Directives regarding who wears what has come up on several occasions in the Indian past, including those imposed by Gandhi himself. What politicians must wear was also briefly discussed in the Constituent Assembly.

Vimal Chudasama, the Congress MLA from Somnath constituency, was evicted from Gujarat Assembly by Speaker Rajendra Trivedi for coming to the House wearing a T-shirt. Chudasama, who was wearing a pair of blue jeans and a black t-shirt, with the words, ‘free spirit’ on it, responded that he had won votes campaigning in this attire. His party too opposed the Speaker’s decision arguing that there were no rules regarding how a legislator should dress in the Assembly. Nonetheless, the Speaker refused to budge, stating, “Because you are an MLA, you cannot come to the House in any manner, in any clothes. This is not a playground. You are not on a vacation. There is a protocol of uniform.”

It is true that there are no rules with regard to the attire of a political leader in Parliament or any Assembly. However, it is also a fact that clothing has always been a matter of political statement. Who can forget the furore when Mahatma Gandhi walked into Buckingham Palace to meet King George V in a dhoti and shawl? It was a strategic act by Gandhi to identify with the poorest of Indians. But directives regarding who wears what has come up on several occasions in the Indian past, including those imposed by Gandhi himself. What politicians must wear was also briefly discussed in the Constituent Assembly.

The politics of what to wear in pre-independence India

In medieval India’s Mughal domains, the ruling elite had insisted on the adoption of Mughal styles of clothing by all officials in the government. Social anthropologist Emma Tarlo in her book, ‘Clothing matters: Dress and identity in India’ notes: “This had forced many elite Indians into Mughal dress in the public sphere. As a strategy of resistance, most Hindus used to remove their foreign apparel before entering their own homes, thereby distinguishing their imposed identity from their chosen identity.”

This was not the case with the British though, who preferred to look and dress differently from the local populace. “In their dress and demeanor they constantly symbolised their separateness from their Indian superiors, equals and inferiors,” writes anthropologist Bernard Cohn in his article, ‘Cloths, clothes and colonialism: India in the nineteenth century’. In 1830, a legislation was introduced banning all members of the East India Company from wearing Indian clothes in public functions. English writer Aldous Huxley had observed the British dependence on clothing rituals in the following words: “It is as though the integrity of the British Empire depended in some directly magical way upon the donning of black jackets and hard boiled shirts” — as cited in Tarlo’s book.

Often these rules of sartorial choices were deemed rather uncomfortable by most British who found the climate in India unsuitable for garments like kid or suede gloves.

The British obsession with their clothes was driven more by the fact that a certain section of the Indian population, particularly the educated elite, had taken a liking towards European dress and manners. This was further linked to the problem that the British did not want Indians to adopt European fashion but wanted them to buy and wear British manufactured textiles. For the British, the dress of the Indians posed an ethical dilemma. “On the one hand they felt their duty to civilise barbaric natives and rescue them from their own primitiveness,” writes Tarlo. “But on the other hand the British did not want the natives to become too civilised.”

Tarlo narrates an incident from the life of the Bengali poet, writer and dramatist, Michael Madhusudan Dutta that best illustrates the British policy towards Indian dressing. Dutta was sent to Bishop’s College in Calcutta where he was given a Western education and developed European tastes as desired by the British. Yet he was discouraged from wearing the same uniform as his college mates did. Dutta devised a plan to trick the British. He appeared in an elaborate Indian outfit of white silk with a colourful turban and shawl. Embarrassed by the choice of clothing, the college authorities allowed Dutta to wear the regular uniform.

With the birth of the 20th century and the waves of nationalism brought by it, a new form of order was brought upon how Indians ought to dress. The Indian nationalist critique of the British government’s policies leading to the impoverishment of India formed the basis of the Swadeshi movement in Bengal starting in 1903. As the movement progressed, there was an increasing amount of discussion and propaganda to encourage Indian weavers and to revive the hand spinning of cotton thread. These ideas were essentially developed and formalised by Gandhi.

“Gandhi continually articulated and elaborated on the theme that Indian people would only be free from European domination, both politically and economically, when the masses took to spinning, weaving and wearing homespun cloth, khadi,” writes Cohn. He notes that during the non-cooperation movement of the 1920s, the wearing of khadi, and particularly the cap which went on to be referred to as the ‘Gandhi cap’ became an act of political resistance.

The movement did have the desired impact on the British. In March 1921, Gandhi reported that several European employers had banned the donning of white khadi caps in office. A month later, in Allahabad, the collector forbade government employees from wearing them. Similar action was also taken in Simla. Khadi, Gandhi argued, had the potential to bring the Raj to its knees.

It was not easy though to convince people to adopt khadi. Most, and especially the elite, had come to equate foreign cloth to bring civilised. Gandhi therefore insisted on the moral obligation to take to Khadi. In an act of building psychological pressure, he emphasised on the transformative quality of the cloth. “The mere act of wearing khadi was so virtuous in itself that it could purify the wearer, whereas foreign cloth was so intrinsically vile that contact with it was physically and mentally defiling,” explains Tarlo. His speeches on the virtues of khadi were so stirring that there were numerous episodes of people stripping themselves off their foreign garments and burning them.

So sure was Gandhi of Khadi’s ability to transform India that when after Independence people were tempted to give up on the cloth, he wrote that Khadi represented a choice of life based on non-violence and that people mistook it to be a mere strategy to attain Independence.

What to wear in an Independent India

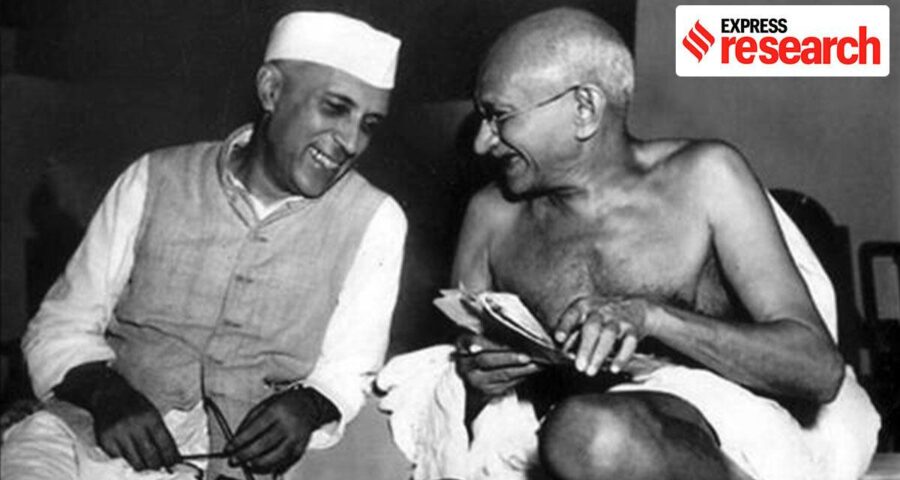

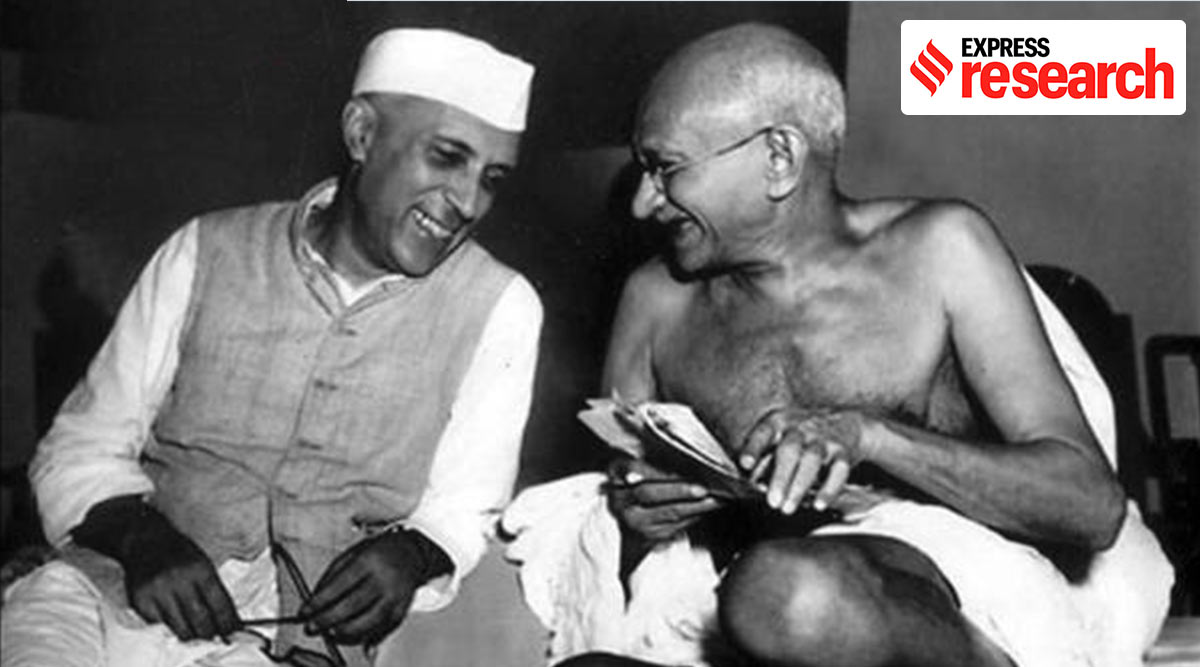

The moral obligation and national consciousness attached to Khadi did not die down after Independence. After fighting for freedom under the Khadi banner, politicians found it difficult to turn away from it. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru chalked out for himself a non-western look stitched out of khadi: tight pyjamas teamed up with long sherwani and what is now famous as the ‘nehru jacket’. “Concerned by the post-independence sartorial confusion around him, Nehru wrote an official note on dress, advising those in higher grades of government office to steer clear of European clothes, which ‘marked them out as a privileged, denationalised and out-of-date class, and to adopt such clothes as would take them closer to the people’,” writes Tarlo.

Nehru’s commitment to a non-European look was passed on to his daughter Indira Gandhi who also would be seen in public mostly in handloom cotton sarees. Rajiv Gandhi too favoured khadi after he entered office in 1984.

The debate over what to wear did come up in the constituent assembly debates as well. On April 29, 1947, Rohini Kumar suggested a ban on discrimination against dress worn by any nationality. “Even today when we are on the threshold of independence there are hotels which do not welcome people dressed in Indian style,” he said. “I am not afraid of the future, because I believe that when India is independent such restrictions would disappear. But what I am afraid of is a reprisal or a revenge taken against such European minded people and people in European dress may not be allowed to come into hotels. For that reason particularly I want that this amendment should be accepted by this House.”

On November 17, 1949 B Das suggested that a national dress must be specified: “I hate to see officials still moving about in ties and collars. Our association with the Commonwealth does not entitle anybody to put on foreign dress. They should be debarred from doing it. Parliament should debar by legislation. Nobody in the employment of the State should wear foreign dress.”

It was Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel whose response came to be agreed upon by most parliamentarians of an Independent India. “Such things as dress cannot be put in the fundamental rights,” he said responding to Chaudhury. “If the world at large should read such provisions in our fundamental rights, then they would naturally conclude that we do not even know how to treat our nationals and how to treat our fellow beings.”

Source: Read Full Article