In the run-up to the Delhi march, Ilam Singh recounts how Bharatiya Kisan Union’s Mahendra Singh Tikait extracted concessions on paini ki thod pe (on his own terms) from district administrations and political leaders in Meerut, Shamli, Muzaffarnagar and other parts of UP

His memory plays hide and seek with dates and days. But the images of the 1988 Delhi protest by farmers are still fresh in his mind: a sea of white stretched from India Gate to Vijay Chowk, the lifeless body of a farmer on an ice slab, horse-mounted police chasing tumbling protesters, an emotional Mahendra Singh Tikait when police tried to evict the crowd and Rashtriya Lok Dal chief Ajit Singh stepping up to protect Tikait.

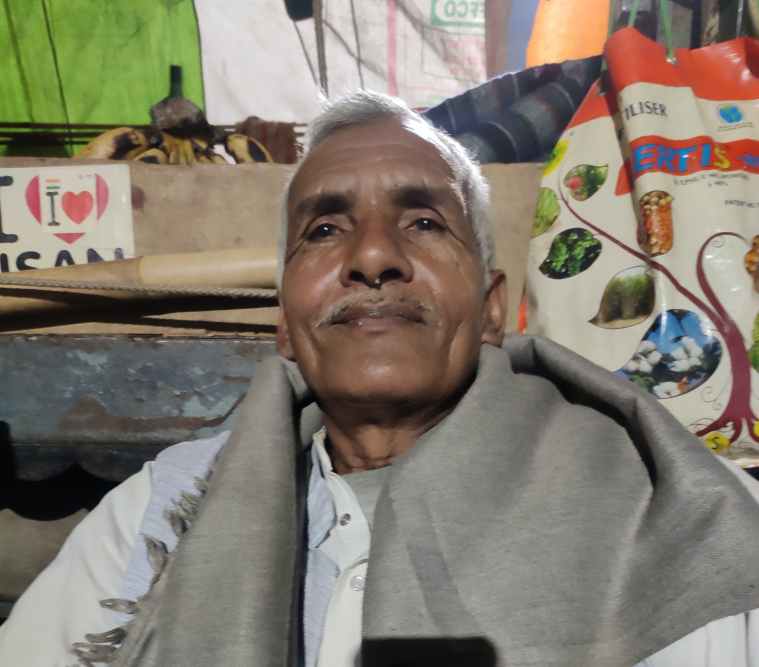

Thirty-two years later, Ilam Singh (93) from Meerut is back where he likes to be: in the thick of an agitation at the Ghazipur border where farmers have been protesting for more than two months against the three farm laws. Singh was one of Tikait’s confidantes and saw the 1988 movement for waiver of power bills and clearing of sugarcane dues up close.

In the run-up to the Delhi march, he recounts how Bharatiya Kisan Union’s Tikait extracted concessions on paini ki thod pe (on his own terms) from district administrations and political leaders in Meerut, Shamli, Muzaffarnagar and other parts of UP. One of the methods of negotiation was playing good cop, bad cop. “Once we ghaeroed a sugar mill in Meerut, demanding farmers’ dues. Follow Chakka Jam LIVE Updates here

Tikaitji confided in me: “Chaudharyji, I will ask you to withdraw the protest, but you must refuse to budge until the sugar mill pays. You should insist on a date by which the due will be paid.’ The sugar mill had no option but to clear our dues the same days,” Singh chuckles.

Singh, who was former BKU treasurer and Meerut district chief, says farmers believed in Tikait because of his rustic delivery of speeches, defiance and simple living. “That’s why lakhs joined him in 1988.”

“We reached Delhi by tractors and trains. The Rajiv Gandhi government tried all tricks to evict us. But for Tikait’s resolve, all efforts were met with resistance. During our protest, the police finally decided to arrest him. Horse mounted police lathicharged us. Tikait could not see this and broke down. When Ajit Singh was alerted about the crackdown, he came running to the site and protected us, ensuring the protest continued,” says Singh.

RLD general secretary Trilok Tyagi, who was party’s youth wing president at the time, says Ajit Singh always stands by farmers and has lobbied with the government on their behalf.

Of the two protesters who died during the Boat Club protest, Ilam Singh identifies one of them as Baghwan Singh. “His body lay on the ice slab for two days. The government refused permission to cremate him there. However, Tiakitji decided to go ahead with the funeral. The funeral pyre was made of sandalwood to recognise his sacrifice,” he recollects.

He says the source of Tikait’s decision-making and indomitable spirit was his morning prayers. “He would wake up at 4 and pray to God. He would also ask us to do the same and listen to the divine call for selfless service and better decision making.” Despite his devotion to his religion, he never disrespected others and the BKU had leaders from all religions. “He used to say: First, we are farmers then Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs or Christians.”

He asserts that the ongoing protest at the Ghazipur border is bigger and more inclusive than the one in 1988. “Compared to 1988 when farmers mostly from Uttar Pradesh laid siege in Delhi, today people from across the country have joined the protest here.”

A few others who participated in the Boat Club siege say the 2012 Muzaffarnagar riots and political plunge by Tikait’s son Rakesh had dented BKU’s secular image. “After Rakesh’s emotional appeal following the January 26 violence, all religions have once again united to challenge the black farm laws,” says a farmer from Muzaffarnagar.

Comparing Tikait Senior with his sons, Ilam Singh underlines: “They can’t emulate the charisma of their father. Nevertheless, they are back on track.” He suggests that a union leader should abstain from politics. “The reason is if you join a party, you can’t speak against it. You are tethered to its ideology. The bare minimum required from a farmer leader is the apolitical nature of the protest,” he says.

On the stand-off with the central government and farmers, Ilam Singh says that they have to stand their ground and should be ready for a long haul. “Hum to 2023 tak taiyar hain. (We are prepared until 2023).”

For Sobir Singh, who also took part in the Boat Club protest, the most abiding image of Tikait Sr is his fleeting movements. “One second, he would be seen sucking hookah. The next moment, he was found in the middle of an intense discussion over agriculture issues. The key takeaway is neve stand still. Keep moving. Keep mobilising in the interest of farmers,” says the 63-year-old farmer.

Source: Read Full Article