The proposal of a United Bengal and its rejection thereafter though, was rooted in years of communal conflict that had emerged in the province, especially since the mid-1930s.

On April 27, 1947, the then prime minister of Bengal, H S Suhrawardy, addressed a press conference in New Delhi in which he put forward an idea most unexpected in the historical circumstances of the times. Suhrawardy pleaded for an ‘independent, sovereign, undivided Bengal in a divided India’. Though short lived, the idea was briefly supported by the likes of Gandhi, Jinnah, and a few British leaders as well.

“I promise,” said Suhrawardy, “that the future will be unlike the present. Bengal’s wealth, peace and happiness will benefit a great nation. If the Hindus can forget the past and accept the proposal, I promise to fulfil their hopes and aspirations to the full.” He also stated that an independent Bengal will have its own constitution and a Legislative Assembly that will take decisions for the country. “We Bengalis have a common mother tongue and common economic interests,” he said.

The plan, as Suhrawardy had envisaged, was to have massive implications in the history of India. British India in that case would leave behind not two, but three successor states. Bengal would be a separate dominion alongside India and Pakistan. But this was not to be.

The same Hindus who in 1905 had actively protested against Lord Curzon’s Partition of Bengal, were the ones who now most aggressively sought the Partition of the province. But those few months between April and June 1947 were crucial in deciding the political destiny of Bengal, and that of a post-Independent India. The proposal of a United Bengal and its rejection thereafter though, was rooted in years of communal conflict that had emerged in the province, especially since the mid-1930s.

The days preceding the United Bengal proposal

Political scientist Bidyut Chakrabarty in his book, ‘The Partition of Bengal and Assam,1932-1947: Contour of freedom’ writes that the most significant development in Bengal in the decades preceding the 1947 Partition was the emergence of Muslims as a distinct socio-economic group and their importance in the political arena with the 1932 Communal Award.

British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald explained the Communal Award on the following grounds, as quoted in Chakrabarty’s book: “Separate representation is primarily designed to secure adequate protection for the minorities. it is bound to continue in some form or other until minorities are disposed to trust to majority rule, and until a political accommodation between Moslems and Hindus is reached.”

Consequently, it meant that distribution of seats in the centre and the provincial legislative seats would be done in proportion to the population of minorities. Hindus were in majority everywhere, except in Bengal and Punjab, where Muslims were in larger population. What resulted was the growth of Muslims as a competing power in provincial institutional politics. “Once in power, their representatives adopted several plans and programmes to ameliorate the conditions of the Muslims, exploited over generations by the Hindus,” writes Chakrabarty.

In the aftermath of the 1937 elections, the Krishak Praja Party (KPP) and the Muslim League formed a coalition government in Bengal. They took a number of legislative steps to improve the condition of the Muslims in the state, thereby drawing the wrath of the Hindu community. “When the Bengal Tenancy (Amendment) Act (1938), for instance, abolished abwabs, the landlord’s transfer fee, and their right of pre-emption, and the Bengal Agricultural Debtors Act (1939) established arbitration boards to enable the debtors to obtain moratoriums, Hindu politicians both within and outside the legislature characterised them as well-engineered devices to squash the Hindus,” writes Chakrabarty.

With the 1946 general elections being won by the Bengal provincial Muslim League, Suhrawardy was appointed prime minister. Save for one, everyone else in his cabinet were Muslim League members. Historian Nitish Sengupta in his book, ‘A History of the Bengali-speaking People,’ writes that the formation of Suhrawardy’s cabinet without a single upper caste Hindu was a “strong message to them that the government was determined to rule Bengal without associating with the bhadralok class.”

“For them this was a foretaste of what was likely to happen to them if the whole of Bengal went to Pakistan,” writes Sengupta.

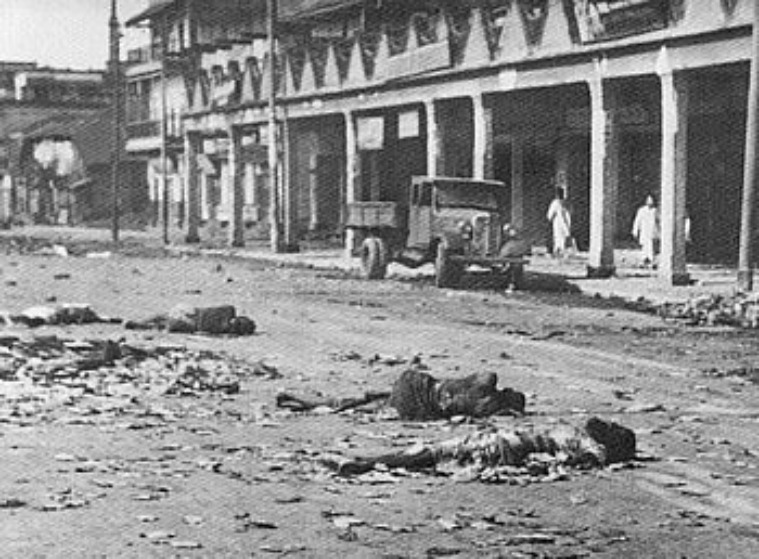

What further aggravated the situation was the communal violence in Calcutta in August 1946 and that in Noakhali seven weeks later. The riots were triggered by a nationwide protest by the Muslim community called by Jinnah. The Direct Action Day as August 16 was called, was declared a public holiday by Suhrawady’s government in Bengal. “Whether or not Suhrawardy had a sinister design in mind it is difficult to say. But many contemporaries believed that the clear object of calling a hartal on that day was to enable the murderous gangs to identify for attack those shops and establishments that opened their shutters in defiance of the hartal and were, by implication, not Muslim-owned,” writes Sengupta.

The scars of the riots were felt by the city for many days afterwards. For a long time Calcutta was divided between Muslim and Hindu zones with very less cross-movement between them. Historians of Bengal believe that the Calcutta riots of 1946 were by far the most cataclysmic event leading to the Partition of the province a year later.

The proposal to partition Bengal on religious lines, like that in Punjab, was first taken in the Tarakeshwar Conference of the Bengal Provincial Hindu Mahasabha between April 4 and 6, 1947. One of the principal advocates of this was Syama Prasad Mookerjee, who declared: “I conceive of no other solution to the communal problem in Bengal than to divide the province and to let the two major communities residing here live in peace and freedom (as quoted in Sengupta’s book).”

The idea found support from other stakeholders as well. On April 1, 1947, 11 members of the Constituent Assembly from Bengal submitted a memorandum to the Viceroy supporting the Partition of the province. The Marwari business community in Calcutta, led by G D Birla, too lent strong support to the proposal. Fifty jurists of the Calcutta High Court came out with a statement alleging that if Bengal went to Pakistan, then Bengali Hindus would be trading one form of slavery for another.

The proposal of the United and independent Bengal

The widespread demand from Bengali Hindus to partition the province came as a surprise to Suhrawardy. It was in this context that he conceived of an alternative plan, that of keeping Bengalis United and independent from both India and Pakistan. For Suhrawardy, a Pakistan without Calcutta was absolutely unacceptable. He even envisaged a joint electorate in an independent Bengal to allay the fears of the Hindu community.

“Suhrawardy, according to P S Mathur — at that time his press secretary — had envisaged that the proposed, undivided, independent Bengal would include the districts of Manbhum, Birbhum and Purnea from Bihar and the Surma Valley of Assam, with the result that there would not be substantial difference in the numerical strength of the Hindus and the Muslims,” writes Sengupta.

Suhrawardy’s idea found takers among people like Sarat Chandra Bose and Kiran Shankar Roy who were opposed to the Partition of Bengal. It also resonated well with many Bengali Muslims. Abul Hashim, the secretary of the Bengal Provincial Muslim League, along with Suhrawardy pointed out the perils for Bengali Muslims joining Pakistan: “In an Akhand Pakistan they would be under the domination of West Pakistanis and Urdu would be the state language. They could not expect a better position than becoming peons under the Urdu speaking judges and magistrates (as quoted in Chakrabarty’s book).”

Although the United Bengal proposal went against Jinnah’s two-nation theory, Suhrawardy was confident of getting the former to agree that Bengal need not join Pakistan, if it decided to stay United and independent. Jinnah did come out strongly in favour of a United Bengal. “What is the use of Bengal without Calcutta? They had much better to remain United and independent; I am sure that they would be on friendly terms with us,” he is noted to have said in a conversation with Mountbatten on April 26, 1947.

Writing about Jinnah’s support to a United Bengal, Chakrabarty explains: “Jinnah was impressed with Suhrawardy’s scheme, probably because it was a stepping stone towards attaining a greater Pakistan comprising provinces in which Muslims constituted a majority.” Jinnah also agreed with Suhrawardy that the survival of East Bengal by itself was not economically viable since almost all coal mines, minerals, factories, jute processing mills were in West Bengal.

Bose along with Suhrawardy and Hashim also approached Gandhi on several occasions with the proposal for an undivided Bengal. Gandhi did lend half-hearted support, but advised them to gain the trust of the Hindus first.

On May 24, 1947, the proposal was made public. According to the plan, independent Bengal would decide its relations with the rest of India; there would be joint electorates and adult franchise with reservation of seats for Hindus and Muslims based on their population; an intra-communal ministry in which Hindus and Muslims would have equal share; Hindus and Muslims would have equal representation in all services including military and police; and a 30-member constituent assembly would be formed to draft the future constitution of Bengal.

The plan did receive the support of the British as well, who saw in it a better prospect to protect their commercial interests in Calcutta. On May 8, when Mountbatten tabled the Partition plan, he made an exception for Bengal, which he argued would be allowed to remain independent if it chose so. The British Prime Minister Clement Atlee too hoped that Bengal would decide to remain United.

The rejection of the United Bengal proposal

The strongest opposition to a United Bengal came from the Hindus of West Bengal who were in no mood to accept Muslim domination in politics in an undivided Bengal, after experiencing two decades of Muslim reservations in government jobs.

The Congress leadership was also clear in not providing support to the United Bengal plan. At a meeting on May 23, when Mountbatten raised Suhrawardy’s plan, Nehru made it very clear that the Congress would accept a United Bengal only if it decided to stay inside the Indian Union. “He (Nehru) warned the Bengali Hindus not to be misled by Suhrawardy; an independent Bengal would mean the dominance of the Muslim League and practically the whole of Bengal going into the Pakistan area,” notes historian Ayesha Jalal in her book, ‘The sole spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the demand for Pakistan’. “So although Mountbatten had persuaded London to make an exception for Bengal and allow it to remain an independent dominion, he quickly dropped the plan once Nehru had rejected the proposition out of hand,” she adds.

Bose was aware that without the support of the Congress high command, it would be practically impossible to go ahead with the plan of a United Bengal. Further, dissensions arose between him and Suhrawardy who was unhappy with the prospect of disallowing separate electorates. “The introduction of a joint electorate would, he (Suhrawardy) was reported to have expressed, eclipse the Muslim preponderance in the legislature in the long run,” writes Chakrabarty. Eventually, Bose too withdrew from the United Bengal campaign.

But it was the Hindu Mahasabha, in particular its leader, Mookerjee, who was fiercest in his opposition to the United Bengal scheme. Writing to Mountbatten in May 1947, Mookerjee argued that Bengali Hindus had suffered terribly during the last ten years on account of ‘communal misrule and misadministration.’

“If ever an impartial survey is made of Bengal’s administration during the last ten years, it will appear that Hindus have suffered not only on account of communal riots and disturbance, but in every sphere of national activities, educational, economic, political and even religious,” he wrote, as reproduced in Chakrabarty’s book.

Mookerjee also argued that the United Bengal scheme went against Jinnah’s two nation theory, which stated that Hindus and Muslims are two separate nations and therefore Muslims needed to have their own homeland. Therefore, Mookerjee argued that Hindus of Bengal who comprised half of the province’s population must also not feel compelled to live within a Muslim state.

Consequently, an opinion poll conducted by the Amrit Bazar Patrika among the literate Hindus and Muslims of Calcutta and other district towns showed that more than 98 per cent favoured the partition of Bengal and a mere 0.6 per cent was in favour of an independent province.

Thereafter, the movement for a third dominion soon lost steam. With the announcement of the Partition plan on June 3, 1947, the saga of a United Bengal drew to a close.

Further reading:

The Partition of Bengal and Assam,1932-1947: Contour of freedom by Bidyut Chakrabarty

A History of the Bengali-speaking People by Nitish Sengupta

The sole spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the demand for Pakistan by Ayesha Jalal

Source: Read Full Article