How artists are exploring our essential relationship with food to defy prejudice, mark history and nurture connections

At the 2017 Art Basel, the usually well-turned-out Subodh Gupta was seen walking up and down the aisles wearing an apron. Instead of mixing paints or setting up his sculptures, he was grinding spices, chopping vegetables and stirring a wok in a makeshift kitchen he had designed as part of an installation made of second-hand utensils. Alluding to India’s economic and social transformations, the enormous structure also housed a dining table. Here, Gupta served his seven-course feast of authentic Indian cuisine, including dishes from Bihar, to over 20 guests in four daily sittings, for a week. The spread included lentil soup, bhel puri, khichdi and saffron yogurt layered with slices of banana. The guests ate, chatted and made new friends.

“Food might have become politicised and factors such as religion and ethnicity might have come to influence it, but it certainly has the ability to bring people together. That is what I want to do. People sitting on the same table don’t just eat, they have conversations. The performances encourage inclusivity in times of growing intolerance. People are not mere spectators, they are part of the act,” says Gupta, 57.

The project “Cooking the World” at Art Basel was not his first meal-based installation/performance. Known for his passion for cooking, the Gurugram-based artist has rustled up meals at prestigious venues the world over, from the 2013 Performa in New York to his 2018 solo at Monnaie de Paris. “If I hadn’t become an artist, I would have been a chef,” he says.

Among the numerous ways that COVID-19 has altered our lives, the virus has also changed our relationship with food. While we watched migrants walking back to their villages for want of adequate food, on the other end, visuals of sourdough bread and pasta in our homes filled social media. If some turned to healthier eating, others perfected recipes. At a time when regional cuisines have become hyper-global, the world connected as much through food as through its visuals. While Gupta gathered hearty comments for his recipes of one-pot mutton curry and Vietnamese pancake posted on social media, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, introduced the series “Cooking with Artists” in April 2020. It has New York-based artist Anicka Yi preparing lemon pasta with parmesan, peas and fresh herbs, and architect-artist Hugh Hayden baking the perfect cornbread pudding.

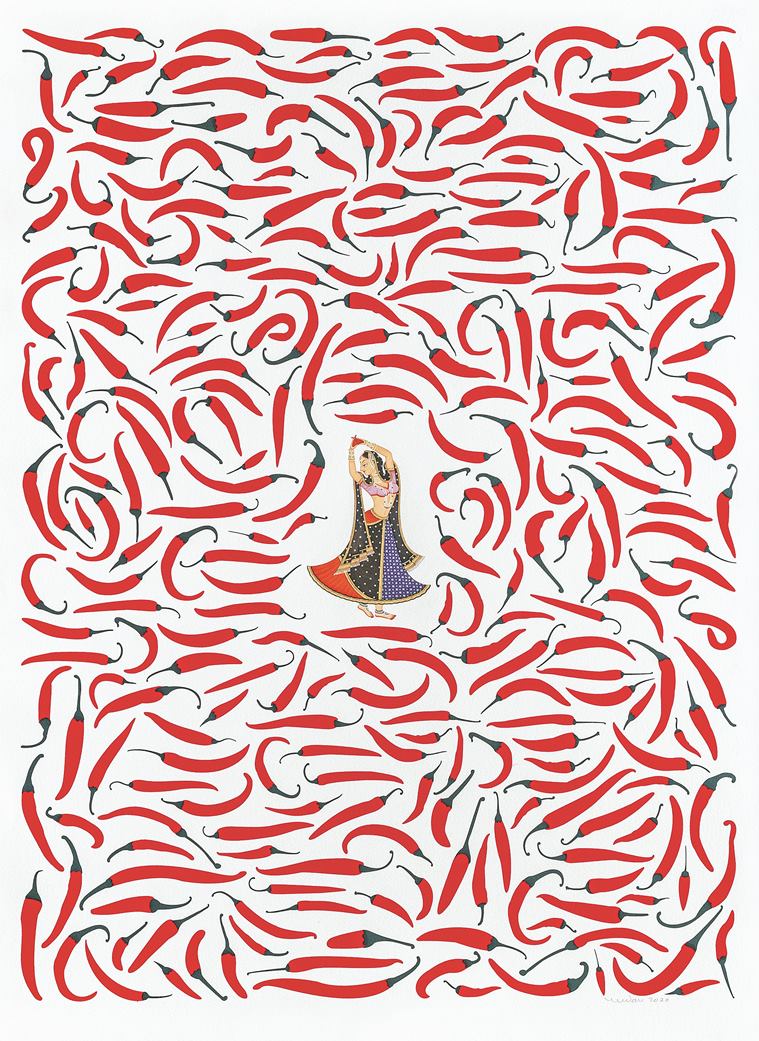

“As we remain homebound and isolated, food is a great source of comfort. It binds us to one another and our ancestors, allowing us to draw upon a wealth of family recipes and stories associated with it. Through the past year, people have time and again turned towards the simple joy of cooking or eating,” says Kamini Sawhney, director of Bengaluru-based Museum of Art & Photography. An ongoing online exhibition by the museum showcases the association between food and art through over 15 pieces from its collection. Each exhibit has an accompanying text on the primary ingredient and a recipe from a team member, bringing together nostalgia, culinary practices and their love for art. One such is an 18th-century cotton robe from the Coromandel Coast with pomegranate motifs, which we are told is one of the oldest fruits in the world that entered India from Iran. If a 1980 untitled KG Subramanyan canvas has a woman inspecting a fish basket, Jogen Chowdhury’s 1977 ink and pastel Fruit-I has the capsicum as its protagonist.

The intersections of food and art are centuries old, even as the latter has served as a register of the times. The Romans not just hosted grand banquets but also painted them; while the walls of the Egyptian pyramids have drawings of food for the afterlife of the deceased; The Bhimbetka cave paintings in Madhya Pradesh have hunting scenes and picking of wild plants for food. In medieval times, as trade grew and new lands were conquered, images of food symbolised prosperity in Western art. For instance, Italian Renaissance artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo painted portraits by piecing together exotic fruits, vegetables and flowers, and 17th-century still life Flemish artist Joris van Son depicted decorative fruit baskets.

The tradition of food as an object in still life continued into modern times. Dutch post-impressionist Vincent van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters (1885), of farmers consuming a modest meal of potatoes and coffee, is a stark contrast to the much-brighter Still Life with Blue Enamel Coffeepot, Earthenware and Fruit (1888), inspired by his time in Paris. Spanish artist Salvador Dali, on the other hand, brought surrealism into his studio and kitchen, as is evident in his 1973-cookbook Les Diners de Gala. For an artist who famously stated “My work is my diary”, Cubist master Pablo Picasso’s Spanish-French palate often reflected in his palette too — from a basket of fruits in Fruit Bowl with Fruit (1918) to a delectable lobster set on a platter in Le Homard (1945).

In India, Raja Ravi Varma, the father of modern Indian art, turned to European realism for his depictions dominated by Indian mythological deities and royalty. He, too, painted a fruit basket in oil, The Maharashtrian Lady. The more sensual Woman Holding a Fruit has a young woman with a lemon in one hand.

It’s not just the presence but also the absence of food that caught the attention of Indian artists. One of FN Souza’s most recognised early paintings is Indian Family (1947), with a family seated with empty bowls, while the table inside offers a lavish spread of fruits, fish and wine. The Bengal famine of the 1940s has been documented for posterity in the artwork of Somnath Hore and Chittaprosad Bhattacharya. The latter produced disturbing sketches of the undernourished in his book Hungry Bengal, copies of which were destroyed by the British. In one of the captions, Bhattacharya writes: “The dacoits carried away the half-boiled rice, the last two pieces of brassware that the unfortunate victims still had, and even the dirty rags they had on them. The woman had nothing to cover herself with for two days.”

Despite being a marker of inequality, food, with all its associations, can also champion cultural exchange. “Food can be a method to create a community through pleasure and thereby form a fulcrum to start conversations,” says artist Anita Dube, 62. In her 1996 sculpture performance Oh Tieresias at Eicher Gallery in Delhi, she barbecued 101 ceramic eyes on a skewer and served it to guests as mementos. “It symbolised the violent gaze,” says Dube. As the curator of the 2018-19 Kochi Muziris Biennale, she included multiple projects around food. Chefs Anumitra Ghosh Dastidar (Goa) and Prima Kurien (New Delhi) explored indigenous rice strains of India under the banner of Edible Archives, while Kochi-based artist Vipin Dhanurdharan had his community kitchen at Aspinwall House, where visitors were encouraged to prepare, serve and share meals. Dhanurdharan’s inspiration was a community feast, organised by social reformer Sahodaran Ayyappan, at Cherai, Kerala, in 1917, to counter untouchability. “The kitchen was a space where everyone was equal, a miniature model of a utopian world that I imagine and is much needed now,” says Dhanurdharan, 32.

Delving deeper into the imposition of cultural hierarchies and divisiveness through food traditions, meanwhile, is the art practice of half-Dalit, half-English artist Rajyashri Goody. Since 2017, she has been collecting extracts from Dalit literature that relate to food and has been compiling “recipes” into booklets. It has writers describing hunger, the process of sourcing ingredients and even the experience of eating. Manusmriti, the Hindu law book, which condemns inter-caste interactions, is an active ingredient, in the form of paper pulp, in works such as Joothan (2018) and Lal Bhaaji (2019).

Meanwhile, the series “Caste and Food” on the Instagram handle The Big Fat Bao underlines caste-based culinary dynamics. The illustrations complement the text, showing how several traditional Dalit recipes are telling of discrimination — from the use of meat, goat, cow, buffalo and sheep blood solidified to prepare rakti, the main ingredient of the dish Lakuti, to the consumption of millet as a cheaper alternative to wheat. “Caste, gender, and environment constantly intersect at the site of food. There is an intricate relationship between food and caste economy in addition to the construct of division of labour,” says the introduction to the series.

The personal becomes political. In artist Pushpamala N’s work, she pays tribute to her friend and neighbour, journalist-activist Gauri Lankesh, who was killed in 2017. Her performance, titled Gauri Lankesh’s Urgent Saaru, involved preparing rasam from a recipe shared by Lankesh. Dressed as Mother India — ostensibly addressing accusations of Lankesh being described as “anti-National” — the Bengaluru-based artist served rasam to the audience, in memoriam.

More recently, several artworks have pointed to the pronounced irony of debt-ridden farmers dying of hunger. “If no one does farming, what will everyone eat,” questions Paradsinga-based artist Shweta Bhattad, 37. She works with the very source of food: seeds. Packed in seed balls, a variety is shipped on order in packaging designed by Bhattad with her team, under the label Gram Art Project.

Artist duo Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra’s travelling exhibition “Farmer is a Wrestler” (2019) was centred on the ongoing agrarian crisis. For its opening, the duo opted for a simple menu with items made from bajra. “It seemed most appropriate not to have a typical opening that is celebratory. We worked with groups that are researching lost recipes of the regions,” says Tagra. The duo has incorporated food in their practice to address multiple issues, including building connections between the history of grains and evolution of society in “Bread, Circuses & You” (2019).

They are currently working on two games, one that discusses the overwhelming odds of women in Indian agriculture and another dedicated to climate change and food. “We need to question what we are eating and how climate change affects every strata of society. How urgent is it to act? Where will the next meal come from?” says Tagra.

Source: Read Full Article