindutva and secularism-pluralism.

Nehru is deemed ‘un-Indian’ by RSS

In 2018, a catalogue of the annual convention of Prajna Pravah held at Ranchi, Jharkhand, carried images of many freedom fighters on its cover, and even provided their brief biographies inside. It had some hundred entries on the makers of modern India, classified under various heads as politics, culture, society, arts, and sciences.

That catalogue had a glaring omission in Jawaharlal Nehru. This writer happened to ask a Sangh sympathiser columnist why Nehru was missing from among hundreds of entries. His unpretentious response was, ‘Nehru is an un-Indian thinker. He didn’t have a Bharatiya chitti (ideal soul).’

Prajna Pravah is an umbrella organisation of hundreds of ‘think-tanks’ which provide the ideological fodder for millions of Sangh workers, and their various affiliates. As its mission (external link), the organisation makes a distinction between ‘Indian’ and ‘Western’ worldviews suggesting, ‘Western view of life sees separateness of mind-matter, faith-reform, man-nature, religion-science, etc’.

It further adds, ‘It is an irony that independent Bharat, instead of learning any lesson from the Western experience and following the basic inspiration of her own freedom struggle, has been blindly following the Western model’.

The idea is simply spelt out. Every grand idea which goes into the making of the ‘Nehruvian consensus’ has been marked as ‘Western and thereby ‘un-Indian’ by RSS thinking minds. To them, Nehru was never Indian in his thinking, and he led India to follow a ‘Westernised mechanistic civilisation’.

This argument was long in making. If one starts examining the earliest responses of Sangh ideologues such as Deendayal Upadhyaya in the pages of Panchjanya and Organiser to the Nehruvian impetus after Independence, it becomes clear that the RSS deemed Nehru as ‘un-Indian’.

‘Apart from temperamental weaknesses and hesitancy, there is a fundamental error in the thinking of the prime minister’, Upadhyaya wrote (external link) on August 28, 1961, in Organiser, on the issue of the merger of Nagar Haveli and Dadra in the Indian Union. He alleged that Nehru only thinks in the framework of the Government of India Act of 1935 or the India Independence Act of 1946.

The implication, thereby, was that Nehru even in the 1960s was still guided by a ‘colonial mentality’, and not the ‘Bharatiya chitti‘, a charge which the RSS kept repeating without fail, except in one moment of truce.

Moment of truce, lost!

Public intellectuals who frame the ideological antipathy between the RSS & Co and Nehru in the light of the Gandhi assassination and Hindu Raj alone, miss the point by a yard.

They forget the meeting between (then RSS Sarsanghchalak Madhav Sadashiv) M S Golwalkar and Nehru in August 1949. These two meetings at Teen Murti House were celebrated by Organiser as ‘Two Men of Destiny Meet: A Happy Augury for the Future of Bharat’.

The September 6, 1949, issue of Organiser even declared: The Congress and the Sangh have a more or less similar vision of the Bharat as it should be’.

Next month, in November 6, 1949, issue championing Nehru’s US visit, the Organiser edit exclaimed, ‘Every Bharatiya is proud’ of the ‘honours showered upon’ Nehru.

However, this enthusiasm and truce didn’t last long because Nehru punctured the attempts of RSS cadre to enter the Congress despite some key leaders such as Acharya Kriplani and Govind Ballabh Pant being votaries of the idea.

The subsequent rise in the attacks on Nehru and his ‘un-Indian’ vision in the mouthpieces of RSS, and the Nehru government’s clampdown on them didn’t help the case.

The case of Brij Bhushan vs The State of Delhi was exemplary in this regard, when in April 1950, the Organiser publisher and editor Brij Bhushan and K R Malkani went to the apex court to get the pre-censorship order quashed.

The subsequent and sustained attacks by the Sangh on Nehru, be it on the planned economy, construction of ‘temples of modern India’, deeming secularism as ‘pseudo-secularism’, and whatnot, continued.

Not only this, Organiser also invited columns from key Gandhians such as Vinobha Bhave, J C Kumarappa, Acharya Kriplani and N V Gadgil to criticise and condemn the Nehruvian planned economy and development, arguing how it is ‘Western’ and ‘un-Gandhian’.

However, despite these serious charges, the ‘Indian-ness’ of Nehru and his faith in the civilisational values were indubitable.

Even a cursory glance at The Discovery of India (1946) tells someone how Nehru couldn’t imagine the prospects of a modern nation-State without paying tributes to the culture of synthesis and amalgamation of different civilisational currents which made India what it was.

Nehru, in fact, had great scope in his views on Indian civilisation that he could talk about Hinduism, Materialism, The Epics, History, Tradition, and Myth, and Buddha’s Teaching in the same breadth.

Swami Vivekananda finds one of the most befitting tributes of his moment in the works of Nehru when Nehru calls Vivekananda ‘a kind of bridge between the past of India and her present…’

Therefore, while the judgement that Nehru best understood the communal designs of Hindutva ideology as a contemporary is fine, the attacks on him by the adversary have been designed differently.

The RSS & Co do not blame Nehru for having banned the organisation after the Gandhi assassination or for their electoral marginalisation in the early decades. They argue that Nehru led India to a Western model of development, essentially, because Nehru was an ‘un-Indian’ thinker.

We will have to set our minds to this more vicious and webbed allegation in the context of ‘Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav’.

Shaan Kashyap is a researcher of modern Indian history at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi.

Source: Read Full Article