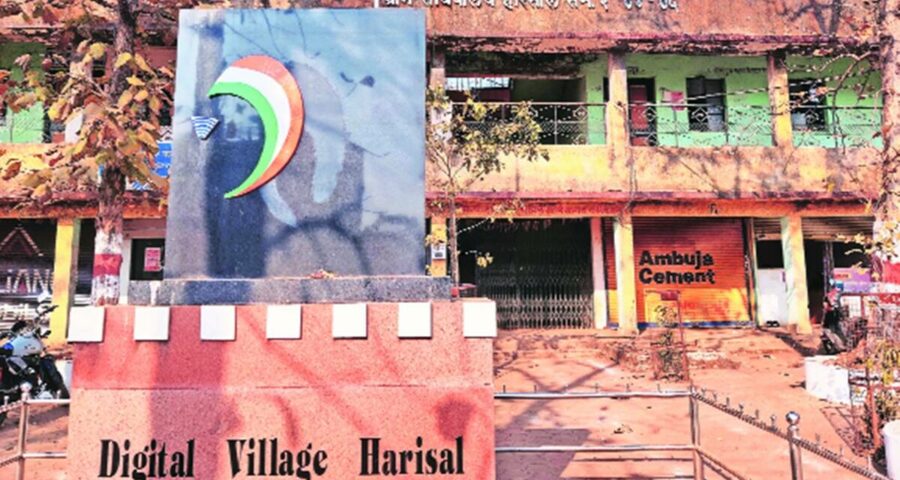

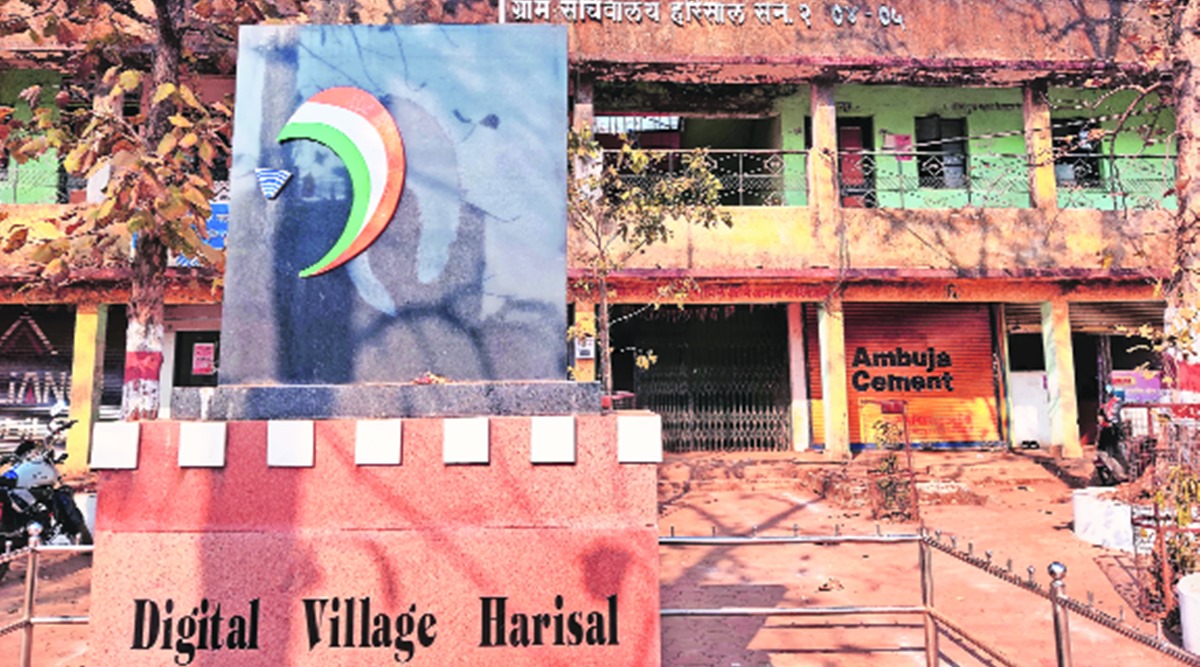

From want of funds to negligence, the district has lost its digital tag in the last four years. Grocery shopowner Manish Meshram joked that tribals now call Harisal an "ex-digital village".

In 2016, Harisal in Amravati became the first digital village on India’s map. But when Covid-19 pandemic made digital technology a necessity last year, the village could not fully utilise it – 40 per cent students in its school could not attend online classes and a much needed tele-medicine service was shut.

From want of funds to negligence, the district has lost its digital tag in the last four years. Grocery shopowner Manish Meshram joked that tribals now call Harisal an “ex-digital village”.

“In the CMO, the war room had the responsibility of ensuring that this becomes a sustainable model. If these services were suspended or the project canned, the current regime has to answer questions… what is its plan to reform villages on a mass scale,” said former Maharashtra chief minister Devendra Fadnavis.

Harisal and over 300 villages in Melghat are infamous for high malnutrition. In 2015, under the Digital India campaign, Fadnavis had decided to use technology to transform Harisal after meeting Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella. Fadnavis said the idea was to “use technology to solve an over a decade-long issue related to malnutrition and overall lack of development by connecting the village to global opportunities”.

Maharashtra government worked with Microsoft, Hewlett Packard, National Informatics Centre, Tata Trusts, Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited and Dayalbagh to touch upon education, health, agriculture and government services. The zilla parishad school was fitted with seven computers to offer information and communication technology training to students who are either in college or have cleared Class XII. A computer and web cam were fitted in the primary health centre (PHC) to serve as a tele-medicine centre; workers at grocery and mobile phone shops were taught how to offer cashless transaction; an automated agriculture-aid messaging system for farmers was installed; an office was set up to aid tribals in accessing government schemes and a free WiFi service was offered to the village with a population of over 2,000.

But the WiFi service was free for only a year. Since 2017, private service provider AirJaldi is charging Rs 100 per month as several villagers complain of slow connectivity. The Indian Express visited the zilla parishad school and found the computer training centre shut even as the school had reopened from January 27. “There was a special teacher assigned to give computer training. But he has not returned to the village since the pandemic began,” said Gajanand Gharot, a teacher.

Data shows that of the 207 students from classes I to VII, only 126 could register for online classes in 2020. “Either students had no smart phone or there was no network. Not everyone can afford to buy data packs and WiFi connection is poor except around the gram panchayat office,” headmaster Kalchand Chauhan said. He added that children who attended online classes would huddle around a phone if network was available. “In these hills, mobile network is a huge problem.”

A road uphill from the school leads to the PHC where a white container-like structure installed by HP stands locked – no staffer remembers where the keys are.

The district health office said that the tele-medicine unit last operated in September 2019. From 180 tele-medicine sessions with neurologist, dermatologist, ophthalmologist, gynaecologist and paediatrician in 2017, the sessions dipped to 138 in 2018, 20 in 2019 and none in 2020.

While broadband facility is available, the technical operator and the dedicated doctor to run the tele-medicine unit is not. “There was never a permanent post sanctioned for tele-medicine unit by the previous or current governments. We did not have funds allocated for maintenance. The last MBBS doctor deputed in 2019 left within months,” said District Health Officer Dr Dilip Ranmale.

The tele-medicine facility remained shut entirely last year even as Maharashtra pushed for the service through e-Sanjeevani portal, as the best means to treat patients not suffering from Covid-19. The unit, thick with dust, fixed with a computer, web camera, air-conditioner, chairs and table will most likely be shifted to another remote village, said Amravati Collector Shailesh Naval. He added that 10 km from Harisal, Sewagram hospital offers specialised services and a tele-medicine unit may not be needed anymore.

Narendra Kalmegh, who worked as a tele-medicine operator until September 2019, said that even before the centre was shut, it ran with hiccups. “Patients could speak with doctors in Mumbai, Hyderabad and Amravati from here. But the process was not that easy. Several times, doctors were not available.”

Mahesh Patil, the Block Development Officer, said the failure of Harisal as a digital village is due to “network connectivity problem in the hills”.

Deputy Sarpanch Ganesh Yevle said that Microsoft’s contract to maintain the digital system was extended from one to three years. “But when the government changed, the contract was not renewed. The Microsoft manager left our village. Eventually, villagers stopped using government services online.”

The gram panchayat office was allotted Rs 1.07 lakh for maintenance of equipment, of which Rs 25,000 is yet to be disbursed. Most funds were used in computer repairs. In the e-assistance office near the gram panchayat, technician Deepak Shervare sits idle. “Earlier, all documentation works and citizen services were carried out from here. Now, we only do gram panchayat office work here.”

Tribals have a wide range of complaints. Take Priya Kajdekar for instance. Every time she wants to use WiFi, she walks down to the gram panchayat office to use it for free. “Airjaldi WiFi is chargeable and offers slow connection,” she said. Since 2015, when there were no WiFi and Internet subscribers, the village had recorded 644 Internet users by 2018. Yevle said the figure has now most likely touched 1,000 but the number of WiFi users have declined and personal data pack users seen a rise.

Collector Naval said that dependence on WiFi has to reduce and mobile networks have to be strengthened. “We are going to set up more towers for Reliance and BSNL to improve network across Melghat. Digital services will automatically improve,” he added.

Source: Read Full Article