But their trajectory and direction have been largely influenced by politics and the political leadership’s understanding of how the economy needs to be managed, explains A K Bhattacharya.

Thirty years ago, a finance minister who was yet to become a member of Parliament ushered in a series of bold reforms that dramatically altered the course of economic policy making in India.

No less dramatic was the way most of those reforms were initiated in the first 100 days of that government to bail the Indian economy out of an unprecedented fiscal and balance of payments crisis.

Neither did the government enjoy a majority in the Lok Sabha, nor was its prime minister, just like the finance minister, a member of Parliament, while they took those big-bang decisions.

Such was the enormity of the crisis that few questions about the political propriety of such decision making were raised.

The prime minister entered the Lok Sabha through a by-poll later in November 1991 and his finance minister became a member of the Rajya Sabha around the same time, representing the state of Assam.

Yes, we are talking about P V Narasimha Rao, who led the Congress government from 1991 to 1996, and his finance minister, Manmohan Singh.

The duo was virtually unstoppable as far as reforms were concerned in the first 100 days of that minority government.

Less than a fortnight after its formation, Singh depreciated the Indian currency against the US dollar by 9.5 per cent on July 2 and followed up with another depreciation by 12 per cent a day later.

The two-stage downward adjustment in the value of the rupee was not a step taken in isolation.

Nor was the burst of reforms led by only Singh and Rao.

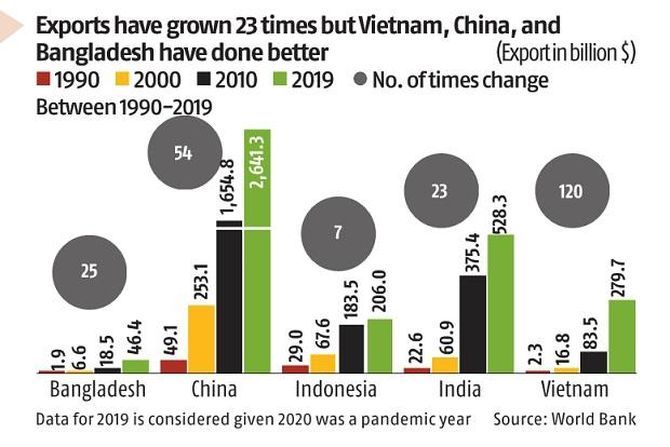

P Chidambaram, commerce minister at that time, also unveiled a bold package of trade policy reforms.

Indeed, on the same evening of the second phase of depreciation, Chidambaram abolished export subsidies like the system of providing cash compensatory support to exporters; removed supplementary licences, which used to help exporters with import facilities; and divested the state trading corporations of their monopoly over the import of a host of goods (also described as decanalisation).

In addition, he scrapped replenishment licences, issued to exporters and with which they could undertake duty-free imports.

Instead, exim scrips were introduced, which were to be issued to exporters and were tradeable in the market.

Over the next year or two, exim scrips would be replaced by a liberalised exchange rate management system.

Initially, this allowed exporters to convert only 60 per cent of their dollar earnings at a market-linked exchange rate and the rest at the official exchange rate, which was much lower.

By March 1993, the government introduced a unified exchange rate, linked to the markets.

Exporters could convert their entire dollar earnings at the market-linked exchange rate.

Even as the Indian currency stood depreciated and the trade policy was reformed to make exports more competitive, Singh had a bigger challenge to face.

India’s foreign exchange reserves had fallen to just about $1 billion in the first week of July, barely enough to meet three weeks’ imports.

To complicate matters, non-resident Indians had begun withdrawing their deposits, making the foreign exchange reserves situation even more precarious.

The finance minister decided to pledge gold kept with the Reserve Bank of India.

Between July 6 and 18, gold was taken out of the vaults of the RBI, shipped to London, and pledged with the Bank of England in three separate rounds, helping the government secure loans of about $600 million.

On July 24, Singh presented his first Budget. Outlining a road map for the economic reforms needed in the coming years, the Budget decided to implement an ambitious fiscal deficit reduction plan.

From a fiscal deficit of 7.6 per cent of GDP in 1990-1991, Singh reduced it to 5.4 per cent in 1991-1992.

This was the steepest ever reduction achieved in a single year.

Equally important was a document that was laid on the table of Parliament, outlining industrial policy reforms and fundamentally changing the way Indian companies would do their business in the coming years.

Industrial licensing was abolished for all sectors except 18 specified groups.

The asset limit for companies governed by the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act was abolished in one stroke.

The monopoly of the public sector was drastically cut, allowing the private sector to enter as many as 10 sectors previously out of its bounds.

Automatic approval for foreign investment up to 51 per cent equity was allowed in 34 industries.

Private companies were freed from the requirement of obtaining the government’s permission for entering into technology agreements with foreign enterprises.

Most importantly, a policy on gradual divestment of government equity in public sector units was announced.

More reforms were introduced a couple of years later in the financial sector, based on the recommendations of the committee headed by M Narasimham, former governor of the RBI, paving the way for new private-sector banks and the phasing out of development financial institutions.

Further reforms in fiscal, trade, and industrial policies were carried out in the following three decades.

But the pace of reforms initiated in those 100 days remains unparalleled till today, possibly because the crisis the Rao government faced in 1991 was also unprecedented.

But the template created for reforms in these sectors has by and large been followed in the following three decades by all the governments and their finance ministers.

Thus, all finance ministers have stuck to the path of fiscal consolidation even though the quality of their commitment to the goals has varied.

The idea of the Centre seeking an end to direct borrowing from the RBI through ad hoc treasury bills was mooted by Manmohan Singh in 1994, but was implemented in 1997 by Chidambaram, who was then finance minister in the United Front government.

Direct tax rates were rationalised with a three-slab structure, with the peak rate being 30 per cent in 1997.

That structure remains intact even today, though attempts have been made to rationalise it further.

On the indirect tax front, Yashwant Sinha, finance minister in the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government between 1998 and 2002, rationalised the rates into fewer broad slabs and expanded the scope of the modified value-added taxation scheme to cover more sectors, which benefited the businesses and the economy in many ways.

That process led to the demand for introducing a goods and services tax system and after a long wait and considerable debate, GST was introduced by Arun Jaitley during the first tenure of the Narendra Modi government in 2017.

The implementation of GST was clumsy and the imperfections in the new indirect tax regime have denied the Indian economy the usual benefits that such a system normally yields.

Industrial policy has broadly followed the course outlined by the Rao government in 1991, with more delicensing, easier foreign investment norms, increased role for the private sector, and more disinvestment of government equity in public sector units.

The Vajpayee government tried out with privatising about a dozen units, but that experiment met with political resistance.

The Narendra Modi government has revived the idea of privatisation, but its implementation has so far been slow.

No fresh privatisation has been completed since the Vajpayee government ended its tenure in 2004.

There have been deviations too from the path of reforms that were ushered in with a bang in 1991.

The reforms agenda for trade policy has met with some resistance and import tariffs have begun to rise from 2018 onwards.

The Modi government’s economic agenda of building a self-reliant India (Aatmanirbhar Bharat) has meant not only a rise in import tariffs for some goods but also the return of a discretionary incentive system to encourage investment in different sectors of the economy.

The proposed policy for the e-commerce entities has provisions that threaten to reintroduce an inspector raj, banished some years ago from most businesses.

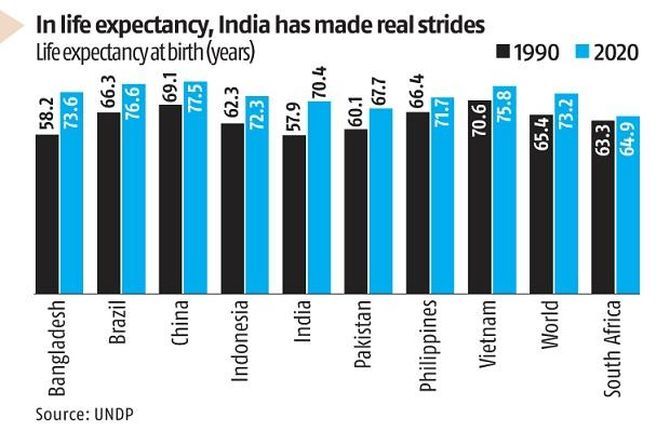

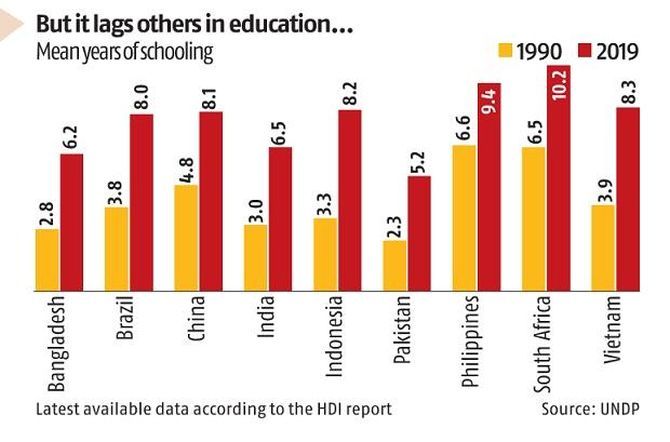

Reforms of 1991 did change the course of economic policy making in India.

The broad contours of the evolving reforms have broadly remained the same.

But their trajectory and direction have been largely influenced by politics and the political leadership’s understanding of how the economy needs to be managed.

Source: Read Full Article