His thoughts rooted in feudal instincts must be rejected while his rationalism must be affirmed

(Written by Najmul Hoda)

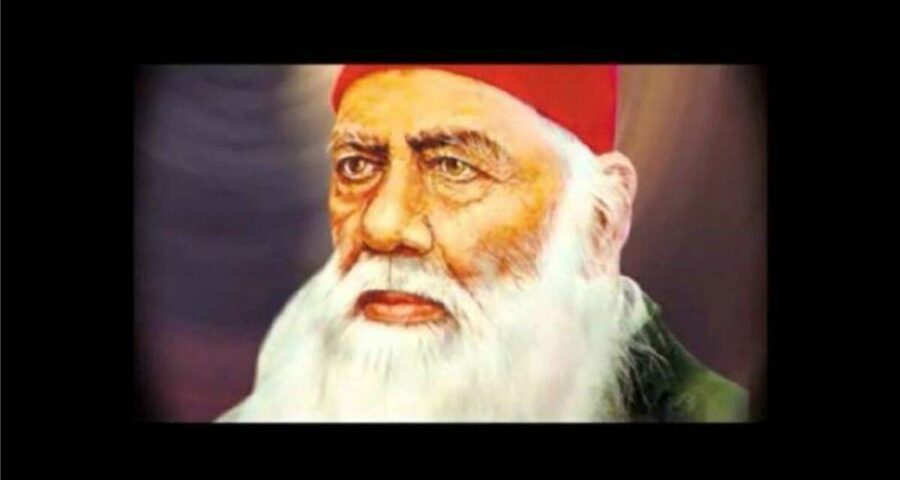

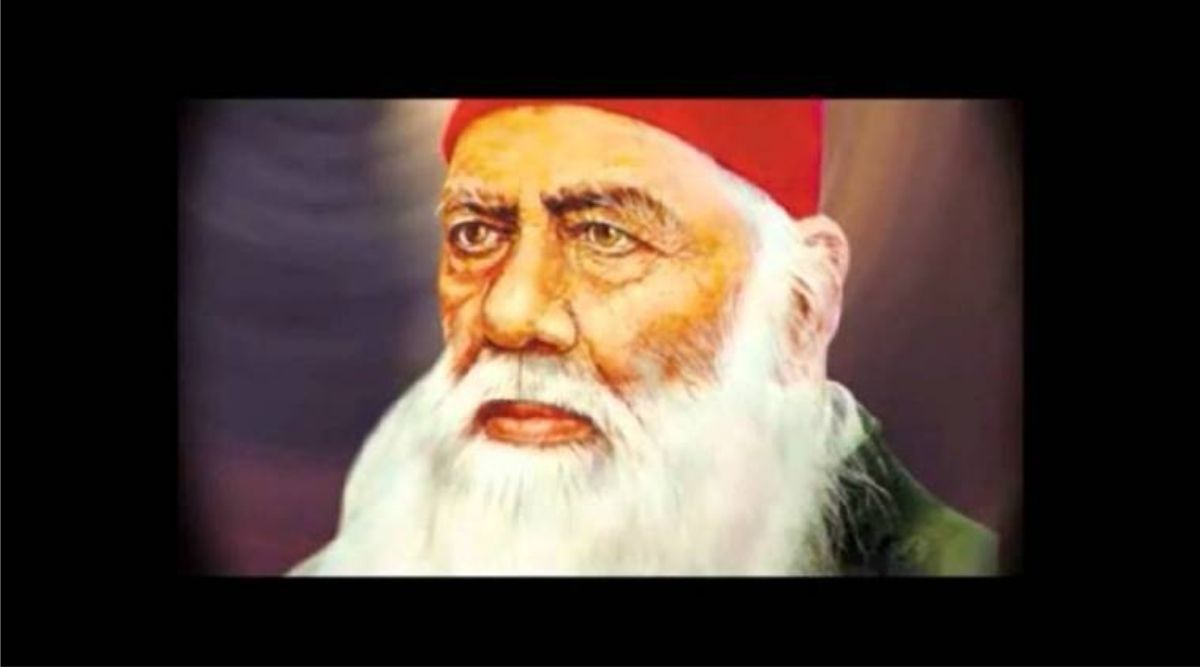

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan (1817-98), popularly known as Sir Syed, the founder of Muhammadan Anglo Oriental (MAO) College, which went on to become Aligarh Muslim University, is regarded by Pakistan as its ideological progenitor for propounding the politics of separatism that crystallised into the two-nation theory. This not only lead to Partition but continues to haunt the politics of the three countries that emerged from this dismemberment. Yet, in the official narrative of India, he is celebrated as one of the nation builders. In 1967, the Publications Division of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting brought out a Khaliq Ahmad Nizami-authored monograph on him under the ‘Builders of Modern India’ series. Further, in 1973, India released a postal stamp in his honour, and another in 1998 to commemorate his death centenary.

Sir Syed lived in a period of tumultuous transition when the old was dead but the new was not yet born. Negotiating one’s way through its uncertainties would entail many a contradiction that remained unresolved. A recent biographer of his, Shafey Kidwai, writes, “His books and articles simultaneously discuss contradictory views, and any attempt to draw them into a single narrative is destined to fail.”

The Pakistani narrative is about how his legacy actually unfolded, and the Indian one is about what could have been. A conciliatory Sir Syed would say, “Hindus and Muslims are the two eyes of the beautiful bride that is Hindustan. Weakness of any one of them will spoil the beauty of the bride”. But, his combative persona would fulminate, “Is it possible that under these circumstances two nations — the Mohammedans and the Hindus — could sit on the same throne and remain equal in power? Most certainly not. It is necessary that one of them should conquer the other.” If the Sir Syed of “the two eyes of the bride…” came runners up to the one of “It is necessary that one of them should conquer the other”, it was because of his obsessive passion for the preservation of the interests of the former ruling class to which he belonged.

Sir Syed was primarily a rationalist thinker who tried to update religious thought in Islam per the scientific mode of thinking. He also tried to find unity between Islam and Christianity — the religion of the British rulers — as an antidote to the religious animus his people bore towards them. This two-pronged endeavour, however, was aimed at the restoration of the privileged status of his class, the ashraf — the descendants of the Muslim conquerors who derived social prestige and entitlement to political supremacy from their much-flaunted foreign origin. Despite their centuries-old domicile in India, they shunned assimilation as a religious creed, maintained a stranger’s indifference to the history and culture of the land, and formulated their relationship with the country in strictly political terms. They described themselves as ashraf and translated the word aristocracy as ashrafiya to reflect their sense of the self. As landed gentry, they were spread all over India but were mainly concentrated in the areas adjoining Delhi, particularly the western Uttar Pradesh. Though everyone had suffered in the wake of the rebellion of 1857 as the British unleashed a reign of terror, the sufferings caused to this class distressed Sir Syed the most. Everything that he said and did, henceforth, was aimed at the rehabilitation of ashraf as “the aristocracy of the country as in British as in Mughal times” (Peter Hardy, 1972, Muslims of British India).

This landed bureaucratic gentry, those seasoned in what David Lelyveld calls the Kachehri milieu in his masterly Aligarh’s First Generation (1977), needed modern education to reinvent themselves as the ruling elite. A modern college was the proposed panacea. But modern education seemed too Christian to them. So, Islam had to be interpreted in such a manner as to make it congruent to modernity. But the ashraf rightly perceived modernity to be antithetical to their traditional interests. Therefore, Sir Syed’s religious ideas were to be kept out, and religious instruction was to be handed over to maulvis from Deoband. Sir Syed agreed to this since the enlightenment that he envisioned was instrumentalist, aimed at readying his class for re-powerment. If re-powerment could come without enlightenment, it was still a good deal. However, an instrumental, apologetic and guilt-ridden modernity would have its own consequences. MAO College was an unabashedly political project — but not against the British. Sir Syed preached quietism vis-a-vis them.

There is a lot in Sir Syed’s corpus to enable a good apologia for him. But disingenuous arguments like India not yet being a nation when Sir Syed burst into a vituperative tirade against the fledgling Indian National Congress are forwarded by those who secretly cling to the two-nation theory. India has been a civilisational entity, with a craving for political unity, from time immemorial. A prerequisite for nationalism is love for the history and culture of a country. The ashraf religiously guarded itself against such sentiments. Democracy is inherent in nationalism. A privileged class couldn’t be its best proponent.

A thinker is lent relevance by his disciples. Sir Syed’s successors chose dogmatism over rationality, politics over education, and separatism over nationalism. The deft narrative makers that they were, their class interests were articulated as the religious concern of the Muslim masses. Today, Sir Syed, the thinker, needs to be partly rejected, partly transcended, and partly rehabilitated by foregrounding his rational and secular thoughts. There are two imperatives for that: The Muslim narrative makers secularise themselves, and the Muslim masses emancipate their minds from the bondage of ashraf.

(The writer is an IPS officer. Views are personal)

Source: Read Full Article