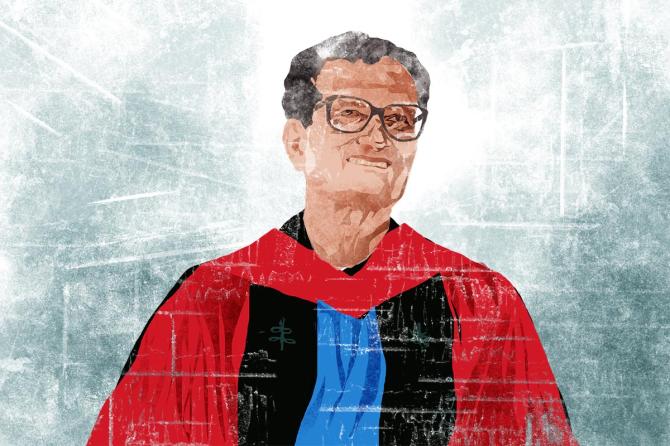

Amartyada, says Omkar Goswami, thank you for being the humane, caring and socially concerned economist that you are.

Born in 1933, Amartya Sen is over 87 years old. At that age, most people of letters tend to relax and ruminate. Not Sen.

With COVID-19 having taken away his incessant travels and lecturing and battened him down at his house in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Sen has written his memoir — which is either his 30th or 31st book, a list that began with his PhD thesis, Choice of Techniques, published by Basil Blackwell in 1960.

This book consists of five parts — comprising a combination of pure memoir with chapters on fundamental philosophical, political or economic issues.

Part One deals with Sen’s early life, from childhood to his schooling at Santiniketan.

It is interspersed with three excellent non-memoir-like chapters on the rivers of undivided Bengal, on Tagore and his arguments especially with Gandhi, and on Sen’s long association with Sanskrit that started under his grandfather’s tutelage in Santiniketan.

I found his chapter on the company of grandparents particularly interesting, especially his close relationship with his maternal grandfather, the Sanskrit scholar, Kshiti Mohan Sen, whose classic, Hinduism, Sen translated from Bengali to English in 1961.

Part Two is thematic. It deals with the devastating Bengal Famine of 1943, the idea of Bangladesh, nationalist political resistance to British colonialism up to the division of India and Britain in India under the Raj.

Part Three returns to the autobiographical framework.

This is after Sen finished school at Santiniketan and moved on to do his BA at Presidency College, Calcutta in 1951.

Living at the YMCA hostel at Mechua Bazar, Sen came into his own — not just in academics but in enjoying a sense of freedom and making many friends in the course of long addas at the Coffee House and elsewhere, covering every topic under the sun.

There is a great story in Chapter 12 that involves Sen, his college friend Sukhamoy Chakravarty, and Dasgupta’s Bookshop which was the bibliophile’s haunt.

Sukhamoy had borrowed Kenneth Arrow’s classic, Social Choice and Individual Values and passed it on to Sen to read.

In it, Arrow set out his stunning ‘Impossibility Theorem’. The question was this: Can individual choices of people be translated into a consistent social choice?

Arrow proved that with four extremely basic conditions that needed to be satisfied, one could not map individual preferences through any non-dictatorial social choice mechanism to yield consistent social decisions. Thus, the ‘Impossibility Theorem’.

This discovery led to what I consider to be the greatest period of Sen’s formal theoretical work which resulted in his masterpiece, Collective Choice and Social Welfare, published in 1970.

Part Three also deals with Sen’s early battle with oral cancer.

In the summer of 1952, when he was not even 19 years old, Sen was treated at the Chittaranjan Cancer Hospital with seven days of gruelling, old-fashioned radium radiation and suffered incredible post-radiation pain; thankfully, the malignant tumour disappeared.

Thereafter, he underwent numerous treatments at the Radio Therapy Centre in Cambridge between 1953 and 1963.

Part Four, consisting of nine chapters, mostly deals with Sen’s first ten years at Trinity College, Cambridge, first doing his second BA degree and then as a Prize Fellow and eventually as a lecturer and staff fellow.

After suffering some introductory sherry parties — a drink he hates with a passion — Sen went to meet his Gods, Piero Sraffa and Maurice Dobb.

Sraffa taught Sen various aspects of economics and the merits of ristretto.

‘What was intended to be a two-year stay at Trinity for a rapidly earned BA degree… ended up being my first period of ten years there, from 1953 to 1963.’

Sen returned to Cambridge in 1998 as the Master of Trinity College, where he served for six years, and where he was when he received the Nobel Prize for economics.

Much of this section is about the deep friendships made — such as Mahbub ul Haq of Pakistan, Lal Jayawardena from Sri Lanka, Michael Nicholson — and Sen’s interactions with Sraffa, Dobb and Joan Robinson; of Sen being elected as an Apostle, an exclusively “small intellectual aristocracy of Cambridge”; and his two-year stint in between as a professor at Jadavpur University so that he could complete the minimum number of years needed to submit his PhD thesis.

Part Five is short, consisting of two chapters: A philosophical one called ‘Persuasion and Cooperation’ and the other ‘Near and Far’, which deals with Sen’s days as a professor at the Delhi School of Economics from 1963 to 1971.

After that he left to take up a professorship at the London School of Economics. The book abruptly ends there.

Which is a pity. Because between 1971 and now, he was at the LSE for six years; at Oxford for eleven; as the Master of Trinity for six; and at Harvard from 1987-88 and then from 2004 till date.

It was also when Sen’s social, ethical and political conscience spoke out like never before. He had much to share about this highly productive period.

Let me end with a personal anecdote. Sen was my D Phil examiner at Oxford in 1982, and we communicated off and on in the pre-Internet days.

In 1989, while at Rutgers, I was re-reading his Poverty and Famines, which demonstrated that the Bengal Famine of 1943 was not on account of any food availability decline (FAD) but solely due to failure in exchange entitlements (FEE).

Looking at the same data that Sen had used, but treating these somewhat differently, I found that there was significant FAD and, hence, FEE.

So, I typed a draft and sent it to him for his critical comments.

Five days later he called back and said, ‘I’ve gone through your paper carefully and checked all your calculations. You are right. Go ahead and publish it.’ Such was, and is, the academic grace of the man.

Amartyada, thank you for being the humane, caring and socially concerned economist that you are. The profession is blessed for that.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article