Taken together, the European cemeteries, tell a story of the aspirations, hardships, and the cultural exchange that went into creating a pluralistic India.

Hindoo Stuart lies buried here.

But in stark contrast to the Graeco-Roman arches and pillars adorning the tombs of the other Englishmen buried in the 250-year-old South Park street cemetery, Stuart’s grave is studded with miniature temple domes and tantric figurines.

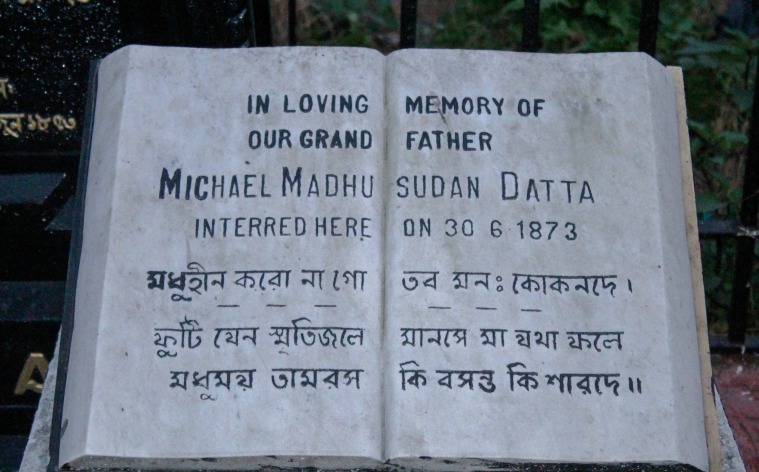

“Stuart had specified in his will that he wished his tomb to be decorated with Hindu motifs, and the British presidency ensured that his desire was met,” says Souvik Mukherjee, Assistant professor of Cultural Studies in Presidency University and an authority on colonial cemeteries in India. Stuart, an officer in the English East India Company, was so enamoured with Hindu culture that he would enthusiastically urge all Europeans to embrace it.

As Mukherjee took me around the grand relics of the colonisers who died on Indian soil, he told me about his obsession with cemeteries: “They tell you a lot about the history that is missed in other places.”

In one corner lies the large pyramid tomb of Elizabeth Jane Barwell, daughter of a colonel in East India Company, believed to be the most beautiful girl in Calcutta when she arrived. In another corner lies Rose Alymer, who was in love with the English poet Walter Savage Landor, and is believed to have died upon consuming pineapple. “In essence the colonial establishment was built brick by brick by ordinary people, like the clerks, the school masters, the merchants. Cemeteries tell us about these people,” says Mukherjee.

Yet, when the colonisers left Indian shores for good, the cemeteries carrying their dead remained neglected and decaying. While some were brought under the purview of the Archaeological Survey of India, a large majority lay uncared for and many were even destroyed.

It was only in the mid 1970s, with the establishment of the British Association for Cemeteries in South Asia (BACSA), that an attempt was made to map and preserve European cemeteries. Over the years, isolated efforts have emerged to document the cemeteries of the Dutch, Scottish, French, and Portuguese cemeteries both in India and in the home countries of the colonisers.

For instance, in 2014, Mukherjee carried out an exhaustive exercise of documenting and archiving in digital form, the lives of those buried in the Dutch cemetery in Chinsurah and the Scottish cemetery in Kolkata. Similar efforts were also made by the Art and Architecture Research Development and Education (AARDE) while conserving the Dutch cemetery in Pulicat in Tamil Nadu.

Last month, the Dutch Dodenakkers.nl foundation in collaboration with the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands opened up a digital portal, ‘Shared cemeteries’, to map their funerary heritage in former colonies like Suriname, Japan, Indonesia and India. The objective, as they say is to connect with local researchers of Dutch cemeteries and document the shared heritage. “There are about 15-20 Dutch cemeteries in India. Unlike in Indonesia where the Dutch ruled, in India they went only for trade. Consequently, the cemeteries there are different from those in other colonies, and are a product of shared cultural heritage,” says Rene Ten Dam, project manager at Shared Cemeteries.

Taken together, the European cemeteries, tell a story of the aspirations, hardships, and the cultural exchange that went into creating a pluralistic India.

The story of colonial India as told by the European cemeteries

Colonisation by European powers has shaped much of India as we know it today. But what happened when the colonisers died in India tells us a lot about the many obstacles that had to be overcome in order to build the colonial empire.

It is indeed astonishing to note that the idea of a separate space for cemeteries appeared in India much before they did in Europe where the dead were buried inside church premises till about the 18th century. “Aside from a few handful that date from the 1700s, cemeteries in Britain mainly emerged during the first half of the 19th century,” writes historian Elizabeth Buettner in her article, ‘Public memory and Raj nostalgia in postcolonial Britain and India’. She notes how the notoriously high mortality rates among Europeans due to tropical diseases in India contributed at least in part to a special piece of land being created for burying the dead. More than two million Europeans are known to have died in India as per BACSA’s estimates. So grim was the fate of those sent across to the subcontinent that if one managed to survive more than two monsoons, he or she would be deemed to be leading an accomplished life.

Consequently, the earliest British cemeteries in India dates back to the 1600s outside Surat, and even older ones built by the Portuguese can be found in Goa.

The story of Kolkata’s South Park Street Cemetery is case in point here, having been established as space for the dead fell short in the older cemetery built in 1690 in the area where the St Johns Church stands today.

“The condition was so bad that people were piling up graves over each other, and many would even leave their dead to rot in the ground,” says Kolkata heritage expert Tathagath Neogi, also founder of the heritage walks organisation ‘Immersive trails’. Neogi explains that by 1757 as European population in Calcutta had increased and those living around the cemetery at St Johns complained of the bad odour from rotting dead bodies, it was decided that a new cemetery space would now have to be opened. That is how the South and the North Park Street cemetery was opened in 1767, in an area which was then the outskirts of the city.

Equally interesting is how the English, French, Portuguese, Dutch, negotiated land and religion among themselves when it came to burying their dead. When Eduardo Tiretta, an Italian Catholic who was the Superintendent of streets and buildings in Calcutta in the late 18th century, had to bury his wife, Josephine Teritta who was a French Catholic, he first went to the Portuguese cemetery located at the Murgihata Street. As a Catholic, he would have been averse to burying his wife in the Protestant British cemetery. However, the Portuguese, themselves struggling with a space crunch, informed him that older graves are dug up every three or four years to make space for new graves. Unwilling to accept a similar fate for his wife’s grave, Tiretta brought a piece of land next to the North Park Street Cemetery which went on to be known as the French Cemetery. The cemetery, which has now been razed down, carried the burials of several hundred Jesuit preachers and French employees of landlords in Calcutta.

Religion as we see was also the reason why the Scottish decided to build their own cemetery in 1820. The Scottish being Presbyterian were unwilling to use the cemetery of the English who were Anglicans.

As pointed out by Mukherjee, “in a petition signed by the Kirk session of Elders in 1820, it was stated ‘in every place, people, countries or of different religious persuasions have always separate Burial Ground for themselves.’” The Scotts also pointed out that the burials in the English grounds were too expensive. “Apart from Scottish, dissenters of the Church of England were also buried here. Moreover, when the Church of Scotland underwent a division in 1843, its impact was felt in the Scottish cemetery in Calcutta in terms of who would be allowed to be buried there,” says Mukherjee.

However, it is not rare to come across isolated Scottish tombs in English cemeteries. The dead among the Dutch and the English could also be found in each others’ cemeteries. At the South Park Street Cemetery, for instance, we come across the grave of George William Hessing, the Dutch military officer who, like his father John William Hessing, served in the Scindia army in the 18th and 19th centuries. While junior Hessing lies buried among Englishmen in Kolkata, his father’s tomb, popularly known as the red Taj Mahal, is in the Christian cemetery in Agra.

Graves of Japanese, Italians, Armenians and others located inside the colonial cemeteries, tell the story of an India which was a bustling global trade destination. Xavier Benedict, the founder of AARDE, says that while conserving the Dutch cemetery at Pulicat, they came across one Japanese grave. “On researching further we came to realise that Pulicat happened to the only port where the Japanese exchanged gold for cotton,” he says.

Finding the Indian in European cemeteries

An interesting aspect of colonial cemetery is the extent to which they collaborated and shared space with Indians. “One can say that needing a cemetery is one of the foundational elements of establishing community. At the same time, this new space transforms or creolises the practices that the Europeans brought with them,” explains Ananya Jahanara Kabir, professor of English Literature at Kings College, London, and the co-founder of the online portal ‘Le Thinnai Kreyol’. “Local stone and local craftsmen are needed to create the headstones (for example). At the same time Christian rituals and prayers are indigenised.”

Speaking about their documentation of the Dutch cemeteries in India, Ten Dam says “the Dutch were very influenced by Mughal culture and used a lot of local workers. Most of the floral patterns and symbolism we see in the Dutch tombs are in fact Indian.” He says such development of Dutch cemeteries in India was in stark contrast to their presence in Japan. “In Japan, the Dutch were the only western country allowed to bury their dead. But they were not allowed to show any religious symbolism. So unlike the elaborate graves in India, the Dutch cemeteries in Japan are very sober and simple,” he says. Similarly, in Suriname, where the Dutch ruled from 1667 to 1954, there were hardly any local resources available to build cemeteries. Consequently, and unlike the graves in India, a lot of stones and other masonry products had to be brought in from Europe to build their cemeteries.

But were the Indian dead allowed to be buried alongside the graves of the colonisers? Experts say that it differs case by case. In Goa, for instance, where the oldest Roman Catholic cemeteries were built during the Portuguese colonial rule that started in the 16th century, graves of local converts are found in large numbers seated along with those of the Europeans. “You cannot call the graveyards in Goa Portuguese or European cemeteries. Even though the first organised burial grounds of Europeans were definitely built in Goa, these are Roman Catholic cemeteries attached to a church and those buried there also belonged to the community of native converts that arose in the colonial period,” explains Vivek Menezes, a well known writer based in Goa. However, in the churches of old Goa, he says one comes across graves exclusively of European noblemen like the Portuguese, Italians and Germans.

The only exclusively European cemetery found in Goa is the British cemetery in Dona Paula, which consists of the graves of those British who died while their country occupied Goa during the Napoleanic wars of the early 19th century. “The British variant of Christianity was different, which is why they would not want to use a Catholic graveyard,” says Menezes. “But they were also extremely racist, which is why in most British cemeteries in other parts of India you will see that the local graves are segregated from the European ones.”

Mukherjee, however, says it is not exactly clear whether the British did exhibit racism in death since in the English cemetery at Lower Circular Road and the Scottish cemetery in Kolkata, we do come across Indian graves. “While I have not come across an Indian grave in the Dutch cemetery in Chinsurah, I am not sure if no Indian was buried there since some of the graves are unmarked,” he says. Mukherjee explains that Indian graves are present on a different side of the Chinsurah Dutch cemetery. “It’s difficult for me to assume that the Dutch segregated the two sets of graves since we do come across a few Dutch tombs among the Indian burials.”

Pondicherry-based authur Ari Gautier describes the interesting way in which the French and English cemeteries have incorporated Indians there. “At Uppalam, there are two cemeteries on either side of the road that goes to Cuddalore. The French cemetery on the left carries a mix of graves belonging to the whites, the locals, the creoles (mixed race) as well as those of Protestants and Jews. The one on the left was originally an English cemetery, but later even Indians came to be buried there. Interestingly, the Indians buried there are only those who belonged to an elite class.,” says Gautier who is also the co-founder of ‘Le Thinnai Kreyol’

Left to decay

H E Busteed in his book, ‘Echoes from Old Calcutta’ published in 1908 lamented the decaying conditions of English cemeteries and explained it so: “In a country where the European from his very arrival, looks and pines for the day when he may be favoured enough and fortunate enough to be able to leave it again, the memorials of the dead of a previous generation have but little chance of being looked after by those succeeding.”

The impermanent nature of European settlements in India meant that burials of the dead were hardly cared for. This situation continued to be so long after Independence. Cultural anthropologist Ashish Chadha, in his research paper ‘Ambivalent heritage: Between affect and ideology in a colonial cemetery’, notes: “Soon after Indian Independence in August 1947, the erstwhile colonial government decided to withdraw funding for the upkeep of colonial civil cemeteries throughout the country.” The military graves were put under the aegis of the Imperial War Graves Commission.

Chadha writes that in 1948 it was decided that the North and South Park street cemeteries would be leveled and a ‘Garden of Remembrance’ constructed in its place. “Local British and Anglo-Indian citizens in Calcutta met this with stiff resistance and voices of protest were also raised in London,” writes Chadha. Questions were raised in the British Parliament regarding why one should forget “the unsung army of middle class and especially those women of whom so many have devoted their lives to the ‘women and children of India’ and whose service and devotion is recounted for all time on their tombstone.”

Consequently, some amount of funds collection resulted in the South Park Street Cemetery being retained, while In 1953 the North Park Street cemetery was torn down. It contained the graves of Richmond Thackery, father of novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, and that of yet another ‘white Mughal’, James Archilles Kirkpatrick. While the plaques from the cemetery have been moved to the South Parth Street one, in its place has come the Assembly of God Church school and the Mercy Hospital. “Pressure by the office of the then Chief Minister of West Bengal, Dr B C Ray, was decisive in this demolition,” writes Chadha. “He was rather worried about these cemeteries as they were being used as public latrines as well as by goondas (ruffians) and other bad hats in Calcutta for clandestine purposes.”

A similar fate was in store for the French cemetery which was cleared in 1977 to make way for the Apeejay School.

Benedict says one of the main reasons why cemeteries have disappeared in recent years is that stones from the tombs are frequently taken out to be used as construction material. “The Dutch cemeteries in Tuticorin, Kayalpatnam, and parts of Nagapattinam have vanished completely,” he says.

Further reading

Public memory and Raj nostalgia in postcolonial Britain and India by Elizabeth Buettner

Echoes from Old Calcutta by H E Busteed

Ambivalent heritage: Between affect and ideology in a colonial cemetery by Ashish Chadha

British cemeteries in South Asia: An aspect of social history by Theon Wilkinson

Les tisserands de Thieux by Ari Gautier

Source: Read Full Article