Where Jha towered over other historians, was in his fearless evocation of pluralism, dissent and rationality.

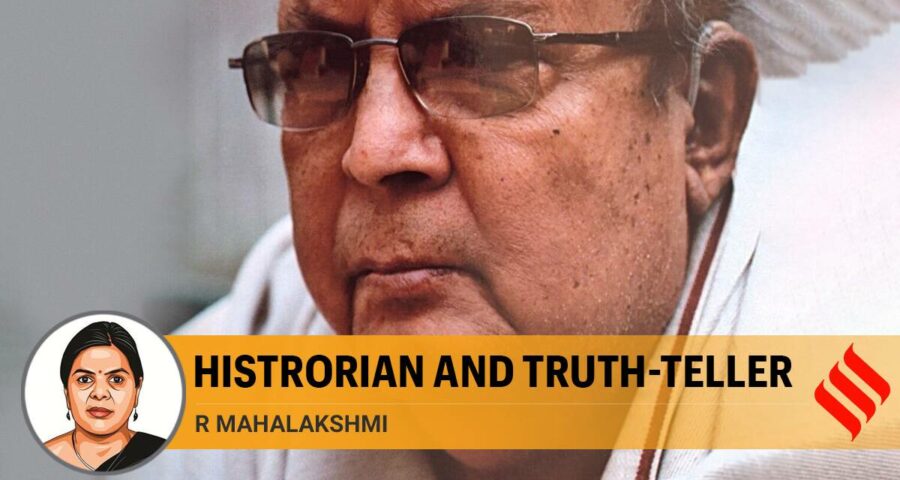

Professor D N Jha (1940-2021), one of the most eminent historians of ancient India, passed away peacefully in his sleep on Thursday. Although suffering from chronic ailments, he never saw himself as incapacitated, and remained active academically until the very end. His last book, an edited volume on the making of alcohol and its consumption in ancient India, came out in January 2020, and his last lecture was delivered online (his written essay was read out) just three weeks ago. With his passing, an era of self-confident academic scholarship in post-Independence India seems perilously close to its end.

Jha graduated from Presidency College, Kolkata, in 1959, and then moved to Patna University from where he completed his MA, and later PhD under the tutelage of the legendary R S Sharma. He became a faculty member at the Patna University, and then moved to the University of Delhi, where he spent the next three decades teaching, researching and writing several important books on ancient Indian economic and social history. Appreciation of the rich sources of ancient Indian history, rigorous analysis and interdisciplinary methods, and scientific and secular history writing were his abiding legacy.

Apart from specialised works on revenue systems or aspects of economy and society in ancient India, his general survey of ancient Indian history, a slim but dense work that has been translated into many Indian languages, remains a favourite with students of history.

Where Jha towered over other historians, was in his fearless evocation of pluralism, dissent and rationality. The historian was beholden to none but the truth, and if that truth was uncomfortable for some sections of society, so be it. The Myth of the Holy Cow was the gauntlet he threw before those who claimed that beef-eating was the “baneful bequeathal” of the followers of Islam to India. First published in 2001, withdrawn due to protests by Hindu communalists, and later published in an international (Verso, 2004) and an Indian (Navayana, 2009) edition, the work flagged several issues: That there was no taboo on beef-eating in the Vedic religion as such; that in caste-ridden Indian society of pre-modern and modern times, beef was the most accessible and nourishing food for the large section of the so-called untouchable classes; that the adherents to the doctrine of ahimsa did not eschew non-vegetarianism; and that the communalising of dietary practices was rooted in contemporary politics alone. Copious references to animals offered in Vedic sacrifice, and descriptions of the distribution, cooking and eating of different types of meat, including beef, from various texts were unambiguous evidence presented by him.

Being a meticulous scholar, he also drew attention to the disapprobation of animal sacrifice right from the Rig Veda down to the Upanisads. Those who demanded that the book be withdrawn had clearly not read it. Wendy Doniger, a scholar of ancient Indian Sanskrit texts, wryly commented in her review of this work that Jha should take the attacks on his book as a compliment, since they seemed to prove that the pen is mightier than the sword! Jha himself was not so sanguine, and often recounted instances of disruption lectures, physical attacks, and death threats. But such was his faith in academic freedom that he refused to recant a single word.

A related and recurring concern for Jha was the projection of modern, politically-motivated stereotypes onto the past. In the past two decades he turned his lens towards the claims of an eternally tolerant and accommodative Hindu identity, of Hindus as stoically withstanding the onslaughts of marauding foreigners. He unequivocally debunked chauvinism in history writing and termed it the first cousin of communalism. While religious and social conflicts in premodern times were discussed in his works, he also pointed out the many instances of syncretism, co-existence and harmony throughout Indian history.

Jha’s death has deprived us of a pillar of strength. He not only provided a strong historiographical direction to the discipline of history but also demonstrated the strength of character to follow that path.

This article first appeared in the print edition on February 6, 2021, under the title “Historian And Truth-Teller”. The writer is professor of history at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Source: Read Full Article