Water is going to be a central part of the government’s 2024 election campaign.

And Gajendra Singh Shekhawat’s work will be crucial for it.

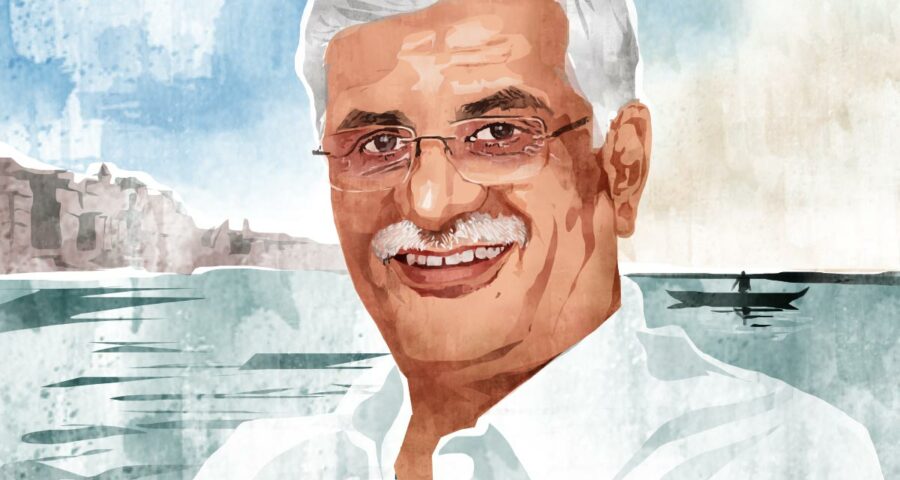

It’s been raining all night. I’ve had to tippy-toe through rivulets ankle-high to reach Jal Shakti Minister Gajendra Shekhawat on a day jal is out in its full shakti.

“Land! Blessed land!” I cry out to myself as I navigate to the pavement, sodden and muddy, making my unsteady way to the gate of his residence on Akbar Road in Lutyens’ Delhi.

My chappals squelch and squeak.

He emits a startled squawk when he sees me, asks his aides to turn down the air conditioner and confides that he took the Metro to return home from the airport the previous evening.

“At least in the Metro, you know exactly how much time the journey is going to take. Stupid to use the car in weather like this,” he says.

He apparently uses the Metro a lot.

Unconventional. But then everything about Shekhawat, 53, is unconventional.

His managers complain with affectionate exasperation that he throws security to the wind while meeting people.

No matter what time of the day or night it is, if people are waiting to see him, he will go out of the gate to receive them and escort them inside.

He belongs to Jodhpur, the land of the Thar desert where men are men.

But he loves cooking and is a dab hand in the kitchen where he can create masterpieces — Chinese food, continental… “kucchh bhi banwa lo (order anything and I’ll make it),” he says.

“When I’m around, my friends never have to worry about food,” he grins.

I believe him. He’s also a keen sportsman, a national level basketball player.

He also has a wide and deep understanding of IT applications.

He whips out his phone and, ignoring the somewhat hunted look in my eyes, proceeds to take me through the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) dashboard that can offer you a tour of the JJM’s work down to the block level.

This is technology application at its best, and it does not differentiate on the basis of caste, religion or community.

“If somebody in the village complains, ‘You haven’t done anything for us’, all I have to do is take him through the app.”

Breakfast arrives. It is vegetarian, healthy but delicious.

Thin roundels of bread toasted crisp, smeared with spicy potato filling: crunchy on the outside, buttery on the inside.

Hot rawa idlis with sambar and chutney. Poha. Fresh fruit.

A Jodhpur speciality, called Misri ki roti or bina paani ki roti — basically a baked sweet biscuit. And sweet masala chai, robust and full-bodied.

He helps himself to something that looks like bikaneri bhujiya.

You can take a boy out of Rajasthan but you can’t take Rajasthan out of a boy, I think to myself.

He tells me about his constituency. It is on the India-Pakistan border and before it was fenced, families would often visit relatives in villages that lie on the other side without being aware they were crossing the border.

That was the situation till the 1970s.

But smuggling from Pakistan started in the 1980s, gold and silver first and then acetic anhydride, a crucial chemical in the making of heroin.

As Pakistan experimented with fundamentalism under General Zia-ul Haq, conversion activity could be seen in border villages as well.

“It was immediately visible in the clothes people wore: The dhoti and the pagdi was replaced by the dadhi (beard) and the skullcap,” he says.

Shekhawat became active in student politics in the 1990s.

He motivated young men and women from local villages to form border security squads.

Highly experienced desert trackers, basically cattle herders in an area where it would rain once in three years, called ‘paagi‘ who could track pug marks, were encouraged to share their trade with these squads.

This, in turn, became an unofficial, informal league of counter-terrorism experts who shared information with the Intelligence Bureau and Military Intelligence.

“Young men and women were given a stipend, both to study and to become informal border volunteers. Then the fence came up and now, you have the challenge of drones,” he says.

I steer him back to his ministry — which is vast.

The water resources ministry has been expanded to include some elements of sanitation, clean Ganga mission, urban water, rural water, river interlinking…

More recently, he has got an additional responsibility — Green Hydrogen, which is going to be India’s ultimate weapon to brandish at those (including a former US president) who rail that India is among the ‘dirtiest, most polluting’ nations in the world.

Shekhawat’s mantra, which he repeats during the course of the conversation, is “ownership”.

People must have ownership of resources.

Whether it is the target of providing every home with piped water by 2024 or ensuring the quality of drinking water, the model is — the people must get involved.

And this should be via monetary contribution as well as management of the resource.

So, while state governments have been provided financial outlays to create drinking water infrastructure, the gram sabha and panchayat contributed 10 per cent towards the cost of infrastructure, with scheduled caste villages contributing 5 per cent.

The infrastructure is maintained at nominal cost, which is recovered from the users.

Gujarat, he says, has already done this and Himachal Pradesh and Haryana are in the process.

Paying imposes a sense of responsibility.

He reacts with vehemence to the election promise of the Aam Aadmi Party in Goa, for instance, that drinking water will be free if AAP comes to power.

Shekhawat concedes that river interlinking is not without peril.

But he also flags the problem of floods and drought, and says some solution must be found.

The linking of the Ken and Betwa between Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh has been endorsed by both states.

This is going to be the test case — not just of the technical aspect but also the politics of river interlinking.

“Nal se jal” (a tap in every household) is all very well,” I ask him somewhat belligerently, “but the water also has to be fit to drink.”

Every urban household will install a reverse osmosis plant even if they can’t afford anything else, I inform him. He is patient.

“Did you test the water in your taps before you decided to get an RO?” he asks.

He says testing water quality is his primary mission.

Initially in every Indian district, but gradually at every block level, groups of women are being trained to test water quality.

It is a simple, uncomplicated kit that gives you a breakdown of water quality almost immediately — in itself the result of a challenge put to hundreds of start-ups that have produced several innovative kits, all linked to an IT grid that can be monitored online.

Impurities like arsenic, mercury and lead can be detected instantly and can be treated, he says.

I try to imagine what will happen to the bottled water industry when that happens.

Shekhawat’s passion for his work is evident and it is clear he can talk on the subject for hours.

But I have another question: Politics and the issue of leadership of the Bharatiya Janata Party in Rajasthan, the tussle between him and former chief minister Vasundhara Raje Scindia.

He is, again, unconventionally candid.

He doesn’t deny rivalry — “politics is about competition”.

But reports of differences are also exaggerated.

His primary target, understandably, is the failure of the Congress-led state government, currently in power.

There’s a pause. Someone has come to see him. He is also a bit pensive.

His mother, in her late 70s, has survived Covid, but has a chronic lung condition that prevents her from breathing normally.

There isn’t a lot modern medicine can do.

We part, however, on a note of hope.

Water is going to be a central part of the government’s 2024 election campaign.

And Gajendra Singh Shekhawat’s work will be crucial for it.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article