From the perspective of job creation, India is facing a double whammy as employment falls in both manufacturing and services sectors

Dear Readers,

The words “lives” and “livelihoods” are often mentioned together. But the ongoing Covid pandemic has driven a wedge between these two: Measures aimed at saving lives are proving to be terrible for livelihoods. Over the past couple of weeks, we have seen several studies and surveys that pointed to the unfolding crisis in livelihoods.

An important one was the State of Working India (SWI) 2021, which was brought out by the researchers at Azim Premji University. The report, which is an annual feature, documented the impact of one year of Covid-19 in India, on jobs, incomes, inequality, and poverty.

The SWI 2021 went beyond confirming the grim reality unfolding across the country by providing a tangible set of data points for analysis and policy action. The SWI 2021 showed that the pandemic had forced people out of their formal jobs into casual work, and led to a severe decline in incomes. Not surprisingly, there is a sudden increase in poverty over the past year.

“Women and younger workers have been disproportionately affected. Households have coped by reducing food intake, borrowing, and selling assets. Government relief has helped avoid the most severe forms of distress, but the reach of support measures is incomplete, leaving out some of the most vulnerable workers and households,” it stated.

It is important to note that the SWI 2021 provides the impact on livelihoods before the second Covid wave unfolded and, in that sense, it is quite likely that more bad news will follow unless the government urgently undertakes steps to compensate people for the loss of earnings.

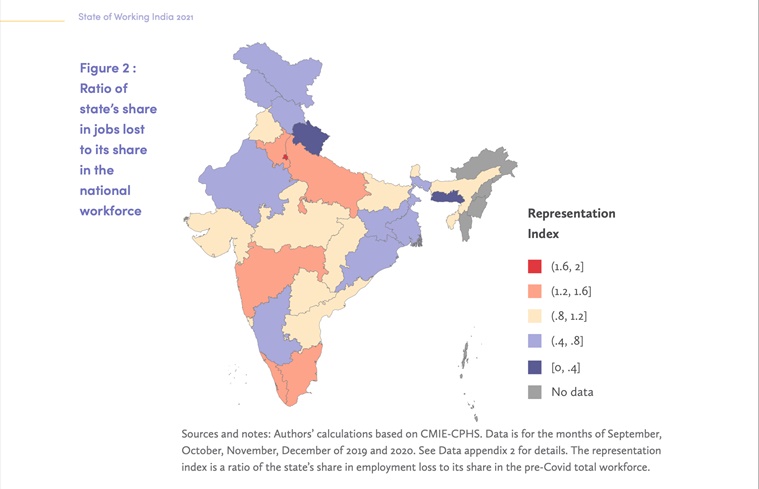

Among some of the interesting findings was this map, which provides a state-level job loss index. This index is essentially the ratio of a state’s share in jobs lost to its share in India’s workforce. Maharashtra, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and Delhi, contributed disproportionately to job losses. Unsurprisingly, these are also the states that suffered the maximum Covid caseload.

But Covid is likely a once-in-a-century phenomenon and as such, policymakers can brush aside its adverse effects as a one-off.

What is more worrisome than the SWI data, however, was a report brought out jointly by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) and Centre for Economic Data and Analysis or CEDA at Ashoka University. It pointed to an ailment of the Indian economy that has not only been a longstanding one but also one that has gotten worse over the past few years even without the help of Covid.

The CMIE-CEDA report looked at the employment in India and its distribution across different sectors such as agriculture, industry and services.

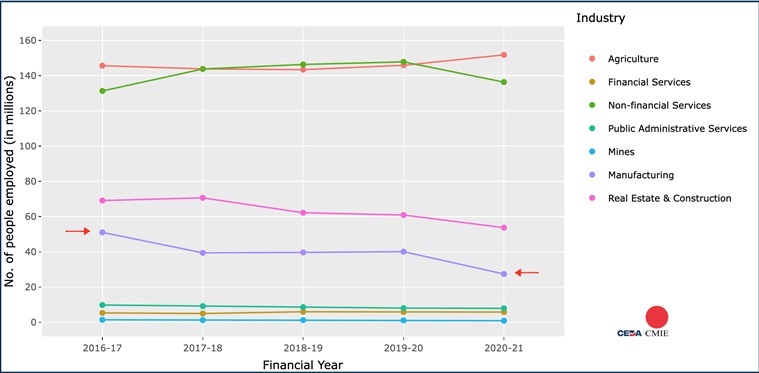

The chart alongside is based on CMIE’s monthly time-series of employment by industry going back to the year 2016. It shows employment data across seven sectors, viz. agriculture, mines, manufacturing, real estate and construction, financial services, non-financial services, and public administrative services. Between them, these sectors account for 99% of total employment in India.

What stands out the most is the trend in manufacturing — highlighted by the red arrows. The number of people employed in the manufacturing sector of the economy has come down from 51 million to 27 million — that is, almost halving in the space of just four years!

There are other worrying trends as well.

For instance, the number of people employed in agriculture is going up (look at the top-most line in pink). Equally disheartening is that employment in non-financial services (such as providing education and entertainment industry etc.) has fallen sharply (look at the second line from the top in green colour).

Why are these trends worrisome?

It is important to understand that traditionally Indian policymakers have been of the view that the manufacturing sector is our best hope to soak up the surplus labour otherwise employed in agriculture. Manufacturing is well suited because it can make use of the millions of poorly educated Indian youth, unlike the services sector, which often requires better education and skill levels.

For the longest time, India has struggled to get its manufacturing industries to create a growing bank of jobs. But, and this is what the CMIE data shows, what is happening in the past 4-5 years is that far from soaking up excess labour from other sectors of the economy, manufacturing is actually letting go of workers.

Providing the details, Mahesh Vyas (the CEO of CMIE) says that most of the manufacturing jobs lost are in labour-intensive sectors such as textiles, construction material (like tiles etc.) and the food processing industry. For instance, jobs in textiles manufacturing have come down from 12.6 million in 2016-17 to just 5.5 million in 2020-21. Over the same period, employment in construction material firms has shrunk from 11.4 million to just 4.8 million.

The dip in non-financial services is also worrisome but it is likely to be a Covid-specific trend. Over the past year, contact services such as a dine-in restaurant have been largely ruled out. With the second wave underway, and the possibility of a third one later, it is quite likely that contact services may continue to lose workers.

That is why, explains Vyas, India has seen a hike in the number of people “employed” in agriculture over the past year. “This is nothing but disguised unemployment,” he says. Essentially, labourers and workers are returning to their rural homes in the absence of jobs either in manufacturing or services.

Why is Indian manufacturing failing to create jobs?

On the face of it, every past government has come out with a policy to boost manufacturing jobs. Then why is the situation getting worse with each passing decade?

There are different ways to look at this question.

One is to look at why manufacturing has struggled to create as many jobs in the past and the second is to look at the specific reasons why manufacturing has been bleeding jobs, instead of creating them, since 2016-17.

Let’s tackle the historical question first.

Pronab Sen, the former chief statistician of India, breaks it down to the supply and demand of manufacturing firms (and products).

He says that if one looks at any of the sectors in the economy — agriculture, industry, services — starting a manufacturing unit requires the highest amount of fixed investment upfront (relative to the output that may be generated later). In other words, it is a big commitment on the part of an entrepreneur to put up a huge amount of money without necessarily knowing how it will all pan out.

What has traditionally made this truly risky, according to Sen, is the highly extractive nature of Indian governments. In simpler terms, far too often governments have been corrupt, with officials and politicians extracting bribes. The combination of these factors makes starting a manufacturing firm that much riskier and that explains the slow growth or, in other words, the weak supply of manufacturing firms.

As regards the demand for manufacturing goods, Sen points out that Indians have always consumed relatively less of manufacturing goods and relatively more of food and services.

There are two possible reasons for this. One, most Indians are quite poor and hence most of the income is spent on food. Two, repairs and maintenance are a very high part of our consumption choice. In other words, when Indians buy a manufactured product — say a refrigerator — they tend to use it for much longer than in developed countries. Moreover, even when you discard the fridge after 20 years, there is a large second-hand market for it among the lower-income groups.

Radhicka Kapoor, a Senior Research Fellow at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), looks at the same question from a policy perspective.

“The fact is that manufacturing hasn’t been able to increase its share in overall employment even since the economic reforms of 1991,” she states as she points to the share of manufacturing staying stagnant at 11% of the overall employment.

In her view, the trouble lies with Indian policymakers repeatedly neglecting the labour-intensive industries. Since the second five year plan, the P C Mahalanobis strategy was to gain self-reliance (atmanirbharta) by investing in capital intensive industries so that India does not have to import machines etc. from other countries. The hope was that the demand from Indian consumers will make the domestic industry viable. But Indian domestic demand was quite anaemic, thanks to poverty levels.

As against the capital intensive industries, which were involved in making heavy machines, the labour-intensive ones (such as leather, handicrafts, textiles etc.) were reserved for the small-scale industry framework.

But while the labour-intensive manufacturing firms could not match the capital-intensive firms in terms of GDP value or growth of output, they did have a distinct advantage of creating more jobs. But, by treating them as small-scale industries, policies held back their growth.

Moreover, she argues, India did not push for integrating its labour-intensive manufacturing in the global supply chains by aggressively following exports. Instead, the idea was to substitute imports in the name of self-reliance. Kapoor says notwithstanding the policy tweaks over the decades, this bias against labour-intensive industries has stayed.

What has happened since 2016-17?

But as the CMIE data shows, things have become worse over the past five odd years despite the Indian government unveiling its ambitious Make in India (MII) initiative and the latest Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme.

For one, as Kapoor says, India is repeating the same mistakes with MII and PLI schemes. They are again aimed more at capital intensive manufacturing, not labour intensive ones. Moreover, India is reverting to the protectionist approach, aimed at self-reliance, yet again in recent years.

She says that, unlike India, other Asian economies have exploited their comparative advantage. For instance, between 2000 and 2018, Bangladesh and Vietnam have increased in their share of global clothing exports from 2.6% to 6.4% and from 0.9% to 6.2%, respectively, while India’s share has largely remained stagnant at 3% to 3.5%.

Further, much like in the past, this time, too, the domestic demand is weak, points out Kapoor as she argues for aggressively boosting labour-intensive industries aimed at capturing the export markets.

Ravi Srivastava, Director of the Centre for Employment Studies in Institute for Human Development, Delhi, agrees that India has historically failed to transform its labour-intensive manufacturing ecosystem. But he also points to some of the policy measures taken in the past few years that have destroyed the base of Indian manufacturing.

“Look, 70% of India’s manufacturing jobs are in the informal sector and this is your base,” he says.

Both the demonetisation announced in 2016 as well as the introduction of GST in 2017 dented the manufacturing firms in the informal sector and steadfastly redistributed the demand in favour of organised manufacturing. “The two Covid waves have further hit the same informal manufacturing sector,” says Srivastava.

In other words, the growing rift in the fortunes of informal and formal manufacturing could be the reason why India is seeing such a massive decline in manufacturing jobs.

The current government has tried its level best to push for greater formalisation but it has often been accused of not understanding the nature and functioning of India’s informal economy.

Sen provides the last nugget of wisdom for policymakers.

“Clearly, for the same level of employment, formality is good. But if there is a trade-off between formality and employment generation, choosing formality may not be so beneficial. And this trade-off appears to be quite sharp in India.”

The upshot: From the perspective of creating jobs, India is facing a double whammy. The manufacturing and construction sectors are bleeding jobs instead of creating them. Making matters worse is the decline in employment in large sections of the service industry, thanks to the Covid-induced disruption.

As such, Indian manufacturing, which is still India’s best hope for creating new jobs and soaking up excess unskilled labour from agriculture, requires policymakers to target labour-intensive firms, especially in the informal sector (read MSMEs) and help them — through better infrastructure and easier regulatory support — to create millions of new jobs.

Share your views and queries at [email protected]

Mask up and stay safe,

Udit

Source: Read Full Article