The high priest of gossip that stars couldn’t resist: After his death at 102, a glittering farewell to Donald Zec, who shared John Lennon’s honeymoon bed, made Marilyn Monroe giggle, and drove Liz Taylor to a foul-mouthed outburst

Sitting in the first-class cabin of a plane flying to Phoenix, Arizona, in 1956, were an unlikely looking pair.

In one seat was the dazzling blonde Marilyn Monroe, on her way to the set of the film Bus Stop. Sitting beside her was a short, bald man with a London accent.

When their inflight meal was served, Marilyn pushed her tray away, saying: ‘I have to watch my figure.’

Quick as a flash her companion said: ‘You eat, Marilyn, I’ll watch your figure.’

It was a quip that earned him a playful slap on the arm but nothing more because Donald Zec, a showbusiness writer for the Daily Mirror, was by then an intimate of the biggest names in Tinseltown. He criss-crossed the Atlantic in search of Hollywood gossip at a time when there was no impenetrable wall of publicists and minders to block access to the stars.

As he put it, he was ‘by turn war reporter, voyeur, ringside commentator and marriage guidance counsellor’.

Zec, who has died aged 102, was one of the last remaining links to Hollywood’s Golden Age, interviewing such Hollywood legends as Cary Grant, Grace Kelly, James Dean, John Wayne, Mae West and, of course, Monroe.

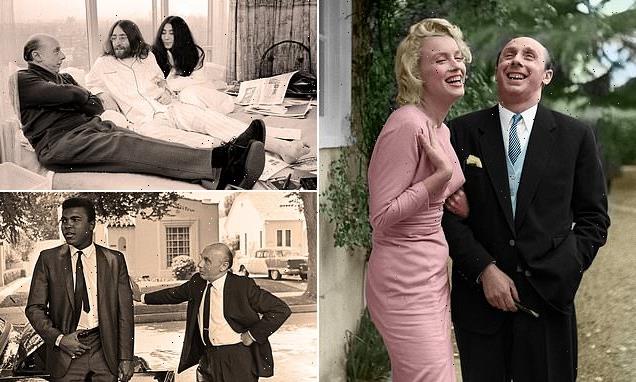

When Marilyn Monroe was plagued by insecurities and heartbreak, it was to Zec that Marilyn turned, once phoning him at 3.30am to share her woes. Pictured: Donald Zec with Marilyn Monroe in June 1960

When she was plagued by insecurities and heartbreak, it was to Zec that Marilyn turned, once phoning him at 3.30am to share her woes. He, in turn, called to console her when she miscarried during her marriage to playwright Arthur Miller.

He also had a close-up view of the fiery relationship between Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton and in his efforts to keep his readers entertained did not always endear himself to his subjects.

He obviously went too far with Taylor because, sitting in her Rolls-Royce, he recalled her turning to him and sneering: ‘You know, you are a little s**t.’

Burton was no fan either. After inviting Zec to lunch with him, Taylor and designer Valentino in 1971, the Welshman wrote in his diary later that Zec was ‘completely out of his depth’.

Perhaps he was intimidated by Taylor. She once answered the door in her nightie when he arrived to interview her. ‘He said she was the most beautiful thing he’d ever seen,’ according to his niece.

It was all a far cry from Zec’s unglamorous origins in an insalubrious part of West London, one of 11 children of immigrant parents. It was his father, Simon Zecanovskya, a Jewish tailor from Ukraine, who shortened the family name to Zec.

The young Donald wanted to be a concert violinist but instead, after leaving school, he took a job with an estate agent, then sold advertising space for The Floor Coverings Review — ‘a pulse-quickener if ever there was one’, he joked, before becoming a messenger boy on the Evening Standard.

He moved to the Mirror in 1938 but his career was interrupted shortly afterwards by the war.

When he returned to the Mirror as crime reporter in 1945, he soon exhibited the nose for a story that was to make his name.

Donald Zec (right) speaks to John Lennon and Yoko about their seven day event at the Amsterdam Hilton Hotel in March 1969

With the police gathering outside in preparation for an arrest, Zec interviewed John George Haigh, the Acid Bath Murderer, over tea at the Onslow Court Hotel, the very place where Haigh had murdered his last victim.

‘He poured the tea saying, ‘Shall I be Mother?’ ‘ Zec recalled. ‘I had tea with him knowing the police had evidence he not only killed people, but drank their blood.’

From crime reporter he switched to royal correspondent — ‘a natural progression’, he joked.

But it was when he started writing about film in the heyday of Hollywood that Zec made his name. These were the days when showbusiness reporters enjoyed generous expense accounts, first-class air travel and luxury hotels.

Zec found himself flying back and forth to Los Angeles on a weekly basis. ‘In one week, I would see Gary Cooper, Spencer Tracy, Marlon Brando and Humphrey Bogart, the thoroughbreds of Hollywood at the time,’ he recalled.

He and Bogart, whose customary greeting was ‘Hey, Limey’, became firm friends. Once, within 20 minutes of checking into the Beverly Wilshire hotel, he got a call from the Maltese Falcon star from the hotel reception, chiding him for failing to call him the moment he arrived. Zec duly spent the weekend on Bogart’s yacht with Lauren Bacall and other stars and was even invited to help celebrate Bogey’s stag night.

Yet Zec retained a healthy degree of journalistic detachment. When he was once insufficiently gushing about Frank Sinatra, the singer sent him a telegram saying: ‘I thought you were my friend, but as of this morning, you blew it.’

And singer Mario Lanza reacted to a disobliging profile by sending him a tea-chest filled with loo rolls with the message: ‘Dear Donald, these foolish things remind me of you.’ Kirk Douglas, aware of Zec’s sometimes acerbic style, urged him to ‘put the knife in gently’ which became the title of his autobiography published in 2003. Zec would rhapsodise about screen goddesses, describing Jane Russell’s ‘bosomy immersion’ in the film Underwater and blonde bombshell Jayne Mansfield, ‘bursting out of a vermilion swimsuit’, but if their films were flops, he did not hesitate to say so.

Nor did he confine himself to Hollywood. In 1963 he wrote one of the earliest profiles of The Beatles, describing them as ‘four frenzied Little Lord Fauntleroys who are making £5,000 every week’ with ‘Stone-Age hairstyles’.

As well as film stars, Zec interviewed Muhammad Ali, Prime Ministers Harold Wilson and Margaret Thatcher, and Ronald Reagan. Pictured: Donald Zec with Muhammad Ali in August 1967

Six years later, he joined John Lennon and Yoko Ono in bed on their honeymoon, when the couple invited the world’s Press into their hotel room in Amsterdam to observe them in their ‘peace bed’.

Zec infuriated Lennon by failing to take their peace protest seriously, describing them as ‘two chromium-plated nuts’.

As well as film stars, Zec interviewed Muhammad Ali, Prime Ministers Harold Wilson and Margaret Thatcher, and Ronald Reagan, noting the idea of an ‘ex-star of many films that escape instant recollection’ becoming president was ‘an uneasy thought’.

After having a heart attack in 1972, he left newspapers and wrote several biographies When his wife Frances died in 2006 he took up art, winning the coveted Hugh Casson Prize in 2013.

In later years he seldom talked about his Hollywood days, although he cherished fond memories, particularly of Marilyn.

They truly bonded on that flight to Phoenix in 1956. Shortly after he had joked about her figure, the plane’s engine began belching black smoke. They discussed ‘the unthinkable’ — that the plane might crash — and Zec tried to cheer up Marilyn with the thought that, if it did, her name would be on every front page in the Western world.

‘How would you like to be remembered?’ he asked. The voluptuous actress thought for a while then scribbled: ‘Here lies Marilyn Monroe, 38-23-36’ — a reference to her vital statistics. ‘Pretty sad when you think about it,’ Zec wrote, years later.

He will go down in history as a man who enjoyed unparalleled access to the stars and provided us with an insight into the gaiety and madness of their world.

Source: Read Full Article