Why deciding the width for mountain highways does not warrant a defence-vs-environment debate, and how destabilisation of the hills undermines concerns and the very idea of a reliable all-weather road

The Supreme Court on Thursday reserved its judgment on an appeal by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) for relaxing its September 2021 order that specified the road width under the Char Dham Mahamarg Vikas Pariyojana (Char Dham Highway Development Project) of the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH). “There is no such defence versus environment argument at all… You have to balance both concerns,” the court observed.

A flagship initiative of the Centre, the Rs 12,000-crore highway expansion project was envisaged in 2016 to widen 889 km of hill roads to provide all-weather connectivity in the Char Dham circuit, covering Uttarakhand’s four major shrines — Badrinath, Kedarnath, Gangotri and Yamunotri — in the upper Himalayas.

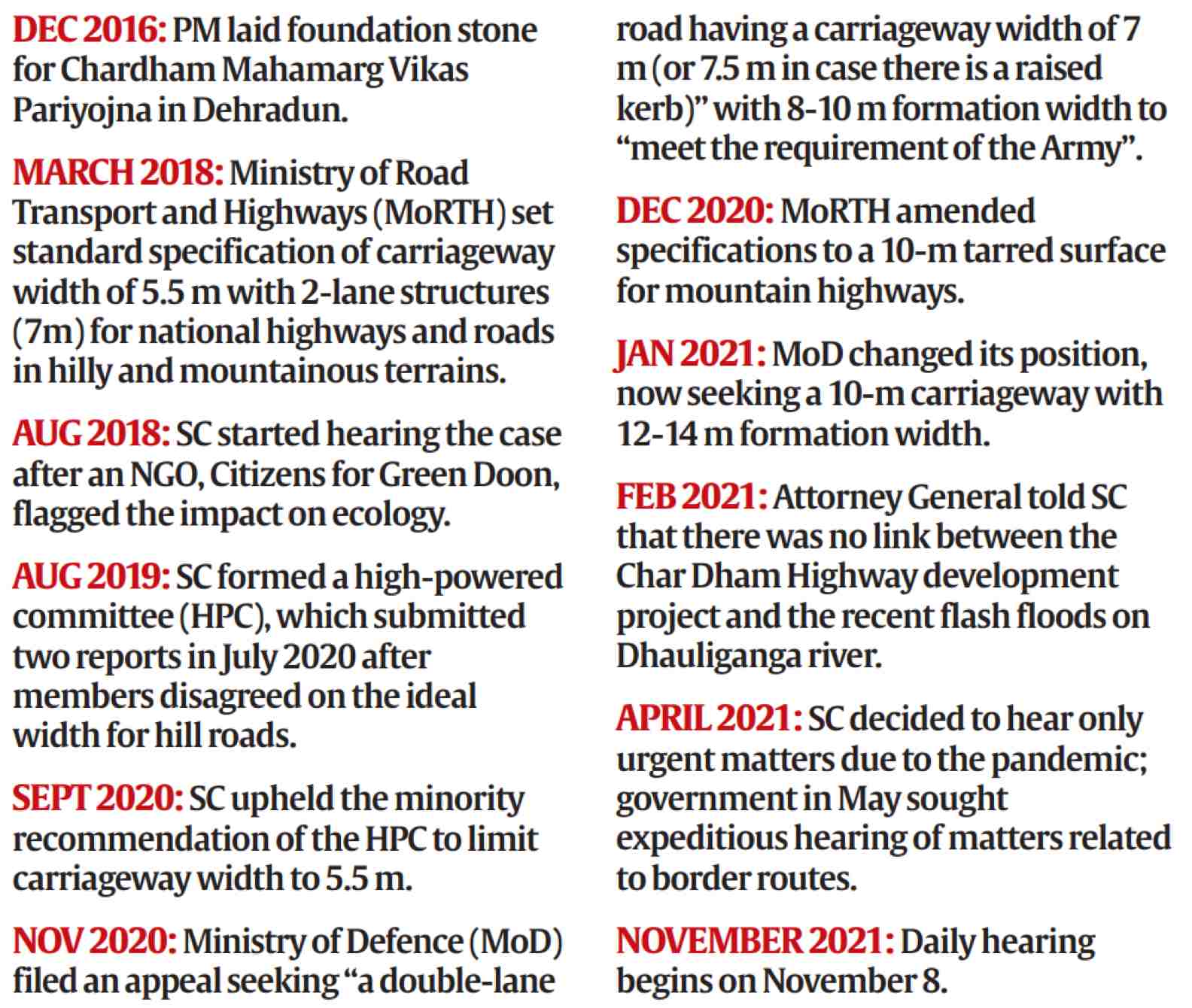

Laying the foundation stone in December 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi described the project as a tribute to those who lost their lives during flash floods in the state.

The controversy

In 2018, the road-expansion project was challenged by an NGO for its potential impact on the Himalayan ecology due to felling trees, cutting hills and dumping muck (excavated material). The Supreme Court formed a high-powered committee (HPC) under environmentalist Ravi Chopra to examine the issues.

In July 2020, the HPC submitted two reports after members disagreed on the ideal width for hill roads. In September, the Supreme Court upheld the recommendation of four HPC members, including Chopra, to limit the carriageway width to 5.5 m (along with 1.5 m raised footpath), based on a March 2018 guideline issued by MoRTH for mountain highways.

The majority report by 21 HPC members, 14 of them government officials, favoured a width of 12m as envisaged in the project following national highway double-lane with paved shoulder standards: 7 m carriageway, 1.5 m paved shoulders on both sides, and 1 m earthen shoulders on either side for drains and utilities (hillside) and crash barrier (valley side).

A wider road requires additional slope cutting, blasting, tunnelling, dumping and deforestation – all of which will further destabilise the Himalayan terrain, and increase vulnerability to landslides and flash floods.

‘No rule of law’

HPC chairman Chopra wrote to the Environment Ministry in August 2020, underlining how the project was being implemented in brazen violation of statutory norms “as if the Rule of Law does not exist”. These include:

WORK WITHOUT VALID PERMISSION: Project work and felling of trees on different stretches, adding up to over 250 km, has been continuing illegally since 2017-18. A work order issued by the state Forest Department in September 2018 was not only post facto but also legally untenable. In fact, the department had written to the developer back in February 2018: “Char Dham project is related to the ambitious plan of the Honourable PM… considering the importance of the project… tree felling in the stretches quoted above is almost complete even though doing so without complying with the conditions of the in-principle approval is a clear violation.”

MISUSING OLD CLEARANCES: Work started on stretches adding up to over 200 km on the basis of old forest clearances issued to the Border Roads Organisation during 2002-2012. This is illegal and defeats the regulatory purpose since the scope of work has changed drastically with “enormous hill cutting” undertaken. Muck has just been pushed down the slope along NH-125, posing a serious threat to the environment and local habitat.

FALSE DECLARATION: Tree felling, hill cutting and muck dumping on stretches adding up to over 200 km commenced by falsely declaring that these stretches did not fall in the Eco Sensitive Zones of Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, Rajaji National Park, Valley of Flowers National Park etc.

WORK WITHOUT SEEKING CLEARANCE: Work began on various stretches, adding up to at least 60 km, after withdrawing applications for forest clearance without furnishing reasons.

VIOLATION OF SC DIRECTIVE: Work started on stretches adding up to at least 50 km, even though the state government said in an affidavit in April 2019 that stretches where work had not already begun would be subject to the direction of the SC.

The defence angle

Even as the project grappled to come clean, it garnered support from the MoD that moved an appeal before the Supreme Court in November, seeking “a double-lane road having a carriageway width of 7 m (or 7.5 m in case there is a raised kerb)” with 8-10 m formation width to “meet the requirement of the Army”.

While conceived primarily to facilitate the Char Dham yatras (pilgrimage) and to boost tourism, the project always had a strategic angle to it as the highways would facilitate troop movement to areas closer to the China border. Suddenly, this became the sole justification for building wider roads.

But the MoD went a step further. Its affidavit on January 15 said that “unfortunately, notwithstanding the security of the country and the need of the defence forces to resist external aggression, if any, at the Indo-China Border”, the HPC chairman and two members had recommended that “no credence should be given to the needs of the armed forces”.

Chopra reacted immediately. Emphasising that “no convincing argument exists in the recent affidavit of the MoD to ignore and override the profound and irreversible ecological damage to the Himalayas that will impact each and every one of us and generations to come”, he urged the Supreme Court to ask the MoD to “withdraw imputations” of “insincerity of motive” against him and two other HPC members.

Speed versus stability

The wider the road, the quicker the defence deployment and supplies. But widening a mountain highway, particularly on the young, still-unsettled Himalayas, runs the risk of leaving the slopes more unstable.

During the hearing on Wednesday, the counsel for the NGO pointed out how three valleys in Pithoragarh situated close to the China border were cut off due to landslides for two months, pleading that the Army, as well as civilians, required a safe, reliable road and not one that remained blocked or got washed away periodically.

The way things stand

Both parties concluded their arguments on Thursday. While the NGO underlined the government’s disregard for the September 2020 court order when MoRTH unilaterally relaxed its guideline for hill roads last December, the government furnished a two-page report on the steps taken for landslide mitigation.

The judgment is likely to serve as a benchmark for “balancing both concerns” within the legal framework, and draw a not-so-fine line between vanity projects and strategic imperative.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

Source: Read Full Article