‘There are already multiple lawsuits against the IT rules.’

‘So questions of compliance are like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.’

Ritwik Sharma reports.

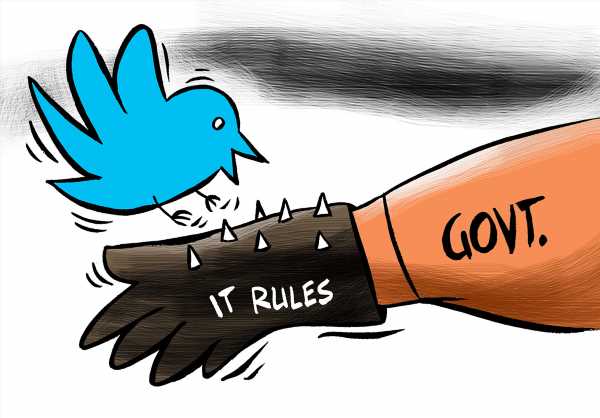

The government has said Twitter failed to comply with the new IT Rules that came into force in May.

What does it entail for the microblogging platform that has run afoul of a set of guidelines that are mired in controversy?

Also, given a stand-off between the government and the company and recent questioning of Twitter officials by the police, does it run the risk of a ban?

Here are the answers.

How does non-compliance with the IT Rules affect Twitter?

The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, in February mandated compliances for a category called ‘significant social media intermediary’ (social media firms with over 5 million registered users) that included appointments of a chief compliance officer, a nodal officer and a grievance officer.

The government has said that most major social media intermediaries shared the details within the three-month window they were given, except for Twitter.

Twitter said it had appointed a nodal contact person and a resident grievance officer, and added that it has also appointed an interim chief compliance officer (who quit this eek).

Experts, however, have said that the non-compliance may lead to the loss of protection under the safe harbour provisions accorded by Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000.

N S Nappinai, advocate, Supreme Court, and founder, Cyber Saathi, says there are three options before a company — comply, go to court and contest, or face consequences.

What it means, according to her, is that normally, that is if Twitter had complied with the rules, it would only have to worry about taking down content based on a complaint.

“Now, for the period of non-compliance Twitter can be held liable for the illegal or violative content on its platform. The extent of liability will depend on the facts of each case. And punishments could be on par with those posting the content,” she adds.

What is the recourse for the company?

Upon compliance, Twitter will get back its protection automatically, says Nappinai.

Even if the company loses its immunity, implication will still depend from post to post.

“Each post will have to be evaluated on what is the criminality or liability in it, and what can Twitter’s role amount to in that liability,” she says, adding that if an entity is not amenable to a rule, the only recourse is to go to court and get an order to that effect.

Raman Jit Singh Chima, senior international counsel and Asia Pacific director at Access Now, however, says that the government’s assertion does not have an automatic legal basis.

“Section 79 (of the IT Act) provides safe harbour. It is provided for by Parliament. But Section 79 does not say that the government can choose which intermediary is in compliance with the rules.”

Access Now has questioned the new IT guidelines and said that the government, with expanded powers under these rules, seeks to ‘restrict online content’ and ‘free expression and access to information’.

Whether Twitter is in violation is for the judges to decide, he says.

“There are already multiple lawsuits against the IT rules. So questions of compliance are like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.”

Could the government impose a ban?

A ban is not at all likely, say experts, as it would be deemed excessive and unwarranted.

“If banned, we have to assume that such platforms are not relevant for the government, whereas the pandemic itself indicates that various state agencies rely on them,” says Nappinai.

There is no legal justification, in the rules or the IT Act, for blocking a service based on non-compliance. It would be immediately challenged and banning would run the ire of judges, says Chima.

What about Twitter’s continuing troubles with law enforcement agencies in India?

In February, Twitter had blocked several handles — that the government wanted removed under Section 69A of the IT Act — and later restored some of them, marking a friction between both sides.

This meant the tech giant calling out censorship in public, says Chima. Secondly, the company has decided to start applying its manipulated media policy, which was created in the US, to tackle disinformation in India including by political figures.

It also applied it against a BJP spokesperson, which led to calls from the government to drop the label and police raid and investigation.

The political context cannot be ignored, says Chima.

“If the government can show a clear example of large amounts of complaints against Twitter, it would justify the rule-making in this case. But it does not seem to be caring about users at all and only trying to increase its power.”

Feature Presentation: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article