The first meeting between foreign ministers of India, Israel, UAE and US suggests that Delhi is now ready to move from bilateral relations conducted in separate silos towards an integrated regional policy

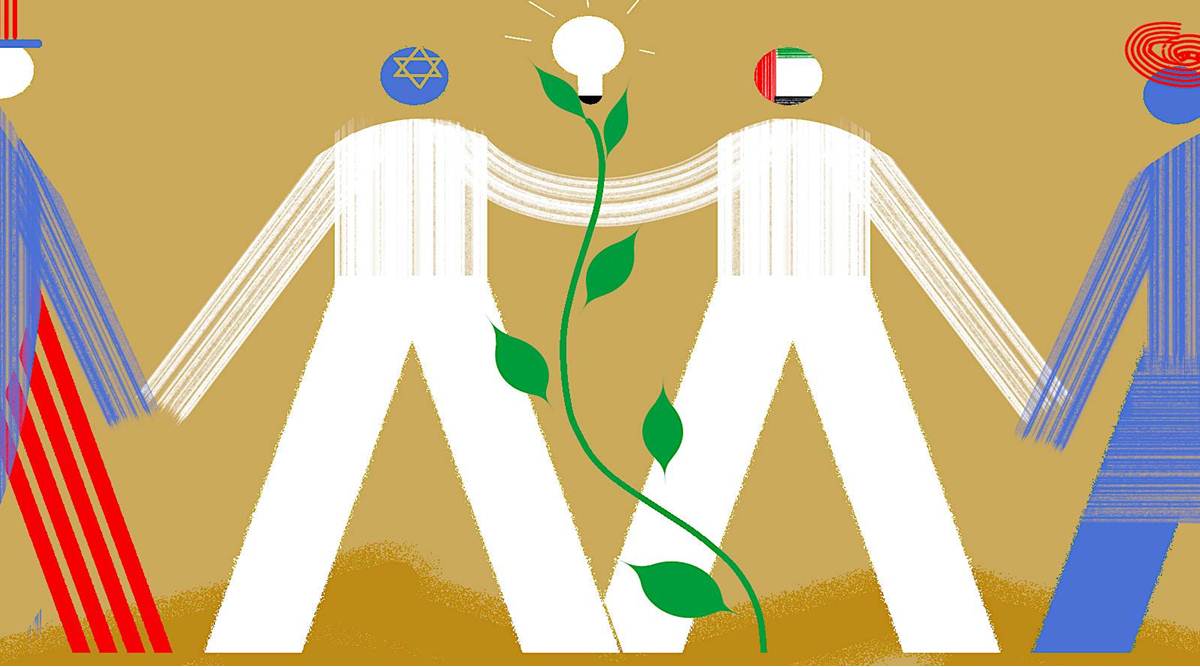

The first-ever meeting between the foreign ministers of India, Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States marks an important turning point in Delhi’s engagement with the Middle East. This four-way conversation is one element of external affairs minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar’s ongoing visit to Israel this week. India’s establishment of full diplomatic relations with Israel nearly three decades ago broke the ideological shackles that severely limited Delhi’s post-independence foreign policy in the vital but politically charged Middle East.

The new minilateral suggests India is now ready to move from bilateral relations conducted in separate silos towards an integrated regional policy. As in the Indo-Pacific, so in the Middle East, regional coalitions are bound to widen Delhi’s reach and deepen its impact.

The idea of an Indo-Abrahamic Accord between India, the UAE and Israel was first suggested by Mohammed Soliman, an Egyptian scholar based in Washington. I discussed the pursuit of Soliman’s idea in this column a couple of months ago. (‘India and greater Middle East’, IE, August 3). Our focus, then, was on India taking full advantage of the normalisation of relations between Israel and the Arabs under the so-called Abraham Accords unveiled in Washington during September 2020. The quick movement of this idea — of adding “Indo” to the Abrahamic Accords — from think tank chatter to the policy domain underlines the extraordinary churn in the geopolitics of the Middle East. It also points to new openings for India in the region and ever-widening possibilities for Delhi’s strategic cooperation with Washington.

Last year, the Abraham Accords did not receive universal approbation; for many critics in the US and beyond, they were part of Trump’s diplomatic gimmickry. A year later, we find President Joe Biden has embraced Trump’s path-breaking political initiative in the Middle East. As in the case of China and the Indo-Pacific, where Biden has made Trump’s policies his own, the White House is building on his predecessor’s legacy in the Middle East. There is one important difference though. Unlike Trump, Biden continues to insist on the “two-state solution” to the dispute between Israel and Palestine.

In Israel, a new government led by Naftali Bennett replaced the 12-year reign of Benjamin Netanyahu in June. Bennett is promising to “shrink the conflict” with the Palestinians that was widened by Netanyahu. Meanwhile, economic and technological cooperation between Israel and the UAE has been growing by leaps and bounds. The moderate policies of Biden and Bennett as well as the deepening ties between Israel and the UAE are conducive to bolder Indian policies in the region.

One of the important gains of India’s recent foreign policy was in the simultaneous expansion of Delhi’s cooperation with Israel and the Arab world. In the past, the Indian foreign policy establishment was convinced this was impossible. India’s new foreign policy pragmatism broke from that assessment and demonstrated the feasibility of a non-ideological engagement with the Middle East.

This diplomatic pragmatism allows Delhi to reimagine its policies towards the Middle East. Thinking of the US as a partner in the Middle East is part of the reimagination. For long, India defined the US, and more broadly the West, as part of the problem in the Middle East. As a result, Delhi kept a reasonable political distance from the US in the region.

The steady improvement of India-US relations in the 21st century, including the recent convergence of views on the Indo-Pacific, did not make much difference to this policy. Instead, we saw the formulation of a new ideological principle in recent years — that expanding cooperation with the US to the east of India does not mean Delhi will work with Washington to the West of the Subcontinent.

The new minilateral consultation with the US, Israel and the UAE should start breaking that political taboo. Delhi knows that the US wants to downsize its expansive role in the Middle East developed since the 1970s. The US is unlikely to quit the region, but it wants to reduce some of its regional burdens and strengthen its local partnerships. Many regional powers were quick to see this change and have significantly expanded their activism. Delhi is late to the party.

It is perhaps too early to call the new minilateral with the US, UAE and Israel the “new Quad” for the Middle East. It will be a while before this grouping will find its feet and evolve. After all, it took quite some effort to build the Quad in the east with Australia, India, Japan and the United States.

What is the kind of agenda that this group can develop? Like the eastern Quad, it would make sense for the new Middle Eastern minilateral to focus on non-military issues like trade, energy, and environment and focus on promoting public goods. A ministerial meeting of the US, UAE and Israel in Washington last week to mark the first anniversary of the Abraham Accords set up two working groups to promote trilateral as well as broader regional cooperation. One working group is focused on strengthening religious tolerance and the other on water and energy issues.

The new “Quad” in the Middle East is unlikely to be India’s only new coalition in the region. It, in fact, provides a sensible template to pursue wide-ranging minilateral partnerships in the region. India’s new regionalism to the west of the Subcontinent must also be informed by shifting political geographies.

Consider, for example, the recent emergence of the Eastern Mediterranean as a geopolitical entity connecting a number of countries, including Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, and Palestine. The new region cutting across old mental maps — segmenting Europe, Africa, and the Middle East — is being shaped by several factors.

One is the discovery of natural gas all along the eastern Mediterranean. Second is the reassertion of its historic regional leadership role by Egypt. A third is the growing role of the Gulf countries — UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia — in reshaping the geopolitics of the region. A fourth factor involves Turkey’s sharpening conflicts with Greece, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE triggered by President Recep Erdogan’s overweening ambition. Finally, major powers including France, Russia and China are being drawn into the Eastern Mediterranean.

India has many old and new partners in the region and it can now work with them in multiple formats and overlapping combinations. Meanwhile, there is much to be done in realising the full potential of the “Indo-Abrahamic Accords”.

The International Federation of Indo-Israeli Chambers of Commerce says combining India’s scale with Israeli innovation and Emirati capital could produce immense benefits to all three countries. Add American strategic support and you would see a powerful dynamic unfolding in the region.

Beyond trade, there is potential for India, UAE and Israel to collaborate on many areas — from semiconductor design and fabrication to space technology. Success on the trilateral front will open the door for extending the collaboration with other common regional partners like Egypt, who will lend great strategic depth to the Indo-Abrahamic accords.

The writer is director, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore and contributing editor on international affairs for The Indian Express

Source: Read Full Article